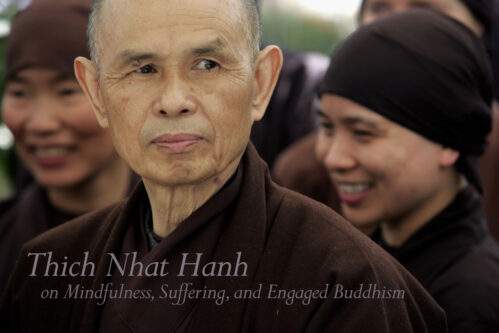

THICH NHAT HANH, CHERI MAPLES AND LARRY WARD —

Zen master and poet Thich Nhat Hanh was forcibly exiled from his native country of Vietnam more than 40 years ago. We visited the Buddhist monk at a Christian conference center in a lakeside setting of rural Wisconsin. Here, Thich Nhat Hanh offers stark, gentle wisdom for living in a world of anger and violence. He discusses the concepts of “engaged Buddhism,” “being peace,” and “mindfulness.”

Listen at http://www.onbeing.org

The interview took place in 2003, and was aired again on Krista Tippett’s show in on 4 June, 2009 and in 2013.

TRANSCRIPT:

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. The venerable Thich Nhat Hanh offers stark, gentle wisdom for living in a world of anger and violence.We’ll speak with him this hour and with others who make use of his teachings in surprising settings. We’ll explore the spiritual discipline of mindfulness, tangibly affecting suffering in the world by facing it in oneself and others head-on.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today,

“Brother Thay: A Radio Pilgrimage” with Zen master and poet Thich Nhat Hanh.

Thich Nhat Hanh is one of the most revered and beloved spiritual thinkers of our time. He first came to the world’s attention in the 1960s during the war in his native Vietnam. He forsook monastic isolation to care for the victims of that war and to work for reconciliation among all the warring parties. He called this “engaged Buddhism.” Martin Luther King nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize, and he led the Buddhist delegation to the 1969 Paris Peace Talks.

Thich Nhat Hanh was expelled from post-war Vietnam because he had refused to take sides even as he worked for peace. He settled in

exile in France. There he founded Plum Village, a Buddhist community or sangha, that has spawned communities of practice and service

around the world. In recent years, his counsel has been sought by CEOs at the World Economic Summit, Harvard Medical School

faculty, even members of the United States Congress.

In our time, people of many faiths are interested in the Buddhist notion of mindfulness. It is a set of disciplines for living fully in the

present moment in a spirit of compassion towards oneself and others. It is a spiritual practice for many with no religious faith at all.

In a sunlit auditorium, about 500 people on retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh prepare for his morning meditation. As the assembly gathers,

Sister Chan Khong, a senior monastic with Thich Nhat Hanh’s community and one of his oldest and closest friends, opens the morning

session.

[Excerpt from opening service]

MS. TIPPETT: Thich Nhat Hanh and members of his Plum Village community have come to a Christian conference center in a lakeside

setting of rural Wisconsin. His students call him “Thay,” the Vietnamese word for teacher. He speaks to the conflict and bewilderment of

contemporary life directly, it seems, having developed his practices through years of chaos and bloodshed. He wrote his classic book,

The Miracle of Mindfulness, as a manual for young nuns and monks who were facing death every day in war-torn Vietnam.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s teaching is practical in application and lyrical in expression. It begins with following one’s breath as a way to plant

oneself firmly in the moment. Thich Nhat Hanh’s counterintuitive message is this: Even the most painful and violent experiences of life

demand our full attention. When we are attentive to our own suffering, he insists, we will know that of others. That knowledge can help

break cycles of suffering and violence in the world around us.

As you listen to my conversation with Thich Nhat Hanh, you may find his Vietnamese-French accent difficult to follow at first. I found

myself leaning in close.

