BY |

BY |

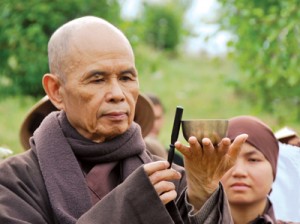

ANDREA MILLER visits Plum Village in France to explore how Thich Nhat Hanh’s community is practicing the five mindfulness trainings. Could these be the basis for a better, kinder world?

I thought there would be a brown-robed monk or nun to pick me up at the train station. Instead, there was a Parisian with closely clipped hair, piercings, and red clam diggers. Together we heaved my suitcase into the van. Then we fumbled in English and French, as she sped full throttle along country roads bathed in the buttery last light of day. We passed an orchard of plum trees, quaintly shuttered stone homes, and tidy rows of grape vines. Yet what cut through my two-plane, three-train jet lag were the fields of sunflowers. Their green stalks and leaves, yellow petals, and brown centers were an image I’d so often seen in literature on Plum Village. I knew I was finally arriving.

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh calls Plum Village “the country of the present moment.” Located in southwestern France, it is the full-time home of some two hundred monas- tics and annually welcomes thousands of retreatants from across the globe. Nuns, monks, lay practitioners—for thirty years they’ve been putting into practice Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings on community and enlightened society. But, day by day, breath by breath, how are they living the teachings? And what, ultimately, are the tools they’re discovering that we could all use to transform our lives, no matter where we are? In making my pilgrimage to Plum Village, these are the questions I wanted to explore.

According to Thich Nhat Hanh, or Thay as he is affectionately called by his students, the essence of his teachings is twofold: one, how you can learn to handle—not cover up—your painful, strong emotions and, two, how you can bring joy and happiness into your life. “You can be happy here and now,” he told me. “You don’t have to look for happiness elsewhere.”

“Mindfulness is a kind of energy that you can produce,” Thay continued. “It’s the energy that helps bring your mind back to your body, so you can live your life more deeply. Mindfulness is the energy that allows you to be aware of what is going on with your body, your feelings, your perceptions—to know what’s going on in you and around you. When you drink tea in mindfulness, you are truly there. You are in touch with the tea; you are truly in the here and the now. But if you are possessed by worry, if you think a lot about the past and the future, then the tea is not truly there. There is no real life. It’s like a dream.”

With mindfulness, Thay said, “you can touch the nature of interbeing. Once you get that insight, discrimination and fear vanish. You know that your happiness is the happiness of other people. Their sorrow is your sorrow. Everything inter-is with everything else.”

On the morning of my first day at Plum Village, it was still dark when I woke to the sound of a young sister ringing a bell, signaling that it was time to get ready for meditation. My dorm was in Hillside, an old farmhouse in New Hamlet, a section of the center that houses nuns, lay single women, and families. All Plum Village retreatants are part of a dharma family who eat and do chores together and have almost daily group discussions. My dharma family was made up of the retreatants staying at Hillside and because our designated chore was washing up after meals, we were known as the Joyful Scrubbers.

The head of my dharma family was Sister Loving-Kindness who had been a nurse for twenty years before ordaining in 1991. “Thay has created Plum Village with the wish that we use the family as a model for relationships,” she told me. “We have elder brothers, elder sisters, younger brothers, younger sisters. The sangha is our support, our home, and a resource for us throughout our practice life. Even if there’s temporary conflict within a small segment of the community, there are others to embrace the two people who may be having difficulties. That’s the benefit of practicing with a community.”

Thay, in his first dharma talk of the week, expanded on the importance of sangha. “It’s possible to practice alone, as individuals,” he said. “But you might lose your practice after a few months because you don’t have a sangha to guide you, to protect you, to support you. That’s why a good practitioner always tries to build a sangha in his town or village. Even a buddha needs a sangha.”

If we are merely individual drops of water, we will evaporate on our way to the ocean. To arrive at the ocean, we must go as a river, as a community. “Go like a river,” said Thay. “Allow the river to embrace you. If you allow the collective energy of the sangha to penetrate into your heart and help hold your suffering, you will suffer less in just a few minutes.”

My interview with Thich Nhat Hanh took place on No Car Day, the day each week that everyone at Plum Village limits their carbon footprint by not driving. In a small, simple room, he was stretched out on a green hammock, drinking oolong from a clear cup and nibbling on candied ginger. Clustered around him were several nuns, and Thay introduced one of them to me as his attendant—a young sister from Indonesia. Then he invited her to sing an Indonesian children’s song, which, if I understood correctly, told a sweet tale about a parrot.

I flicked on my recorder. “Should we start?” I asked.

