Thay’s letter to the Bat Nha Monastics, continued.

Blue Cliff Monastery

October 21, 2009

Yesterday, in the Great Harmony Meditation Hall of Blue Cliff Monastery, there was an ordination ceremony for two young people, one who had already graduated from Dental School and the other, from Business School. They are sisters Chan Lan Nghiem (True Adornment of Love) and Chan Manh Nghiem (True Adornment of Beginning, i.e. in Beginner’s Mind). These two sisters had the opportunity to learn the precepts and mindful manners from Thay for a whole week before the ordination date. They have been accepted as permanent residents in the White Crane Hamlet at Blue Cliff Monastery.

When Thay shaved these young sisters’ heads, he prayed for them wholeheartedly that they could keep their beginner’s mind for their entire monastic life. If one is able to keep one’s beginner’s mind, with certainty one will succeed. There are those who practice successfully, and there are those who do not. If the monastics do not know the way to practice, then they can lose their integrity as they receive the respect and offerings from the lay people. Therefore, every time when there is a group of young people being ordained, the first advice that Thay gives them is to be very careful with the respect and offerings from the lay practitioners.

Putting on the monastic robe, we become the symbol of the Three Jewels which are the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. We represent the Sangha Jewel. In the Sangha Jewel, there is the Dharma Jewel and the Buddha Jewel. For this reason, when lay practitioners see a monastic, they want to express this reverence through making offerings and prostrating before that monastic.

How should a newly ordained monk or nun practice when someone comes to prostrate before him or her? We have the tendency to think, “Please do not prostrate before me, because I am just recently ordained, I do not have any merits or virtues for you to show reverence to.” When we refuse like that, this lay practitioner loses an opportunity to express his/her reverence for the Three Jewels. Therefore, instead, we should sit very still, following our breath and contemplating, “This person is expressing his/her reverence to the Three Jewels, not to my ego. I must sit still so that this person may touch the earth. He/he prostrates to the Three Jewels and not to me.” Practicing like so, we will be safe and our humility will be protected. If not, we will be corrupted. We become corrupted because we have the perception that we are the object of the reverence. It is like the national flag – it is only a piece of cloth. In saluting the flag, people are saluting a country, not a piece of cloth. If that piece of cloth thinks that it is the object of the salutation, then it is mistaken.