BROTHER THICH NHAT HANH: Mindfulness is a part of living. When you are mindful, you are fully alive, you are fully present. You can get in touch with the wonders of life that can nourish you and heal you. And you are stronger, you are more solid in order to handle the suffering inside of you and around you. When you are mindful, you can recognize, embrace and handle the pain, the sorrow in you and around you to bring you relief. And if you continue with concentration and insight, you’ll be able to transform the suffering inside and help transform the suffering around you.

MS. TIPPETT: And, you know, this word “miracle,” on the surface, is quite intriguing when what you’re describing is so organic. I mean,

it’s getting in touch with your breath, first of all. Does that word or does this phrase “the miracle of mindfulness,” does that come out of

your Buddhist training or was that a phrase that came to you?

BROTHER THAY: It is in my heart when I use it because when you breathe in, your mind comes back to your body, and then you become fully aware that you’re alive, that you are a miracle and everything you touch could be a miracle — the orange in your hand, the blue sky, the face of a child. Everything become a wonder. And, in fact, they are wonders of life that are available in the here and the now. And you need to breathe mindfully in and out in order to be fully present and to get in touch with all these things. And that is a miracle because you understand the nature of the suffering, you know that all of suffering, that suffering play in life, and you are not trying to run away from suffering anymore, and you know how to make use of suffering in order to build peace and happiness.

It’s like growing lotus flowers. You cannot grow lotus flowers on marble. You have to grow them on the mud. Without mud, you cannot

have a lotus flower. Without suffering, you have no ways in order to learn how to be understanding and compassionate. That’s why my

definition of the kingdom of God is not a place where suffering is not, where there is no suffering…

MS. TIPPETT: The kingdom of God?

BROTHER THAY: Yeah, because I could not like to go to a place where there is no suffering. I could not like to send my children to a

place where there is no suffering because, in such a place, they have no way to learn how to be understanding and compassionate. And

the kingdom of God is a place where there is understanding and compassion, and, therefore, suffering should exist.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s quite different from some religious perspectives which would say that the kingdom of God is a place where we’ve

transcended suffering or moved beyond it.

BROTHER THAY: Yes. And suffering and happiness, they are both organic, like a flower and garbage. If the flower is on her way to

become a piece of garbage, the garbage can be on her way to becoming a flower. That is why you are not afraid of garbage. I think we

have suffered a lot during the 20th century. We have created a lot of garbage. There was a lot of violence and hatred and separation. And

we have not handled — we don’t know how to handle the garbage that we have created. And then we would have a sense to create a new

century for peace. That is why now is very important for us to learn how to transform the garbage we have created into flowers.

MS. TIPPETT: Vietnamese Zen master and poet Thich Nhat Hanh. He’s known for his concept of “being peace,” assuming a

compassionate, peaceful presence with tangible effect on the world.

MS. TIPPETT: I look at the violence that marked the world in the period when you were a young monk. There was the Cold War. There

was a certain kind of violence and hostility. A lot of that has changed, has gone away, a lot of the terrible threats and the sources of the

worst fighting. And now in its place we have new kinds of wars and new kinds of enemies. I’d be really interested in, as you look at this

period of your lifetime, is there any qualitative difference between the violence that we have now and the violence that we had then? Is

there anything like progress happening, or is it the same pattern that repeats itself?

BROTHER THAY: Yeah, you are right. It’s the same pattern that repeats itself.

MS. TIPPETT: And does that make you despair?

BROTHER THAY: No, because I notice that our people who are capable of understanding that we have enough enlightenment and if only they come together and offer their light and show us new way, there is a chance for transformation and healing.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, in a retreat like this, you’ve gathered around you hundreds of people who are offering themselves up as

individuals to this kind of training and mindfulness. And you’re not just talking about peace here, there’s a sense of peace. But then the

cynical question would be: Can these individuals make a difference? You know, it seems like we live in an age of collective violence,

collective terror and collective acts of retribution. How do you see the effect of this work that you do?

BROTHER THAY: Well, peace always begins with yourself as an individual, and, as an individual, you might help building a community

of peace. That’s what we try to do. And when the community of a few hundred people knows the practice of peace and brotherhood, and

then you can become the refuge for many others who come to you and profit from the practice of peace and brotherhood. And then they

will join you, and the community get larger and larger all the time. And the practice of peace and brotherhood will be offered to many other people. That is what is going on.