“Should we start what?” Thay joked. “sitting on a hammock?” It was a gentle reminder that—though my nerves may have been jangled because I felt I was in the presence of a special, important person—Thay was not making a big deal out of himself. Despite being nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King, Jr., despite penning more than one hundred books, despite all his remarkable achievements, Thay wears brown—as do all the monastics in his lineage—because that’s the color the peasants in his Vietnamese homeland have traditionally worn. He is of the people.

A bell rang in the distance. “I’m mindful of the bell,” Thay said. “While I listen to the bell, I don’t think. I concentrate on my breath and on the sound of the bell. When you are mindful of something, you are concentrated on it, and the power of mindful concentration can help you see things as they really are and you discover the nature of interbeing.”

Thay is well known for coining the term “interbeing,” which refers to the interconnectedness of all things. over the years, he has frequently used the image of a flower to explain this teaching. Sunflower, orchid, lotus—if you are mindful and concentrated, you can see that a flower is made of infinite non-flower elements. A flower is made up of not just rain but also the cloud that released the rain. It’s made up of not just soil but also the decomposed plants and animals that enrich the soil. If you remove any of the non-flower elements from the flower, the flower ceases to exist. “So the flower cannot exist alone,” Thay told me. “It has to inter-be with everything else in the cosmos.” The same is true of people. “A human being is made of non-human elements, and if you remove the non-human elements, the human being is no longer there. So a human cannot be by herself alone. She has to inter-be with everything else in the cosmos.”

According to Thich Nhat Hanh, our insight into interbeing is the key to our happiness. “Suffering and happiness inter-are,” he said. “If you understand suffering deeply, you know how to make good use of suffering in order to produce happiness. You know that happiness is made of non-happiness elements, and one of these non-happiness elements is suffering. So suffering has a role in making happiness possible.

“It’s like the lotus and the mud. Without mud, you cannot grow a lotus. Without the mud of suffering, you cannot create happiness. This is why, if you touch the nature of interbeing, you don’t try to run away from suffering anymore. Instead you try to embrace your suffering. You look deeply into it to understand its nature and to learn how to make good use of suffering to produce happiness.”

“If you have gone through a war,” Thay continued, “you have the capacity to appreciate the peace that’s available in the here and now. Many people do not appreciate peace until a war breaks out. But against the background of suffering, you appreciate the peace that’s available.” Likewise, when a person is healthy, he may not appreciate his health. But when he falls sick, he regrets that he did not fully enjoy being healthy and then, when he gets better, he does fully enjoy it. “So suffering and happiness inter-are. They are like left and right, above and below, the mud and the lotus. The understanding of interbeing removes all discrimination—all dualistic thinking—and creates harmony, understanding, and peace. The practice of mindfulness has the purpose of bringing you the insight of interbeing.”

For a concrete method of practicing mindfulness in daily life, Thich Nhat Hanh has crafted the five mindfulness trainings, a modern distillation of the four noble truths and the noble eightfold path. These trainings are (1) reverence for life, (2) true happiness, (3) true love, (4) loving speech and deep listening, and (5) nourishment and healing. “The five mindfulness trainings, are based on the insight of interbeing,” Thay told me. “The insight of interbeing is the ground of better ethics. Then the five trainings are applied ethics that can help reduce suffering and bring more happiness.”

In his book Good Citizens, Thay wrote, “The five mindfulness trainings, are offered without dogma or religion. Everybody can use them as an ethics for their life without becoming Buddhist or becoming part of any tradition or faith. You are just yourself, but you try to make a beautiful life by following these guidelines.” Following the trainings, he wrote, “leads to healing, transformation, and happiness for ourselves and for the world.”

1. Reverence for Life

While at Plum Village, I shared meals with my dharma family under a tree hung with a swing set. There were more than twenty of us, and we didn’t start eating until we were all seated and we’d taken a moment to contemplate our food as a gift from the earth, the sky, farmers, packers, deliverers, and cooks. Then the bell rang and we took our first bites, silently. In order for us to more fully appreciate what was on our plate, there was no talking as we ate. Just the tiny clinking of forks, knives, spoons.

Many people report that at first they find it awkward to eat in silence. But for me, right away it was a relief. Normally I eat with the TV on or with a book in my hand or while talking. Normally, I think this two-things-at-once eating will relax me. Maybe it does a little, but not like eating in silence with my dharma family. In the quiet, I could actually concentrate on the flavors and textures and origins of each mouthful.