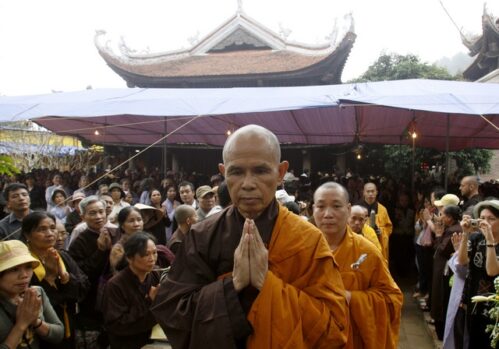

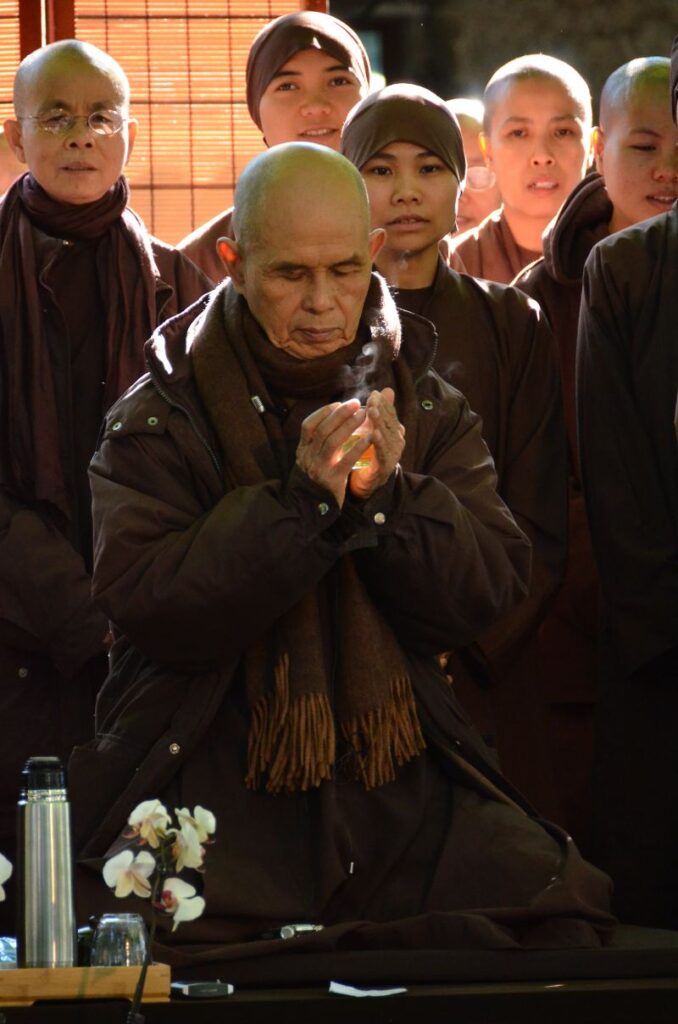

Thay, himself, does not like to let people prostrate or touch the earth before him. But Thay has to practice sitting there so that people may touch the earth. Touching the earth is an important practice for the lay practitioners, therefore, we should sit with mindfulness and represent the Three Jewels. If we can practice like that, the person touching the earth may nourish his/her reverence for the Three Jewels, and in turn, we nourish our humility. If we do not practice, then we become victims of the respect, and our monastic life will be jeopardized.

Your Grandfather Monk, Patriarch Thanh Quy, had great humility. His nature was also disliking people prostrating to him, but because he was a teacher, Grandfather Monk allowed them to do so. When the Venerable Chi Niem built the stupa for Grandfather Monk, Grandfather Monk instructed him to place on the tip of the stupa a statue of the Buddha. Later when people came to touch the earth, Grandfather Monk’s intention was for them to be expressing their reverence towards the Buddha, and not towards Grandfather Monk. Everyone knows about this story at our ancestral temple Tu Hieu. We, teacher and student, must learn this humble attitude from the Patriarch Thanh Quy. This practice of humility will help us maintain forever our sense of who we are. We can see that in both the Northern and Southern traditions, there are monastics who become corrupted because they lack this practice. They see people prostrating to them and think that these people are admiring their egos. Meanwhile, everyone knows that the self (the ego) is the most offensive obstacle. In the Buddhist tradition, the self is only an illusion.

When we touch the earth, we have the opportunity to let go of the illusion of the self. With the five points of our bodies on the ground (two knees, two elbows, and forehead), we open wide upward, our two palms. We contemplate, “Respected World Honored One, respected spiritual and blood ancestors, I have nothing to be proud of. Whatever that I have – my little bit of talent and intelligence – they have all been transmitted to me from you, the Buddha and my ancestors. I am only your continuation.” Looking deeply in this way, we feel that in our being there is a lot of space and freedom, and we can release the complex, (the idea) of superiority. If we have an inferior complex, we also contemplate like that: “Respected World Honored One, respected spiritual and blood ancestors, I have certain weaknesses and shortcomings. They are also not mine, but they have been transmitted to me. As your continuation, I vow to practice to transform these weaknesses in me and to fulfill your expectations.”

A monastic life must be both modest and simple. The ten novice precepts that we receive the day we enter the monastic community are beautiful Dharma precepts. The sixth precept is on not using cosmetics or wearing jewelry, the seventh precept is on not being caught in worldly amusements, and the eighth precept is on not living a life of material luxury. “Aware that a monk or nun who lives with too much comfort or luxury becomes prone to sensual desire and pride, I vow to live my whole life simply, with few desires. I resolve not to sit on luxurious chairs or lie down on luxurious beds, not to wear silk or embroidered fabrics, not to live in luxurious quarters, and not to travel using luxurious means of transport.”

