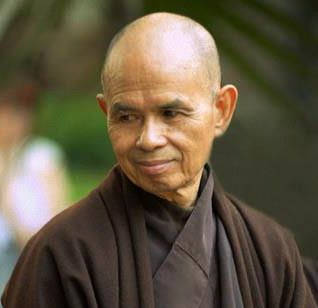

Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh’s compassionate response to the persecution of his students in Vietnam

“The koan “Bat Nha” is everyone’s koan; it is the koan of every individual and every community. The koan can be practiced by a Bat Nha monastic, by a monk or nun studying at a Buddhist Institute in Vietnam, a Venerable in the Buddhist Church of Vietnam, a police officer, a Catholic priest, a Protestant minister, a Politburo member, a member of the Central Committee, a newspaper or magazine editor, an intellectual, an artist, a businessman, a teacher, a journalist, an abbot or abbess, an international political leader or ambassador. Bat Nha is an opportunity, because Bat Nha can help you see clearly what you couldn’t – or didn’t want – to see before.”

Do not just look for what you want to see,

that would be futile.

Do not look for anything,

but allow the insight to have a chance to come by itself.

That insight will help liberate you – Nhat Hanh

Bat Nha is a monastery in the central highlands of Vietnam, it is a community of monks and nuns being persecuted by the Vietnamese government, and it is the great crisis of Vietnamese Buddhism at the dawn of the 21st Century.

A koan (known in Chinese as a gong an [公案], and in Vietnamese as a cong an [công án]) is a meditation device, a special kind of Zen riddle. Koans are solved not with the intellect but with the practice of mindfulness, concentration and insight. A koan can be contemplated and practiced individually or collectively, but so long as it remains unsolved, a koan is unsettling. It is like an arrow piercing our body which we cannot take out; so long as it is lodged there we can neither be happy nor at peace. Yet the koan’s arrow has not really come from outside, nor is it a misfortune. A koan is an opportunity to look deeply and transcend our worries and confusion. A koan forces us to address the great questions of life, questions about our future, about the future of our country and about our own true happiness.

Some of the best known Zen koans include “The cypress in the courtyard”, “If everything returns to the one, where does the one return to?”, “Does a dog have Buddha nature?”, and “Who is invoking the Buddha’s name?” Vietnam’s great leaders and statesmen have long practiced the art of contemplating koans, and contributed many famous ones of their own1. Zen Master Tue Trung, whose brother General Tran Hung Dao repelled Genghis Khan’s invasion, offered the powerful koan “All phenomena are impermanent. Everything that is born must finally die. What is born, and what dies?”

A koan cannot be solved by intellectual arguments, logic or reason, nor by debates such as whether there is only mind or matter. A koan can only be solved through the power of right mindfulness and right concentration. Once we have penetrated a koan, we feel a sense of relief, and have no more fears or questioning. We see our path and realize great peace.

“Does a dog have Buddha nature?” If you think that it’s the dog’s problem whether or not he has Buddha nature, or if you think that it’s merely a philosophical conundrum, then it’s not a koan. “Where does the one return to?” If you think this is a question about the movement of an external objective reality, then that is not a koan either. If you think Bat Nha is only a problem for 400 monks and nuns in Vietnam, a problem that simply needs a ‘reasonable and appropriate’ solution, then that too is not a koan. Bat Nha truly becomes a koan only when you understand it as your own problem, one that deeply concerns your own happiness, your own suffering, your own future and the future of your country and your people. If you cannot solve the koan, if you cannot sleep, eat or work at peace, then Bat Nha has become your koan.

‘Mindfulness’ means to recollect something, to hold it in our heart day and night. The koan must remain in our consciousness every second, every minute of the day, never leaving us even for a moment. Mindfulness must be continuous and uninterrupted; and continuous mindfulness brings concentration. While eating, getting dressed, urinating and defecating, the practitioner needs to bring the koan to mind and look deeply into it.The koan is always at the forefront of your mind. Who is the Buddha whose name we should invoke? Who is doing the invoking? Who am I? You must find out. So long as you haven’t found out you haven’t made the breakthrough, you are not yet fully awake, you have not understood.

I AM A MONASTIC FROM THE BAT NHA COMMUNITY. Bat Nha is my koan and I have the opportunity to look deeply into it in every moment of my daily life. Every day I contemplate the koan of Bat Nha – I sit with it in meditation, I walk with it in mindfulness, I am with it when I cook, when I wash my clothes, peel vegetables or sweep the floor; in every moment Bat Nha is my koan. I must produce mindfulness and concentration, because for me it is a matter of life and death, of my ideals and my future.

We know we’ve been successful in our practice, because despite all the oppression and harassment, many of us in our community can still laugh and be fresh as flowers. We are still able to generate peace and love, and not be dragged down by worries, fears or hatred. Yet there are those of us who are still suffering, weighed down by the trauma of the days when Bat Nha and Phuoc Hue Temple were attacked. One of the nuns offered an insight poem to our teacher. She wrote, “The Bat Nha of yesterday has become rain, falling to the earth, sprouting the seed of awakening.” This nun is barely 18 years old, not even two years ordained, but she has successfully penetrated the koan of Bat Nha.