Steaming bowls of soup with a clear broth, delicate rice noodles, and chewy mushrooms; bread pudding made from hunks of baguette, mashed bananas, and dark chocolate; pasta salad punctuated with the salty punch of wrinkled black olives. All the food at Plum Village is vegan, reflecting the first mindfulness training, reverence for life. Like many Plum Village practitioners, when I pay attention to what I eat, I don’t want to eat flesh—to eat the suffering of animals.

Sister Jewel, who grew up in Chicago and Nairobi, talked to me about the subtleties of reverence for life. “We inter-are with everything, so if we harm anything we’re harming ourselves,” she said. “If we see that deeply, then we can only practice reverence for life—for all of life.”

At Plum Village, the sangha takes every opportunity to guide people toward reconciliation, peace, and non-violence. This includes hosting retreats for Israelis and Palestinians. To begin, the Israelis and Palestinians separately learn to relax and get in touch with their feelings, their suffering. Then, after a week of experiencing the safety of their own group and the peaceful, loving environment of Plum Village, the Israelis and Palestinians come together for conversation, during which they learn that the other group has also suffered. Previously, according to sister Jewel, “they saw each other as the enemy, but when they really talk and listen to each other, they see that they have a lot in common.” After experiencing a retreat at Plum Village, many Israelis and Palestinians are inspired to work for peace and reconciliation between the two communities.

“We emphasize sangha living because if you have that kind of solid foundation for your life, you will be a peacemaker,” said Sister Jewel. “You will be someone who doesn’t contribute to violence and who protects life. Protecting life—loving life— starts with loving the life in ourselves and not discriminating against our own suffering, our own pain. When we don’t discriminate against the ugly things or the painful things in us, then we also learn not to discriminate against people who we believe are not very kind, not very wholesome. Discrimination is the root of the destruction of life. When we think that something is not okay, when we believe that ‘This is me and that’s not me,’ that discrimination is the root that gives rise to the mind of killing and destruction.” At Plum Village, Sister Jewel concluded, “We get to the root of discrimination through the understanding of interbeing.”

2. True Happiness

“True happiness is not made of fame, power, wealth, or sensual pleasure, but rather of understanding and love,” Thich Nhat Hanh said during our interview. “The capacity to live in the here and the now allows you to recognize that you already have everything you need to be happy. You don’t need to run into the future to look for happiness.”

At Plum Village, none of the monastics has a personal bank account or car or computer. None even has a personal email address. For a monastic, sister Clarity told me, “There is nothing personal—we share everything from our living space to our ideas. We live in rooms with three, four, or five sisters or brothers together. Last winter, I stayed in a room with the largest number of us. There were seven.”

Yet living without the stuff of normal lay life doesn’t create unhappiness. Interviewing sister Clarity in the New Hamlet bookshop, I knew she was happy even before I asked—her smiles were that wide and frequent. But growing up the youngest of seven children, she’s used to living in community and it’s what she values.

“Right now, I’m sharing a room with two other sisters,” Sister Clarity said. “I take care of one sister and she takes care of the other sister and, in turn, that last sister takes care of me.” This, she continued, “is what we call having a second body. We look out for each other, not just in terms of health but also in terms of each other’s well-being and practice. That’s the nice thing about living together. We have a chance to build sisterhood.” I mulled that over. It did sound like a beautiful practice, but I was stuck on the idea of having—at the very least—a personal email account.

Sister Clarity smiled. “It’s nice not having your own email or bank account,” she said. “It’s nice because it’s one less thing to worry about.”

3. True Love

On Lazy Day, a day at Plum Village without a formal schedule, I attended a wedding. It began with walking meditation. The nuns were in front wearing their conical hats and brown robes. Then the couple walked behind them, followed by the guests. Slowly and silently, we wound our way between New Hamlet’s curly roofed bell tower and bamboo grove and all around the large lotus pond before arriving at the Full Moon Meditation Hall. Inside, the couple sat before the altar on their purple zabutons—the bride’s white dress ballooning around her and the groom in his suit and socks.

They had been together for seven years, and the vows they made to each other reflected their intimacy. Ian thanked Raphaelle for introducing him to the Plum Village community and for the multitude of good things she’d brought to his life, saying that without her support he would never have produced his first music album. He promised to water her good seeds by giving her the compliments she well deserved and to do his share of the housework. In her turn, Raphaelle expressed her appreciation for the way Ian made her feel, including when she felt shy or insecure. “You’re a good practitioner,” she told him. “I know you’ll remind me to go back to my breath when I need to calm down, and I will support you when you feel stressed by giving you space to go back to the present moment.”

True love, the third mindfulness training, is about making a deep, long-term commitment to a partner, like the one Ian and Raphaelle share. It is not a heavy-handed law forbidding sex out- side of marriage, nor is it a list of appropriate sexual acts or a judgment regarding sexual orientation. Instead, this training declares that the proper context for sexual relations is a serious commitment made known to one’s family and friends.