The beauty of a monastic is made of the humble virtue and the simple life. Therefore, upon receiving offerings, the monastics do not keep it for themselves, but turn the offerings to the Sangha, the monastic community. These offerings are only for those who are in real need. The monastic life has to be “insufficient in the three basic needs.” This means that in meeting our needs for food, clothing and shelter; none of these three needs should be met too sufficiently.

For this practice to be correct, we have to lack a little bit. For example, when we eat, we should not eat until we are too full. When we dress, we should not dress too comfortably, let alone too beautifully. When we stay in a place, it should not be too comfortable, let alone too luxurious. With these standards, one can determine who are the true practitioners, and who are not. Putting on the monastic robe, we have the dignity to receive respect and offerings. If we do not practice, we will abuse that reverence and offerings and lose our Dharma body. The Dharma body is the true spiritual life.

Thay is fortunate that even at this age, Thay still feels embarrassed when a lay practitioner makes an offering to Thay. As you may already know, Thay also lives simply like you, and every time someone makes an offering to Thay, Thay never keeps it to himself. In all our monasteries, we have the Understanding and Love Program (a relief program), and we always reduce our consumption in order to share our material resources with those in need – the orphans, the destitute elderly, the poor children without education and proper nutrition, and victims of poverty, diseases and natural disasters. We nourish our compassion and loving kindness through these helping programs. And there are so many monastic and lay brothers and sisters who have been helping us wholeheartedly in this work. This is one of the great happiness of the monastics. It is the practice of the second precept: sharing time, energy and material resources with those in real needs. The essence of our happiness is derived from our deep aspiration and our brotherhood and sisterhood; and not from our consuming. Young people come to us in great numbers because they are able to touch this happiness. By joining our community, they can practice letting go of their attachments and suffering, and they are able to taste the happiness brought about by a deep aspiration and from true brotherhood and sisterhood. Both sisters that ordained yesterday came from rich families. They were well-educated and had more than enough conditions to live a materialistically filled and luxurious life. But they have renounced everything so that they could ordain. Their eyes sparkled when they received the novice precepts. This proved that they have great happiness, and this happiness is made of the substance of deep aspiration and brotherhood and sisterhood.

Thay recognizes that a revolutionist also has an aspiration similar to the aspiration of a monastic. Prince Siddhartha Gautama’s action of leaving his throne to become a monk was also a revolutionary action. We can let go of worldly attachments because we have great aspirations. The revolutionist must also have great aspirations; if not, he/she will not be able to let go of the material life and to follow the path of service of his/her country. And like the monastics, the revolutionary must live a simple life, not weighed down by fame and benefits. A true revolutionary also lives a simple life like a monastic and his/her happiness is similar to that of a monastic’s. This means that the substance of this happiness is a deep aspiration and a sense of comradeship. “Your shirt sleeves torned to the shoulder; and my pants ragged with two patches. Still, we smile; even with our feet, frigid without shoes. Loving each other, we hold each other’s hand” (from a revolutionary song). In this spirit, a police officer is also a revolutionary. The police officer can also live happily with his revolutionary ideal and his comradeship like the monastics.

Of those who received the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings in the United States, there was a Captain in the police force, named Cheri Maples. She practiced very well according to the Plum Village tradition. In the beginning, she received the Five Mindfulness Trainings, then after many years, she received the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings, and in 2008, she received the lamp transmission to be a lay Dharma Teacher. In fact, Cheri Maples had already performed outstandingly her responsibility as a Dharma Teacher over the last ten years. She transmitted the practice to those who had the responsibility of keeping the peace in society – the police officers, the attorneys, the judges, and those in the Department of Corrections.

Cheri Maples had been in the police force for 20 years, and she was in charge of all the hiring, firing, and training of new and current officers. Of those 20 years, Cheri Maples practiced in the Plum Village tradition for 14 years. This practice helped Cheri transform a lot, and it helped her succeed enormously in the training, distributing and assigning the police officers. Because of this great success, she was invited to work in a high position in the Department of Corrections and in the Department of Justice. In these positions, Cheri trained over 1500 people, including police officers, attorneys, judges, and state officials in the techniques she learned from Plum Village. Currently, Cheri is implementing these practices to help those who work in prisons, as well as the prisoners.