MS. TIPPETT: And you experienced that to be?

BROTHER THAY: Yes, because when I came to the West, I was all alone, and I was aware that I had to build a community. And there was no Buddhists at all at that time. So I work with numerous people, and I suggest the practice of mindful breathing, mindful walking, mindful sitting. And slowly it built a community practice. We even have communities in the Middle East consisting of Israelis and

Palestinians.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I know that you’re bringing Israelis and Palestinians together at Plum Village.

BROTHER THAY: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Is your teaching any different if you’re speaking to members of Congress or you’re speaking to Hollywood filmmakers or

you’re speaking to law enforcement officers?

BROTHER THAY: The practice would be the same. But you need friends to show us how a certain group of people lead their life or what

kind of suffering and difficulties they encounter in their life, so that we can understand. And after that, only after that, we could offer the

appropriate teaching and practice. That is why we continue to learn every day with our practice and sharing.

MS. TIPPETT: Zen scholar and teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, now in his 80th year. In a collection of diary entries from the 1960s, published

with the title Fragrant Palm Leaves, Thich Nhat Hanh wrote, “If you tarnish your perceptions by holding on to suffering that isn’t really

there, you create even greater misunderstanding. One-sided perceptions like these create our world of suffering. We are like an artist who is frightened by his own drawing of a ghost. Our creations become real to us and even haunt us.”

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “A Radio Pilgrimage with Thich Nhat Hanh.”

We’re exploring the practice of mindfulness in a world of violence at a retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh in eastern Wisconsin. For the first time at such a gathering, more than 50 people who work in the criminal justice system are here, about half of them police officers. A police captain from Madison, Wisconsin, Cheri Maples, helped make this possible. She first encountered Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings in the early ’90s and wondered if she could incorporate such ideas into police work. Thich Nhat Hanh surprised her by insisting that there is such a thing as a fierce bodhisattva. A bodhisattva in Buddhist tradition being a person who has reached enlightenment and chooses to stay on Earth to save others. Now Cheri Maples calls Thich Nhat Hanh Thay or teacher. But on her first retreat with him, as a person who carries a gun for a living, she balked at the most basic principle he espouses. That is, a vow never to kill.

CAPTAIN CHERI MAPLES: Well, as a cop, what started to happen to me there got very interesting because — I don’t know if you attended the five mindfulness trainings, but that was one of the things that happened at my first retreat — and I just assumed, well, I’d listen to this, but ‘I can’t do that, I’m a cop.’ You know, I mean, ‘I might be in a position where I have to kill somebody at some point. I can’t think about taking these.’ And Sister Chan Khong, who is one of the — probably the senior monastic here, was at that retreat, and she pulled me aside and she had this very wonderful conversation with me, the essence of it being, ‘Who else would we want to carry a gun except somebody who will do it mindfully? Of course, you can take these trainings.’

And what happened to me is my heart started to soften and kind of break open for the first time. I had gotten very mechanical about how

I was doing my job. I had no idea that I had shut down that way. And I came home and, especially that first week when it was so new

and everything felt so fresh, I started to understand that, in a very, very deep level, that it’s possible to bring this into your work as a cop

because, as my energy started to change, the energy that I brought back from other people started to change, even including the people

that I had to arrest and take to jail.

But probably the first example of that was I was on a domestic violence call, and it was one of these calls where I would have just

arrested the guy. I would have just, ‘Hey, enough’s enough,’ you know? This was a scenario where breaking up is hard to do, and there

was a little girl, and they were exchanging custody. And he was kind of holding the little girl hostage, not wanting to give her back to

Mom. And there had been no violence that had taken place, but both Mom and the little girl were very scared and intimidated. And

ordinarily I would have said, ‘That’s it,’ slapped the handcuffs on him, taken him to jail. But something stopped me, and it was I had just

come out of this retreat. And I got the little girl, got him to give me the little girl, took care of her, got her and her mom set, told them just to leave, went back. And I just talked to this guy from my heart, and, within five minutes, I mean, I’ve got this big gun belt on. I’m about 5’3″. Right? And this guy’s like 6’6″. And he’s bawling, you know. And I’m holding this guy with this big gun belt on and everything.

