New York Post, May 18th 1966

By James A. Wechsler

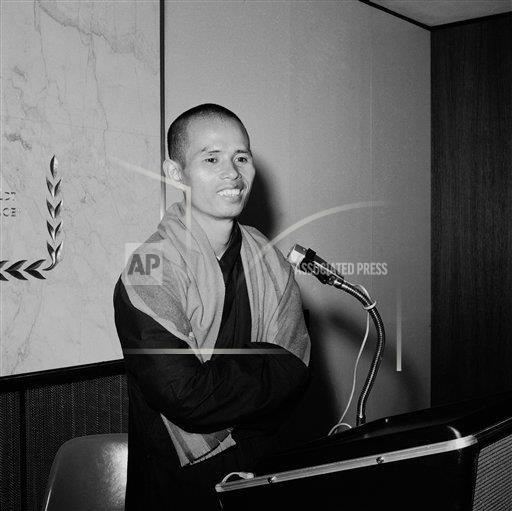

He is a tiny, slender, robed figure; his eyes are alternately sad and animated; his tones are modest and moving. In the American vernacular, there is probably a price on his head in Gen. Ky’s Saigon at this moment. But the message he has brought may contain the last hope for even limited salvation in the dead-end turmoil now confronting us in South Vietnam.

He is Thich Nhat Hanh, a 40-year-old Buddhist monk who is also an editor, philosopher and poet. He seized the chance to journey to the U.S. in response to a speaking invitation from Cornell University; he is making other appearances here under the auspices of the International Committee of Conscience on Vietnam, and its U.S. unit, the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

He was accompanied by Alfred Hassler of the committee when I saw him, but he required no translator. Perhaps more important, he spoke in the international language of the scholar who finds himself thrust into the drama of history, crying not for peace at any price but for an end to madness.

In South Vietnam he is the head of a non-governmental agency called Youth for Social Service; in that role, he has spent many long hours in Vietnamese villages “among peasants who trust us because we are not regarded as a political tool.”

It is, he says, their plea that he bears – an appeal for the chance to live. He sees no prospect that their dream can be fulfilled as long as the U.S. keeps Gen. Ky in power.

Thich Nhat Hanh is devoutly anti-communist as well as anti-Ky, and he speaks for multitudes of his own and other faiths.

If the Vietnamese peasants could vote freely, he asserts, possibly 10 per cent would support the Saigon regime, another 10 per cent might vote Viet Cong – “and at least 80 per cent would vote for a government that would get rid of both” and pave the way for a settlement.

“For the peasant life has been reduced to mere existence or worse,” he says.

“When he is asked about ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy,’ he will answer very simply that what he wants is the chance to build a life for himself – and he will ask ‘what is the use of freedom and democracy?’ if you are not alive.”

In Thich Nhat Hanh’s recital the U.S. role emerges as a tragedy of errors.

On the night of the recent Viet Cong terrorist attack at the Saigon airport, he was in a village half a mile away working with a Youth Service group. U.S. planes reacting wildly, began bombing the area; he narrowly escaped death.

He sees the episode as symbolic; “the innocent peasant” is too often the victim when our planes are hunting the elusive Cong.

To claims of U.S. military successes in the field, he offers the wry footnote:

“They are killing more defenceless peasants than Viet Cong – and each day the war goes on, these actions create more Communists.”

This dedicated man is hardly a stranger in America. In 1961 he studied philosophy at Princeton; in 1963 he was teaching at Columbia when Thich Tri Quang summoned him to return to direct the cultural activities of the Buddhist church. Thereafter he became the head of a publishing house and editor of a magazine called “Thein My” – meaning “the good and the beautiful,” and also the name of a monk who immolated himself in protest against the Diem oppression.

He has come here with no simple answer to his country’s agony. He does not advocate any overnight American withdrawal, but believes there can be no tolerable ending if the U.S. escalates the war in an effort to salvage Ky.

The immediate American goal, he believes, should be the creation of a broad, representative transition government as a prelude to elections conducted under international supervision.

Would the Viet Cong and Hanoi’s leaders reconcile themselves to such a course?

“Once there was a government that was independent, truly nationalist and not committed to the West, and the people could see the possibility of peace, the Viet Cong could not continue to make any progress,” he insists.

A major American fallacy, he adds, is a continuance of the earlier French folly – the belief that only Vietnam’s Catholic bloc could be regarded as authentically anti-Communist.

Others have said and written some of these things, and their voices have stirred no response in Washington. Listening to this frail, earnest figure, one wondered whether the Sate Dept. would permit President Johnson direct exposure to him.

Born in central Vietnam, Thich Nhat Hanh entered a monastery early in life. Then he studied at Saigon University and the Buddhist Institute; he had prepared himself for the life of the spirit and the intellect. But his country’s ordeal plunged him into worldly affairs, and now he is a marked man.

“I can say all these things in New York City, and I must tell the truth,” he remarks, “but when I return home and I assure you I do not seek asylum here, such words will be called a crime.” It is a crime punishable by death if Gen. Ky is still around. Thich Nhat Hanh’s visa expires on June 12.

Join the conversation