In 2003, Cheri organized a retreat in Madison, Wisconsin for over 650 people, mostly police officers and other criminal justice professionals. Thay and the Plum Village Sangha were invited to come lead this retreat. In this retreat, there was no incense offering, chanting or ceremony. There was only the practice of calming and transforming our body and mind, the practice of reviving and nourishing the substance of our deepest aspiration and brotherhood/sisterhood, and the practice of bringing a spiritual dimension into our professional life so that we can be more successful in our profession and have more joy in our daily life. This retreat was very successful. My children, just imagine very stocky and built American police officers doing walking meditation with gentle and free steps, sitting in meditation with calm breaths, listening deeply and speaking lovingly with a stable sitting posture. The life of the police officers and those who work in the Department of Justice is often full of stress and suffering. Do you know that each year in the U.S., there are about 300 police officers who commit suicide with their own guns? This, they refer to as “eating their own guns.” The number of police officers committing suicide with their own guns is twice as many as the number of police officers being shot by gangsters and criminals. The prison guards are so full of stress, because they have to confront frequently the energy of violence in the prison and in themselves. Statistically, after 20 years of serving in this field, most prison guards only have an average life span of 58 years.

Certainly those policemen and guards who came to Bat Nha and caused difficulties to Thay’s Bat Nha children also had a lot of tension and suffering in them. They are government officials and they have to obey the orders from their superiors, and many times, they are forced to do things that they feel torned in their minds and bodies. When Thay’s baby monks wrote the letter to the policemen, you were able to see this, and Thay silently praised you when Thay read that letter. The police officer’s salary is not enough to live by; Thay is aware of that, and a number of police officers have to use their power and position to get more money and, as a result, they gradually lose their aspiration to serve their country.

Cheri Maples said that in 1984, when she joined the police force, her deepest aspiration was to work for peace and to end violence and injustice. That was the substance of aspiration. Cheri wrote in the foreword to one of Thay’s book: “I quickly became intimately familiar, on a nightly basis, with the suffering caused by poverty, racism, social injustice, stealing, sexual abuse, domestic abuse, unmindful consumption, and oppression. I deeply craved peace, but I did not understand that peace began in my own heart. I felt overwhelmed by the suffering that I witnessed, caused by public misunderstanding, and by the politics of my own department. This misplaced anger of others fanned my own impatience and anger. I began to do my job in a mechanical way. I consumed too much alcohol, and I became angry and depressed. As a result, I brought suffering into the relationships with my family and others.”

After being in touch with the Plum Village practice, she learned that she could carry a gun with mindfulness. Cheri began to transform and was able to revive her deep aspiration. In the end, Cheri was able to serve her country and her people very deeply. Cheri’s happiness increased greatly thanks to her practice. When she learned that you had been evicted from Bat Nha and under strict surveillance at Phuoc Hue Temple, she wrote a letter to the President and to the Minister of National Public Security Department of Vietnam to ask them to intervene, so that you may safely return to your practice in the place you were ordained. Cheri sent Thay a copy of that letter.

If Cheri practiced successfully and was able to rekindle her aspiration to serve her country, to find joy in her life of service, due to her diligent spiritual practice. Then is it not true, my children, that our police officers can do the same as well, especially when we know that many of these officers and policemen are from Buddhist families. In the letter sent to the President and the Minister of National Public Security Department, Cheri shared her hope that in the future, there will be retreats for government officers in Vietnam like the one organized in Wisconsin, and that there is a possibility that police officers and other government officials from the United States can come to Vietnam to practice together with the police officers and other government officials in Vietnam. The retreat in Wisconsin was a great success, although it was not an easy retreat. In the beginning, the suffering and prejudices were severe, but they were gradually transformed in the retreat. The theme of the retreat was “Keeping the Peace.” This theme makes Thay remember a children’s song in the North, “Uncle policeman, we love you very much. With the guns on your shoulders, you keep the peace.” The mindfulness practices provided at the retreat had an extremely positive effect on both the police officers and the community. Cheri wrote in her letter: “As a result of Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings, I believe our department was transformed – from being police officers dependent on our authority to being peace officers dependent on our relationships with the people in the community.”