While at Plum Village, I spoke with Will Stephens, who for several years has been attending the summer retreat with his family. “Through this practice,” said Stephens, “I’m beginning to learn what true love actually is.” It is not, he explained, “I love you if you meet my needs.” It’s about helping the person you love to be free and happy. “I believe I wouldn’t be with my wife now without this practice. I wouldn’t have had the clarity to see it wasn’t my wife that was the problem. It was my own problem.”

In this post-sixties world, Stephens said, people find it difficult to embrace the training of true love because they like to be able to have sexual relationships without committing long-term. “But in my experience, damage is done to myself and the other person if we have that level of intimacy without commitment. It’s an intrusion into that person’s and my own psyche.”

“I had the experience of sexual relations outside of my marriage,” Stephens admitted, “and that caused a lot of pain to myself, my wife, and the other person.” It’s important to remember that sexual desire is not love, and sometimes cravings for sex actually stem from a deeper need to connect or to validate the self. “For me,” said Stephens, “sexual desire has often been motivated by loneliness, so when my relationship has not been strong, my loneliness has been intense.” But, as the third mindfulness training states, “sexual activity motivated by craving always harms myself as well as others.” It can only ever be a band-aid to loneliness.

Living true love isn’t easy, Stephens acknowledges. “We have to work at it.” The real key is “taking care of the true love, so that the sexual commitment takes care of itself.” These days, he and his wife regularly take time to appreciate each other and to communicate any hurt or difficult emotions that they’re experiencing. Now there’s a lot of love in the relationship; there’s fidelity.

The wedding at Plum Village ended with hugging meditation—the bride and groom in each other’s arms for a long time. Then, outside the meditation hall, they smiled as the guests showered them in flower petals.

4. Loving Speech and Deep Listening

Sister Chan Khong has been working side by side with Thich Nhat Hanh for more than fifty years and is recognized as a major force in the development of Plum Village. She’s also a gifted teacher and, during my retreat, she came to New Hamlet one afternoon to teach a practice called Beginning Anew. It’s a practice that supports the mindfulness training of loving speech and deep listening.

A four-step process, Beginning Anew involves looking deeply and honestly at yourself and improving your relationships through mindful communication. The first step is to express appreciation for the person you’re speaking to, so that you “water his or her good seeds.” That is, you draw attention to their positive qualities and thereby help those qualities grow stronger. Now for the second step: acknowledging any unskillful action you’ve committed in your interactions with the other person. For this, mindfulness can help because it hones your awareness. Next, the third step is to reveal how the other person has hurt you. Here it’s crucial to express yourself in a loving way, without blame—you don’t want to make the other person defensive but rather encourage them to openly explain their behavior. Finally, the fourth step is to share any difficulty that you’re experiencing and request support. After that, the person speaking and the person listening can change roles.

At Plum Village, the monastic community practices the first two steps of Beginning Anew collectively every other week and practices the full four steps in pairs or small groups whenever there’s a need. Sister Chan Khong urges laypeople to practice Beginning Anew at home. It’s even possible to practice Beginning Anew when the person you’re speaking with has never heard of the practice. You can informally go through the steps without the expectation that the other person will reciprocate, and—according to Sister Chan Khong—over time the person’s attitude toward you will shift for the better.

As she said to the group at New Hamlet, “When you look at me, you have a perception of sister Chan Khong, but your perception is only five or ten percent of the reality. The same is true when you look at the person you’ve just fallen in love with or at the person you think you hate.” our perceptions are imperfect, and in order to understand others more, we need to communicate with them.

5. Nourishment and Healing

A mulberry tree by three Buddha statues was arrayed with little pieces of colored paper cut into the shapes of hearts, flowers, candles. From my knapsack, I fished out my own little piece of lime-green paper and wrote on it the names of the family I’d lost so far in my life—grandfathers, grandmother, father, uncle, and aunt. Then I taped the paper to a branch. Today at Plum Village we were having a celebration to honor our ancestors and recognize that we’re a continuation of them. The festivities included a picnic lunch with cake and Chinese dragons flapping their eyelids, wriggling their rumps, and leaping to the quick beat of a drum. What the festivities did not include was alcohol.

While it may be true that I can drink in moderation without any personal damage beyond a hangover, many people cannot. My children, my friends, my co-workers—I can’t see into the double helix of their genes or into the secret corners of their frailties. In short, I can’t know the harm alcohol could cause them in the future. But, by drinking with them and in front of them, I encourage their consumption. So the idea at Plum Village is that if we refrain from intoxicants, it’s not for our own benefit alone.