And he was just in incredible pain, and that’s what I started realizing we deal with is misplaced anger because people are in incredible

pain.

So I ran into him three days later in a little store on Willy Street, where I lived at the time. And this guy comes, he sees me off-duty, he

picks me up, gives me this big bear hug and said, ‘You saved my life that night. Thank you.’ And so when you have experiences like that, and you start to realize, ‘Well, what am I doing different here?’ I mean, really, it’s about softening your heart. When you’re a police

officer and you do this work, you need to find a way to be able to maintain both the compassionate bodhisattva within you and the fierce

bodhisattva and know when each is called for and how to combine the two. And once you start down this path, it’s possible to learn that.

MS. TIPPETT: Did you have a hand in making this retreat happen? Is that right?

CAPT.MAPLES: When I decided to take my practice further — in about 2000, I really got much more committed, and then I decided I

wanted to become a member of the order, a core member of the order. And then I went out to Plum Village last year.

MS. TIPPETT: In France?

CAPT.MAPLES: In France for three weeks, which was probably one of the most wonderful three weeks of my entire life. You know, as a

police officer, you’re so often a victim and so often an oppressor. You know, you really have to come to grips with both of those. And I

wrote a letter to Thay, because when you want to receive the mindfulness trainings, that’s one of the requirements. He got my letter,

which talked a lot about sort of where I’m at with all this, and the next day gave this two-hour Dharma talk on the different faces of love

and why it’s possible to be a bodhisattva and carry a gun. It was just unbelievable to me.

I just started having this image while I was out there of my co-workers, other police officers, holding hands and making — doing

walking meditation together and making peaceful steps on the Earth together. And I mentioned it during a working meditation with one

of the people. She said, `You know, you can make that happen.’ So by the end of the retreat, I got on the stage with Thay, and I asked

him if he would do a retreat for police officers, and he said yes. And this is it.

MS. TIPPETT: And tell me what you are hearing or experiencing of the effect this is having on your colleagues.

CAPT.MAPLES: Well, at first, it was kind of a mini revolt because they really thought — it’s a very, very big thing having to face the

possibility of having to kill somebody that you could face every day. They wanted to talk about that with each other. They wanted to talk

about, `Why are we so critical of each other? Why is there so much stress in our workplaces? How can we apply some of these

concepts?’ And they also sometimes, if you’ve never been exposed to Thich Nhat Hanh and — I can translate the language for them, but

some of them hear you can never, never fight violence with violence, and they’re saying to me, `Well, what the hell am I supposed to do

when somebody’s beating the crap out of somebody? Am I supposed to stand there and watch them? ‘ So some of it is literally a

translation thing. But to watch them getting the sort of understanding and exposure that I had early on, just to see that there’s some

richness and nourishment here. And what we talked about yesterday is my first Zen activity as a little girl was baseball because that was

the first activity that I ever performed where I was so absorbed in it my total focus and concentration was there and nothing else was

present.

MS. TIPPETT: And that’s a definition of Zen.

CAPT.MAPLES: That’s my definition of Zen. And so you have to, as a practitioner, find the ways to practice that resonate with you. And

if you are faithful to your practice, your practice will be faithful to you.

Police officers, as you can imagine, the major problem is we deal with being hypervigilant all the time, so we’re off the scale up here.

You know, you’re looking around you all the time wondering where that next problem is coming from. And if you don’t have a way to

come back down and find some ways to take care of yourself, you’re going to find ways to stay up there because it feels good in an odd

sort of way, in dysfunctional ways.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I asked Thay, `How is your teaching different when you’re speaking to these different kinds of groups?’ And

his answer was so interesting, that he has to come to understand the particular suffering of that group of people.