The retreats organized for police officers, for congress people as well as for government officials were held in a non-sectarian spirit. There were no devotional and ceremonial practices as in other retreats, because according to the laws of the Western democratic countries, religion and the state cannot be mixed. Thay and the Sangha respected that principle, so during those retreats, we did not have the intention to convert the retreatants into Buddhists. We only wanted to help these practitioners to transform their suffering and internal difficulties and to rediscover faith in their ideals and their brotherhood/sisterhood.

The studies in our Buddhist Institutes are more theoretical than practical. These practices need to be implemented into the basic, intermediate and high levels of the Buddhist Institutes, so that Buddhism can truly be applicable in daily life. Only with these practices, a practitioner may recover and maintain stably his/her monastic aspiration and not to be caught by fame and profits. This practice is also beneficial to People’s Public Security intermediate schools, People’s Police Universities and People’s Institutes of Security. It can be taught as part of the curriculum and practiced without the appearance of religion, just like during the retreat in Wisconsin. Thay suggests that the head of the Department of Security International Cooperation may like to discuss with Dharma Teacher Cheri Maples in more detail about this proposal. It is possible that our Dharma teachers can also contribute to the teachings and practices at these training centers for policemen and other government officials. When we can benefit our country and its people, then even if we are accused of being communists, it is okay as long as the work helps people suffer less. If the policemen suffer, then the people will also suffer. When the police officers have internal suffering and they cannot resolve it, then their pain will be released onto their families and to the people. When police officers are corrupt and abuse their power, then not only is this a pity for the police officers and for the government, but also especially, a pity for the people. We should educate in such a way that the policies of the Departments can respond to the real needs of the people, then that education is truly beneficial.

My children, in history, every so often there is a great spiritual teacher who appears to purify and renew the Buddhist tradition. Those such as Nagarjuna, Deva, Asanga, Vasubhandu, Tran Na, Tzuantzan, the Sixth Patriarch Hui Neng, Linchi, Tri Gia, and Tang Hoi, were all revolutionaries who had the capacity to rejuvenate Buddhism, so that it can serve more effectively the new social situations. Great Teacher T’ai-hsu in the 30’s of the last century called for “Revolution in the teachings! Revolution in the precepts! Revolution in the properties!” Many people in the monastic circle in our country listened to this calling and worked hard to find ways to make Buddhism prosper. For Thay’s entire life, Thay has also tried to realize this calling. If there is no revolution of the teachings, it is difficult to apply the teachings into modern life. Therefore, from Engaged Buddhism we, in turn, have Applied Buddhism. If there is no revolution in the teachings, then the traditional precepts and mindful manners will not be able to confront the modern social crisis, the corruption and the social evils in our present society. That is why, now we have the revised Five Mindfulness Training, the revised Ten Novice Precepts, the Order of Interbeing, and the revised Pratimoksha. If there were no change in the teaching of handling property and possessions and we continue to be dependent on the offerings and donations of laypeople, then how can we have enough freedom to realize the revolution in the teachings and the precepts, and to contribute to work of purifying and building a society that is democratic and healthy. Without the revolution in the teachings, the precepts and in the monastic handling of property, then Buddhism will become decrepit, corrupted and lifeless and cannot continue to thrive or develop and will die out. A political organization is the same; if there is no revolutionary fire to nourish it, it will become decrepit and corrupted. It will go against its original aspirations, and the people who try to join the organization only do so because of benefits and not because of their ideals.

During the trip to Vietnam in 2007, Thay had a chance to personally visit and observe many temples in Hanoi. In the Buddha hall, in Patriarchs’ hall, on the front yard, wherever there were statues of the Buddha, the Boddhisattvas, Arhats, Patriarchs, Dharma Protectors, and Holy Mother displayed, money offerings were stuffed in the hands of these statues. Thay had the feeling that those Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Arhats, Patriarchs, etc. all became people who received bribes. They became the deities who only protected those who bribed them. This image shows us that the spirit world reflects our human world; reflecting the belief that those who do not accept corruption will not succeed and can not accomplish much. Thay questioned whether it is true that Bat Nha could not continue because Bat Nha did not accept this rule. Some people say that when the water is too pure, the fish can not live. Is this truth the case here? No, Thay does not want to believe in that truth. We have plenty of honorable people, true practitioners in our country who have not been bought out by fame or money. And you, Thay’s children, have been following their steps, even though around you, there are many monastics who have lost their beginner’s mind and who are looking only for material and emotional comforts to satisfy their life – a life deprived of meaningful ideals and a sense of brotherhood.