All we want is to practice – why can’t we? The senior monks of Vietnam want to protect and sponsor us – so why does the government stop them? We don’t know anything about politics, it doesn’t interest us at all – so why do they keep accusing us of meddling in politics and saying Bat Nha is a threat to national security? Why was dispersing Bat Nha so important that they had to resort to using hired mobs, slander, deceit, beatings and threats? The attackers were the age of our fathers and uncles; how could they have done that to us? If the government forbids us from living together and forces us, down to the last person, to scatter in all directions, how will our community ever be reunited? Why is it that in other countries people can practice this tradition freely, and we can’t?” These questions come up relentlessly and will not go away. They yearn to be answered.

During the time of sitting meditation, walking meditation, or listening to a Dharma talk; while cooking, gardening, or doing other work in mindfulness, we generate the energy of mindfulness and concentration. This energy is like fire that burns away all the haunting thoughts and questions.

The Bat Nha of yesterday was happiness. We could be true to ourselves and live the way we wanted to live. For the first time in our lives we were in an environment where we could speak openly and share our deepest thoughts and feelings with our brothers and sisters – without suspicion, without fear of betrayal. We had the opportunity as young people to serve the world, in the spirit of true brotherhood and sisterhood. This was the greatest happiness. Then Bat Nha became a nightmare, but no-one will ever take from us the inner freedom we discovered there. I have found my path. Whether or not Bat Nha exists, I am no longer afraid. I can see that Bat Nha has become rain, helping the indestructible diamond seed of awakening to sprout within us. Even though we were forced from Phuoc Hue, and Bat Nha is no more, the seeds of awakening that have been planted in our hearts can never be taken away. Thay has taught each one of his students to become a Bat Nha, a Phuong Boi2. We are Thay’s continuation and we know that we will make many more Bat Nha’s and Phuong Boi’s in the future.

We already have the seed and we already have our path, so we are no longer afraid for the future – our own, or that of our country. Tomorrow we will have the chance to help those who persecute us today. They may not see that now, but later they will understand. We know that many of those who attacked us and made us suffer have already begun to see the truth. Prejudices and wrong perceptions like those that built the Berlin Wall eventually collapse and disintegrate. There is no need to worry or despair. We can laugh as brightly as the morning sun.

I AM A CHIEF OF POLICE IN VIETNAM. At first, I believed that the order from my superiors to wipe out Bat Nha must have been justified, that it must have been in the interests of national security. I trusted my superiors. However, as I carried out the order, I saw things that broke my heart. Bat Nha has become a koan for my life. I can’t eat, I can’t sleep. I toss and turn throughout the night. I ask myself, What have these people done, that I should treat them as reactionaries and threats to public safety? They seem so peaceful – but I have no peace at all. If I don’t have peace in my heart, how can I keep the peace in my society?

The young monks and nuns have not broken any laws. In fact we were the ones who collaborated with those who seized their property. We forced them to leave the place they helped to build, where they had been living peacefully for years. We tried everything to force them out, yet they held their ground. They seemed to have so much love for each other – there seemed to be something that bound them together. They lived with such integrity. Even though they were young, none of them was pulled into smoking, drug abuse or empty sex. They lived simply, ate vegan food, sat in meditation, listened to sutras, shared with each other and did no harm to anyone. How can we say they are dangerous? They have never said or done anything against the government. We cannot truthfully say they are reactionaries or involved in politics. And yet we have accused them of that and driven them out by every possible means: we threatened them, we cut off their electricity and water, we went every night for many months to harass them, demanding to see their identification papers, over and over again; we did everything we could to break their spirit. But they never said a reproachful word, they offered us tea, they sang for us and they asked to take souvenir photos with us.

In the end we hired mobs to destroy their community, to assault them and expel them. We had to be there wearing plainclothes to identify and single out the leaders so the thugs could neutralize and abduct them. Not once did they fight back. Their only weapons were chanting the Buddha’s name, sitting in meditation, and locking arms to stop us from separating them as we forced them into the waiting cars. Central government even sent a Major General to coordinate the attack. Why did we need to mobilize such a massive force, from the central to the local government, to break up a group of young people with empty hands and innocent hearts?

And why did it take us more than a year to kick them out? What was there in the temple that made them so determined to stay? Every day they had just two vegan meals, three sessions of sitting meditation, one lecture and one session of walking meditation. Why were there so many of them, so young and yet living so harmoniously with each other? Some of them had university diplomas, some were sons and daughters of high-ranking officials, some had had careers and high-paying jobs; but they left it all behind for a humble life. What was so good there that it attracted so many young people? How can we just say that they were tricked by the honeyed words of a person living in the West into opposing the government?