CAPT.MAPLES: It’s a special form, and Thay has really taken so much time to understand it. And where our suffering comes from is

really two places. One, we deal with the 5 percent of the worst part of society, so you start — you know, you don’t want your kids

exposed to that. You don’t want your partner exposed to that. It’s got to go somewhere. You don’t know who to talk to about it, but it

starts to affect the way you see people. That’s one thing. And the accumulated stress of, you know, if you’re a young officer and you go

to your first accident scene where somebody’s head has been rolled over, you go to your first — you go to a homicide scene and you see

very grisly details, you go to lots of different things that — one incident may not cause it, but the accumulated sort of stuff post-traumatic stress is made from, and you start shutting down and you don’t realize it. So you need tools to keep your heart open and soft.

MS. TIPPETT: Cheri Maples is now an assistant attorney general for the Wisconsin Department of Justice.

This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more conversation with Thich Nhat Hanh on the implications of his teaching for the war on terror.

This exploration continues at speakingoffaith.org. This week delve into Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings and poetry. Use the Particulars

section as a guide and download this show to your desktop or subscribe to our free weekly podcast and listen on demand at any time and

any place. While exploring, read my journal on this week’s topic and sign up for our free e-mail newsletter. All this and more at

speakingoffaith.org. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista

Tippett. Today, “A Radio Pilgrimage” to reflect on living in a world of violence with Vietnamese Zen master and poet Thich Nhat Hanh.

During the Vietnam War, Thich Nhat Hanh’s ideas and examples influenced the Catholic monk and author Thomas Merton and the civil

rights leader Martin Luther King. Millions of people since have read his classic manual of meditation, The Miracle of Mindfulness. He

writes, “Meditation is not evasion. It is a serene encounter with reality. The person who practices mindfulness should be no less awake

than the driver of a car. Be as awake as a person walking on high stilts — any misstep could cause the walker to fall. Be like a lion going

forward with slow, gentle and firm steps. Only with this kind of vigilance can you realize total awakening.”

At this retreat led by Thich Nhat Hanh on Green Lake in Wisconsin, day begins with walking meditation at dawn. Hundreds of people

step slowly, conscious of their breathing and every movement of their bodies. As a group, they wind around the lake and among the

trees. Thich Nhat Hanh walks in front holding the hand of a small child. In a manual he’s written about walking meditation, one of his

signature practices, he advises practitioners to take the hand of a child. Though this might alter the solemnity of meditation, he writes,

“she will receive your concentration and stability, and you will receive her freshness and innocence.”

The walkers maintain silence. This noble silence, as they call it, is also held at all meals. Periodically, the sound of a bell stills the

cafeteria dining room. This is a reminder to breathe, to eat only what is required to nourish the body, and to be present in the moment.

Attention to the present moment is the heart of Thich Nhat Hanh’s passion. This is a way of life rather than a system of belief. In fact, he

insists that attentive living will constantly cause us to question our own reactions and convictions. We suffer because of wrong

perceptions of ourselves and others, which is why communication is so difficult and so important. Forgiveness, he says, comes from

looking deeply and understanding. Violence, whether it be in our families or in the larger world, can stop with us. Living this way, he

says, we become fresh, solid and free. Here’s more of my conversation with Thich Nhat Hanh.

MS. TIPPETT: Some of the things you’ve said about the war on terror, you used the word “forgiveness” right away, and I don’t think that

was a word that was anywhere in our public discourse in this country. But I also heard you this morning, when you were speaking with

the group, talking about the responsibility of everyone also for policies, global policies. Say some more about that, about what role

individuals have to play even in something like the war on terror, from your perspective.

BROTHER THAY: Well, the individual has to wake up to the fact that violence cannot end violence, that only understanding and

compassion can neutralize violence because, with the practice of loving speech and compassionate listening, you can begin to understand people and help people to remove the wrong perceptions in them because these wrong perceptions are at the foundation of their anger, their fear, their violence, their hate. And listen deeply. You might be able to remove the wrong perception you have within yourself concerning you and concerning them. So the basic practice in order to remove terrorism and war is the practice of removing wrong perceptions, and that cannot be done with the bombs and the guns. And it is very important that our political leaders realize that and apply the techniques of communication.