In the intellectual, humanitarian and political world, there are still people who have integrity and honesty; who would rather remain poor and than to loose their conscience. The father of our Elder Brother Phap Hoi was a very honest and upright cadre who was content with living modestly his entire life so as to nourish his integrity and virtue. Thanks to this, we now have Elder Brother Phap Hoi and so many others who, thanks to their faith in the traditional virtue of our country, are capable of maintaining integrity in their own life.

The Buddha-dharma seeds, the seeds of mindfulness practice that have been sowed in the last few years are beginning to sprout. Exposed to the practice, exposed to Sangha, the good seeds of deep aspiration and of happiness that have been in the hearts of these young people are beginning to grow fresh. The young monastics along with the young lay people have begun to see a beautiful spiritual path that can open up a new horizon of brotherhood and of a deep desire to service humanity. The ‘Cheri Maples’ of Vietnam are beginning to appear. There have some public security officers and young policemen who have come to practice with us and are beginning to transform. You have had some opportunity to befriend some of these officers. One police officer had confided his realization to us that when one’s mind is restless, one can not help bring peace to society, and with a distressed mind, one will only make the situation worse. That was the realization that Cheri Maples had also discovered. The heart-breaking case at Bat Nha is evidence of this disturbance in the hearts of the people. Because of fear, of resentment, of wrong perception, those responsible for security have caused such public disorder and have disgraced the image of our nation to the international community. One of those ‘Cheri Maples’ of Vietnam have expressed her intention to be ordained as a nun.

Only a few days ago, a young aspirant in Mountain Cloud Hamlet, named T.M.T wrote a letter that moved us and made us realize that the sacred fire of ideal and of brotherhood and sisterhood can be easily rekindled within young people’s souls. In her letter “Behind the Halo,” T.M.T. has shown her determination and willingness to release her constraints – the wealth, authority and influence – in order to ordain and live a simple and happy life with the deep aspiration of serving humanity and all of life. The whole family of T.M.T. was opposed to this and everybody considered her as being mad. What do you think of this, my children? If T.M.T was mad, then that madness is not different from the madness of Prince Siddhartha who renounced the throne to enter a monastic life. Who was Siddhartha? Siddhartha was a young man who had the determination to release everything and to search for a beautiful ideal. Siddhartha had the revolutionary fire in his heart, that provided him with enough energy to renounce his special privileges and comforts. Who is Siddhartha? Siddhartha is none other than T.M.T of today. We are the young people searching for this beautiful ideal. We are the continuation of Siddhartha. Siddhartha is there, present in our homeland so we can still have hope. Young people entering the monastic life have a very strong beginner’s mind, just like the young revolutionaries who also have a very strong beginner’s mind. We all have to maintain our beginner’s mind in order to succeed. With our beginner’s mind, we will not be weighed down by fame and wealth. Our beginner’s mind intact, we can still be free and liberated. The practice of the Buddha is to water the seeds of gratitude, of compassion, of wisdom and courage within us. The painful experience at Bat Nha has awakened the hearts of so many people inside and outside our homeland and has helped revive in them, the fire of ideal and the substance of courage. Poet Hoang Hung wrote in his article “Four Hundred Bat Nha Bells” that the petition letter he initiated calling for the protection of Bat Nha Sangha contained the signatures of well renowned people in the circle of Science, Literature and Art – people who “had never participated in any public expression against the government”. This means their seeds of compassion and courage were watered, so they did not hesitate to sign the petition letter. One of them confided, “In the past I was very afraid to get involve with such things, but this time if I did not raise my voice, it would be too cowardly and I would not be at ease with myself.” And of course after signing the letter, they were happy to know that they still had integrity in their hearts. The diligent practice of Thay’s Bat Nha children has watered the good seeds in people – Buddhist and non-Buddhist, inside the country and aboard, compatriots or foreigners. Those seeds are the seeds of faith, of love and of courage. The way of non-violence and of non-hatred of Thay’s children had evoked a trust towards a gentler humanism for the future, aroused a love in the people’s heart, and revived in everyone the virtue of non-fear that was already present it them. The Most Venerable monks have raised their voice. Buddhist novices have raised their voice. Students have raised their voice. Scholars and intellects have raised their voice. Small business people have raised their voice. Cadres and Party’s members have raised their voice. Friends from different religions have raised their voice. The world has raised their voice. Bat Nha, liked a fragrant lotus, has revived so much beautiful affection from the people. Our practice of “watering the good seeds” can bring about the harvest of love and happiness so quickly.