In my interview with Sister Jewel, she talked to me about the Buddha’s teachings on the four kinds of nutriments, which the fifth mindfulness training addresses. Beyond literal food and drink, there are sense impressions, volition, and consciousness. Sense impressions constitute the food we take in through our eyes and ears—the advertisements, films, books, and conversations we consume.

Volition, on the other hand, is what motivates us in our life; it’s our aspiration. “If you want to become famous or make a lot of money, that wish is a kind of food,” sister Jewel explained. “It gives you energy to stay up late and sacrifice, but you can also have the motivation to relieve suffering, and that can also give you a lot of energy.”

Finally, consciousness, the final nutriment, is what we “eat” all the time. According to Sister Jewel, “It comes from our own individual consciousness, our thoughts, our memories, and also the collective consciousness. If we’re around people who have a lot of fear and anger, we’re eating the collective-consciousness food of fear and anger. But if we’re around people who are peaceful, that peace is a kind of food.”

At Plum Village, practitioners try to mindfully consume each of these four kinds of nutriments. In terms of edible foods, said sister Jewel, “We take only as much as we can eat, and we’re grateful that we have something to nourish us to continue our practice.” regarding sense impressions, “We don’t watch TV or listen to the radio or read the newspaper. We might go online to read, but we only take in what we need to know about what’s happening in the world. We don’t constantly consume news because the news is not the only reality. A lot of it is just focused on what’s negative because that’s what sells.” If we consume so much news that we become depressed or apathetic, it doesn’t help the global situation.

At Plum Village, the computers have bells, which occasionally ring to remind the user to breathe in and out. “Mindfulness bells are a kind of sense food that remind us to take care of ourselves and to not just be in the stream of our thinking the whole day,” Sister Jewel explained. “Our thoughts are sometimes not such healthy food, so to stop the stream of thinking and get in touch with what’s right here and now is nourishing. If we’re attentive, we can hear the wind in the trees and the birds singing. There are so many things to be nourished by if we are aware.“ The collective consciousness food at Plum Village is very healthy, because there are two hundred monastics who are practicing mindfulness all day long, all year-round. Plus, this week there are a thou- sand people here, and when you have a thousand people doing walking meditation together and eating mindfully together in dharma families, it’s very powerful. It’s very healing.”

“The Five Mindfulness Trainings are not laws or commandments,” said Sister Peace, a nun who worked for the mayor of Washington, D.C., before ordaining. Some people decide not to take the trainings because they feel they’d have to do them just right. “Well, who of us can do anything perfectly?” Sister Peace asked. “The five mindfulness trainings are a direction in which we go. It’s like the North Star is over there, so I’m going to go in that direction. And the farther I walk in that direction and transform, the clearer the path becomes.

“We can take many paths, but the essence—the summit—is mindfulness, truth, concentration, insight. Some people may follow the trainings much more strictly and some may just follow them in certain aspects. The key is to do whatever you do with awareness and mindfulness, because the more you become aware of what, for instance, eating meat or drinking wine does to you and your body, the more you can make an informed decision about whether you want to continue.”

On my last evening at Plum Village, a ceremony for the five mindfulness trainings took place at the Full Moon Meditation Hall. In the center of the hall, facing the altar decked in fruit and flowers, sat the people who were taking the trainings, and I joined them there on a purple zabuton, even though I’d already taken the trainings the year before. Sister Peace is right that none of us can ever do anything perfectly, but breath by breath, moment by moment, we all have the capacity to live the trainings a little more fully. They are aspirations we can always renew.

Renewed, I filed out of the meditation hall with my dharma family. Then, as I was on my way back to Hillside for the last time, I realized I wasn’t wearing my watch anymore—a watch with a face that said, in Thay’s calligraphic script, It’s in the middle and now at twelve, three, six, and nine o’clock. It’s now.It’s now It’s now… always. I traced my steps back but couldn’t find the watch and, with the sun going down, I felt sad because that watch was a little piece of Plum Village that I’d no longer be carrying home with me. Then I thought of Thay and my interview with him.

“Plum Village is not so much a place that is situated in time or space,” he’d told me. “You can have it anywhere at any time. If you come to Plum Village and you don’t know how to be in the present moment, it is not the country of the present moment. But if you are in America, or in Asia, and if you are in the present moment, you are in Plum Village. When you fly back to America, you can have Plum Village on the plane. You don’t have to look for the future; you do not need to be caught in the past. If you know how to spend time with joy and peace, you are in Plum Village. You are in the country of the present moment.”

Join the conversation