We live in a time when we have a very sophisticated means for communication, but communication has become very difficult between

individuals and groups of people. A father cannot talk to a son, mother cannot talk to a daughter, and maybe husband cannot talk to a

wife. And Israelis cannot talk to Palestinians, and Hindus cannot talk to Muslims. And that is why we have war, we have violence. That

is why restoring communication is the basic work for peace, and our political and our spiritual leaders have to focus all their energy on

this matter.

MS. TIPPETT: But I think some would say —people in positions of power would say that they simply can’t wait for that communication

to happen or for that change to take place, that they also have to act now.

BROTHER THAY: If they cannot communicate with themselves, if they cannot communicate with members of their family, if they cannot communicate with people in their own country, they have no understanding that will serve as a base for right action, and they will make a lot of mistakes.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m wondering if, you know, by way of bringing this back to you and the practice and how you know the practice, if you

would read this poem, “For Warmth,” and talk about how you think about anger and how one lives with anger. Being mindful doesn’t

take away all these emotions. Right? These human emotions.

BROTHER THAY: Well, we have to remain human, you know, in order to be able to understand and to be compassionate. You have the

right to be angry, but you don’t have the right not to practice in order to transform your anger. You have the right to make mistakes, but

you don’t have the right to continue making mistakes. You have to learn from the mistakes.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. And would you say something about when you — the occasion on which you wrote this poem also?

BROTHER THAY: I wrote this poem after I hear the news that the city of Ben Tre was bombed, and an African army officer declared that he had to destroy the town in order to save the town. It was so very shocking for us. In fact, there were a number of guerillas who came to the town, and we use anti-aircraft gun to shoot, and, because of that, they bombarded the town and killed so many civilians.

MS. TIPPETT: Was it 1965 or something like that?

BROTHER THAY: Yeah, around that time.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

BROTHER THAY: (Speaking Vietnamese)

MS. TIPPETT: (Translating) “I hold my face between my hands. No, I am not crying. I hold my face between my hands to keep my

loneliness warm, two hands protecting, two hands nourishing, two hands to prevent my soul from leaving me in anger.”

BROTHER THAY: When you notice that anger is coming up in you, you have to practice mindful breathing in order to generate the energy of mindfulness, in order to recognize your anger and embrace it tenderly, so that you can bring relief into you and not to act and to say things that can destroy, that can be destructive. And doing so, you can look deeply into the nature of the anger and know where it has come from. That practice help us to realize that not only Vietnamese civilians and military were victims of the war, but also American men and women who came to Vietnam to kill and to be killed were also victims of the war.

MS. TIPPETT: Vietnamese Zen master and poet Thich Nhat Hanh, whom many people of different faiths consider to be one of the great

spiritual teachers of our time. He gives retreats and delivers speeches around the world. In this country, his personal appearances draw

thousands of people.

MS. TIPPETT: So here’s the question that occurs to me again and again. These root causes are so simple in a way — wrong perception,

poor communication, anger that may have its place in human life but then needs to be acted on mindfully, in your language. Why is it so

hard for human beings — and I think this is as true in a family as it is in global politics — to take these simple things seriously, these

simple aspects of being human?

BROTHER THAY: I don’t think it is difficult. In the many retreats that we offer in Europe, in America, in many other countries, awakening, understanding, compassion and reconciliation can take place after a few days of practice. People need an opportunity so that the seed of compassion, understanding in them to be watered, and that is why we are not discouraged. We know that if there are more people joining in the work of offering that opportunity, then there will be a collective awakening.

MS. TIPPETT: I look at you and I also see that you view the world through the eyes of compassion, which is another term you use, and that I see the weight of that on you. It is also a burden to look at the world straight and to see suffering and to see the sources of suffering wherever you look.