My beloved children, looking deeply, you will see that the people responsible for the disposal of the Bat Nha Sangha had acted contrary to what we practice. They only water the negative seeds. They threatened and lied in order to water the seed of fear in us. They said that Bat Nha Sangha is involved in politics. They said that the presence of Bat Nha Sangha is a threat to national security. They painted and foisted on the Bat Nha Sangha the word “reactionary.” A Major General from the Central Board of People’s Public Security Establishment was sent to confront the Bat Nha community as if you were a group of hostile reactionary. But on the contrary, you are but true practitioners that have no interest in politics and only want to practice in safety under the protection of the Buddhist Congregation and laws of the nation. They hired the poor and illiterate people, who were not Buddhist and knew nothing of Buddhist teachings, to do their work of attacking and expelling you out of the monastery. They lied to those people, saying that you were stealing the temple, you were the reactionary, you brought “snakes home to bite the chicken”, and you were a threat to national security. Essentially, they watered the seeds of misunderstanding, of suspicion and of hatred in the other compatriots. When these people lost their peace of mind, they were able to abuse, to destroy, to intrude on the monastery properties and to violate the human dignity of their own compatriots. How else can we have Buddhists who burn sutras, burn statues, throw excrements at the Venerables, tear at the monastics’ robes, drag monastics about like garbage bags and infringe on the monks’ private parts? Thay saw that their actions were very dangerous, and that those officials who hired such people, in the future, would become victims of those very same people.

Looking more carefully, we can see that not only the Bat Nha Sangha was a victim of a wrong policy, but local authorities and local people were also victims of this policy. Young public security officers and other administrative officials had received orders to eliminate Bat Nha and to do everything to accomplish this task, even though the task was contrary to the moral principles. People say, for the Party, for the regime, for the national security, even reluctantly we must carry out those tasks. We suppress ourselves to believe that we are doing it for the benefits of people and the nation. But from the depth of our consciousness we know those deeds are unrighteous, contrary to morality. Our conscience is disturbed. Members in our family look at us with doubt and resentment. Our compatriots look at us with scorn, contempt and disgrace. The suffering of a government official with a low wage is relatively small, compared to the gnawing conscience and the resentment from family members and compatriots; those are the real sufferings. Loss of peace and of self respect is a great suffering. That is an enormous loss. In a war, there are always great losses – the number of people killed, the number of people injured and missing. In the battles like the one at Bat Nha, although no one died but the damages were tremendous. The damages were to our human dignity, our conscience, our ideal, to the love of our homeland and to our country’s portrayal in the international stage. We not only did not improve our country but disgraced it instead, when we were forced to carry on those unjustly battles. In the end, all of us – young monastics, government officials and public security officers – are the victims.