BROTHER THAY: When you have compassion in your heart, you suffer much less, and you are in a situation to be and to do something to help others to suffer less. This is true. So to practice in such a way that brings compassion into your heart is very important. A person without compassion cannot be a happy person. And compassion is something that is possible only when you have understanding. Understanding brings compassion. Understanding is compassion itself. When you understand the difficulties, the suffering, the despair of the other person, you don’t hate him, you don’t hate her anymore.

MS. TIPPETT: What would compassion look like towards a terrorist, let’s say?

BROTHER THAY: The terrorists, they are victims of their wrong perceptions. They have wrong perceptions on themselves, and they have wrong perceptions of us. So the practice of communication, peaceful communication, can help them to remove their wrong perceptions on them and on us and the wrong perceptions we have on us and on them. This is the basic practice. This is the principle. And I hope that our political leaders understand this and take action right away to help us. And we, as citizens, we have to voice our concern very strongly because we should support our political leaders because we have help elect them. We should not leave everything to them. We should live out daily in such a way that we could have the time and energy in order to bring our light, our support to our political leaders.

We should not hate our leaders. We should not be angry at our leaders. We should only support them and help them to see right in order to act right.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to finish because I know I’ve taken a lot of your time. I want to ask you, this is from Fragrant Palm Leaves, which I know is a journal you wrote in the 1960s, but this is about Zen: “Zen is not merely a system of thought. Zen infuses our whole being with the most pressing question we have.” What are your pressing questions at this point in your life?

BROTHER THAY: Pressing questions?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. What are the questions you work through in your practice just personally, I wonder.

BROTHER THAY: I do not have any question right now. My practice is to live in the here and the now. And it is a great happiness for you to be able to live and to do what you like to live and to do. My practice is centered in the present moment. I know that if you know how to handle the present moment right, with our best, and then that is about everything you can do for the future. That is why I’m at peace with myself. That’s my practice every day, and that is very nourishing.

MS. TIPPETT: And I wonder, living that way and practicing that way, does forgiveness become instinctive? Does there become a point where you no longer react with anger but immediately become compassionate and forgiving?

BROTHER THAY: When you practice looking at people with the eyes of compassion, that kind of practice will become your habit. And you are capable of looking at the people in such a way that you can see the suffering, the difficulties. And if you can see, then compassion will naturally flow from your heart. It’s for your sake, and that is for their sake also. In The Lotus Sutra, there is a wonderful, five-word sentence. “Looking at living beings with the eyes of compassion,” and that brings you happiness, that brings relief into the world, and this practice can be done by every one of us.

MS. TIPPETT: Zen master and poet Thich Nhat Hanh.

I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, we’re on a radio pilgrimage with Thich Nhat Hanh.

Larry Ward is one of 500 people in attendance at this retreat. He’s a former management consultant to Fortune 500 companies and an

ordained Baptist minister. Now he and his wife lead a meditation center in Asheville, North Carolina. I asked Larry Ward to tell me how

he first came into contact with Thich Nhat Hanh. Like others here, he uses the term Thay, which is Vietnamese for teacher.

MR. LARRY WARD: I was introduced to Thay through my wife, who was then my fiancée. A number of years ago her first husband

passed away in a tragic accident, and as we began to get closer some years later, she told me that there’s this monk coming to the United

States, and he came every two years. And it was one of the fundamental things that helped her heal her grief after her husband passed

away and that that experience meant so much to her she’d like for me to go with her to a retreat to meet this teacher.

MS. TIPPETT: So tell me what it was about the teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh, this particular way that he’s developed Vietnamese Zen,

that affected you, that has been important to you.

MR.WARD: OK. Two things that particularly were inspiring to me of Thay’s teachings: One was his ability to translate Buddhist practice

as human spirituality, and secondly, to do that with great heart. And I think one of the contributions of the Vietnamese aspect of Thay is

the great heart, the sense of poetry, metaphor that he brings with depth, intellectual clarity and scholarship. And so that combination is

very appealing.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if you can think of, say, a situation where you think you might have done something differently than you would

have before, a concrete way in which it changed your action or reaction in some way.