A policy that benefits our country and its people is always based on the foundation of correct view, that in Buddhism we call “right view.” If our mind is covered by greed and desire, fear and doubt, then we cannot have right view, and our view is distorted and not true to reality. This view is called wrong view. To view Bat Nha as a menace to national security is a huge erroneous view. It is hard to understand how such an absurd event like that could have occurred? Because of that wrong view, there is wrong thinking, that by all means, Bat Nha must be eliminated. Wrong thinking leads to wrong speech and wrong actions. To say that the Bat Nha situation is an internal dispute, that the government and public security officers did not interfere with Bat Nha, that Bat Nha is involved with politics, and so on – all those statements are not right speech but wrong speech. Next, there is a sort of erroneous action called wrong action. The destruction, the expulsion, the arrests and the violations of human dignity – all these actions bring about suffering to the community that we vow to serve and suffering to our own self. The root of this suffering can all be traced back to wrong view. Because of that wrong view, we have wrong policies that are harmful to the nation and its people.

To resurrect faith and vitality in the Buddhist community, the genuine spiritual practitioners, especially those who no longer hold positions in the Buddhist organizations, have to find ways to come together. Because of fear and suspicion, people have deliberately controlled the Buddhist organization. And the method of control used so far is to infiltrate the organizations with their people so they can manipulate and control. Only a corrupted Buddhist dignitary could be manipulated. But if a dignitary is full of integrity, then they can not manipulate him. The infiltration into Buddhist organization with such corrupt people damages the organization. There were documents issued by the organization with a language that was not the true language of the Buddhist tradition. Everyone knows that those documents have been prepared in advance for the Buddhist dignitaries to sign. With such corruption, how can the Buddhist organization truly contribute as leader? If a religious organization was controlled to the point that it is paralyzed and does not dare to raise its voice to protect its children, then that organization no longer has enough trusted power, enough standing to lead.

So Thay thinks that the genuine senior practitioners should come together and raise their voice to lead the young generation of Buddhists and to transmit the necessary energy to the Buddhist organization so that this organization will have the opportunity to wake up and progress forward. This is also true for a revolutionary organization. The worthy senior revolutionaries must also come together and raise their voice. Raise their voice to lead the young generation, to arouse the trust in them and to help rekindle the sacred fire of the revolution that is dying in its own organization. To do whatever we can so that those joining the revolutionary organization have ideals, have enthusiasm of the youth, and have the capacity to let go of power and fame. Otherwise, the organization will only attract elements of opportunism who enter the organization with the only goal of seeking prestige and power. Such an organization is no longer a revolutionary organization, especially when its senior members, caught in positions and power, live an extravagant and luxurious life, possessing huge accounts of money hidden in foreign banks. Deprived of the revolutionary fire in their hearts, how can they call themselves comrades without feeling ashamed?

Because they wanted to disband Bat Nha, they fabricated stories stating that the monastics at Bat Nha are involved in politics, oppose the regime, oppose the congregation, and that Bat Nha must be dealt with as if it were a reactionary organization. “Pure water that one wants to stir into a paste” (A saying that means, the truth cannot be smeared into falsehood no matter how much one tries.) The letter of aspirant T.M.T has a sentence, “…to kill a dog, people must say it is a mad dog.” This is a law that has existed for thousands years and only idiots do not understand it. Why do you want to align with Bat Nha? That path leads to the door of death. If people want to destroy it, it will be destroyed; sooner or later, it is inevitable.

But certainly, Thay’s children have found that this Bat Nha case has become a special case. Because of your conduct, because of your pure drops of tears of non-violence and of non-hatred that everybody in the world has realized that it is not a mad dog or a crazy dog, and that maybe people would and could never kill this Bat Nha dog. Our neighbors, domestic and foreign, have seen that this is a smart dog and that we have to save its life because a smart dog can guard our doors and homes.

My dear children, please remember to breathe gently and deeply for Thay and walk mindfully and peacefully for Thay. And in whatever circumstance, we shall practice to treat each day wholeheartedly. We need to practice to live genuinely and to see things with the eyes of compassion. Today is the substance that builds tomorrow. Therefore, we have to live beautifully today. Thay has great trust and confidence in you. The healing energy of the Three Jewels are protecting all of us. You should diligently practice the gatha verse on “Taking Refuge in One’s Island.” Do not seek any other refuge besides the island within. These were the reminding words of the World Honored One.

Back in Plum Village, Thay will have the opportunity to continue to write you.

Your teacher,

Nhất Hạnh

Share Your Reflections