MR.WARD: When my mother passed away about seven years ago, I was actually on vacation with my wife and some friends in Costa

Rica. And I was in a small village that only had two telephones, one private, one public. The public one did not work. This was around

Christmastime. So when I was finally able to get a phone and call, I found out my mother died. And so I went. It took three days to get

back to Cleveland where she was, and by that time she was already buried. And my father was overwhelmed with grief, and he was so

overwhelmed with grief that after the burial, he went home and he shut the door and he wouldn’t let any of the children in the house.

So I started sending him flowers and love letters over six months’ time. And I would go visit, and I’d sit outside the house and bring my flowers and put them on the porch. And this is after flying from Idaho or wherever I was. And I knew he was in there, and I’d leave them.

And then I’d go on and visit my sister, you know, etc., etc. And finally, he opened the door, which was to me opening the door to

himself. And so now we’re in a totally different environment and a different situation, and I’m certain that without the practice that is not how I would have responded to an experience, quote, unquote, of “rejection.”

You know, I grew up in Cleveland, Ohio. If I’d have been operating out of that mindset of my youth, I would’ve just said, you know,

forget you. And, instead, I was able to understand what was happening to my father. I could see and feel his suffering, his tremendous

heartbreak. I knew that he didn’t have any training in dealing with emotion. None. And I knew that, in my family, my mother was the

emotional intelligence, and that when she passed away, he had no skills, no capacity to handle the huge ocean of grief he found himself

in. So my practice was to communicate to him that I was there for him, that I supported him and that I loved him, but my practice also

was to hold compassion for him and myself and my family so that we could all go through our grieving process peacefully and at our

own pace.

MS. TIPPETT: When I interviewed Thay yesterday, I said to him that I’ve noticed that he’s doing retreats for different kinds of groups of

people, you know, law enforcement officers, members of Congress, people of color. You know, on the surface, I don’t know, you know, I

wasn’t quite sure what that was about. And then when I asked him, you know, “Is your teaching different? ” And he said, “You know,

what I’m trying to do, what I have to do every time is understand the particular suffering of these people who’ve lived with a certain kind

of identity.” And I’d like to ask you as an African-American man, you know, do you feel that this Vietnamese Buddhist monk can speak

to your suffering or your identity? How do you experience the coming together of his culture and yours?

MR.WARD: From a distance many years ago, I heard Martin Luther King mention that a monk had asked him to come out against the

Vietnam War and that he was nominating this monk for the Nobel Prize. And I had heard that before my wife introduced me to Thich

Nhat Hanh, and it was only during the middle of the retreat that the dots got connected for me.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, in the early ’90s?

MR.WARD: In the early ’90s. Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: That you realized that that was the monk?

MR.WARD: That was the monk.

MS. TIPPETT: Wow.

MR.WARD: And unequivocally, yes. Thay’s deep practice emerged in the midst of tremendous suffering of the war, and that’s a part to

me of his authenticity is if, as he’s able to be peaceful and graceful and kind — and I know some of the things he experienced in the war

because I also had family members in the war — but for him to be able to be that peaceful and that openhearted and that kind in the

midst of the suffering he experienced without denying the suffering, I think that’s a perfect model, pathway, through the African-

American experience into the full human experience.

MS. TIPPETT: A cynic would say, “Well, he can give these beautiful teachings about ending violence. And then there are these

individuals who come to a retreat like this who are clearly taking this seriously and taking this back to their lives, but they’re just drops in the ocean.”

MR.WARD: That is true. I am a drop in the ocean, but I’m also the ocean. I’m a drop in America, but I’m also America. Every pain, every

confusion, every good and every bad and every ugly of America is in me. And as I’m able to transform myself and heal myself and take

care of myself, I’m very conscious that I’m healing and transforming and taking care of America. Particularly I’m saying this for

American cynics, but this is also true globally. And so as we’re able, however small, however slowly, it’s for real.

MS. TIPPETT: Larry Ward lives in Asheville, North Carolina, where he’s co-director of the Lotus Institute devoted to the teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh.

The Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh makes his home at Plum Village in France.

Share Your Reflections