My orders came from above and I had to obey; but I feel deeply ashamed. At first I thought they were just temporary measures, for the greater good of the country, for the sake of preserving national unity. Now I know that the whole operation was deceitful, cruel and offensive to human conscience. I am forced to keep these thoughts to myself. I don’t dare to share them with the officers in my unit, let alone my superiors. I can’t go forward and I can’t go back; I am a cog in a machine and I can’t get out. What must I do to be true to myself?

I AM A MEMBER OF THE BUDDHIST CHURCH OF VIETNAM. Bat Nha haunts me night and day. I know those young monastics are practicing the true Dharma. Everyone who has come into contact with them confirms this. So why are we powerless to protect them? Why do we have to live and behave like government employees? When will I realize my dream of practicing religion without political interference? During the periods of foreign colonization, or the Diem and Thieu regimes, Buddhists faced hardships; but monastics were never as tightly controlled as they are now. What the officials want today is a Buddhism based on blind faith and rituals, not a Buddhism that offers true spiritual guidance and has the capacity to promote an ethical way of living. They are afraid of a Buddhism that offers powerful spiritual leadership, and only accept religious organizations that can be controlled and manipulated. But when the Buddha was alive, he refused to submit to domination, even that of King Ajatasattu. During the French colonization and the Diem, Ky and Thieu regimes, our ancestors fought for liberty. Why are we not continuing that work? Why have we allowed ourselves to become the instruments of a policy that is trampling our ideal of service, our noble aspiration of awakening?

At first, I thought that if I went along with the government, I would at least have a chance to do some of the ‘Buddha’s work,’ whereas if I opposed the government totally then I wouldn’t be able to do anything. And so I had to silently suffer the criticism and scorn of my colleagues for being in the system. After a while, however, I saw that it was thanks to the ability and courage of those outside the Buddhist Church to voice their protests that I was permitted to do Buddhist work, albeit in a limited way. When the history of Vietnamese Buddhism is written, how will I answer for this? My aim was to revive Buddhism in order to serve the people and the nation, not to become part of a system that exists to monitor and control Buddhists.

That venerable, who was pressured into withdrawing his sponsorship for the monks and nuns to stay and practice at his temple: he did not have the strength to resist. He was compelled to betray his teacher and his friends and break the deep vow he made just a few years ago. It is a tragedy for him. But who is that monk? Is he someone else, or is he none other than myself? He is in me. I am also being pressured, and don’t dare to do or say what I really believe in order to protect my spiritual children and young brothers and sisters. Isn’t it my deepest desire to ‘Guide the future generations, and repay my debt of gratitude to the Buddha?’ If so, then how can I justify the fact that I stood by helplessly and watched as the young monks and nuns, my spiritual descendents, were oppressed, humiliated and trampled upon? How can I dare to look my spiritual children, my continuation, in the eyes? What is my true face? Who am I?

We are brothers and sisters, children of the Buddha. Is it because our practice of brotherhood is not solid enough that they have been able to divide us, that we have fallen into blaming and hating each other? According to the Buddha’s teaching of non-dualism, whether we follow the Unified Buddhist Church or the Buddhist Church of Vietnam, we are still brothers and sisters in the same family. We can do what we have to do without fighting or opposing each other, without having to consider each other as enemies. Has this enmity arisen because our practice is still weak? Has this happened because our spiritual power is not great enough? But surely we have learned a lesson: if we can accept each other and reconcile with one another, we can still resurrect our brotherhood and sisterhood, inspire the confidence of our fellow citizens and be role models for everyone. Even though we’ve left it until it’s too late, the situation can still be saved. Just one moment of awakening is enough to change the situation.

It seems the monks and nuns of Bat Nha have learned this lesson. Even when they were attacked and expelled they never showed any resentment toward the venerable abbot who had taken them in during these years. They knew that he was under intense pressure to force them out and that eventually he crumbled. If we in the Buddhist Church have been cornered into betraying our own brothers and sisters it is because our spiritual integrity is not yet strong enough. How can we be wholehearted and determined enough in our daily practice to attain the spiritual strength we need? Only when we understand can we love. When we love each other we cannot see each other as enemies. As long as we see each other as enemies, we will fall prey to schemes of division and separation.

Bat Nha isn’t just an issue for the Central Buddhist Church of Vietnam to resolve. Bat Nha is a koan, the challenge of our lives. How can we solve it in such a way that we are not ashamed before our ancestors? Why can’t I share my thoughts and feelings with my friends in the Central Buddhist Church of Vietnam? Why aren’t we allowed to harmonize our views? Why do we have to hide our thoughts and feelings?

Vietnamese Buddhists have respected and followed the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha for the last two thousand years. But now groups of people were hired who wore shoes into the Buddha Hall, who put up offensive banners on the altar, who yelled and cursed and threw human excrement at venerable monks, who destroyed sacred objects, and who violently attacked, beat and expelled monks and nuns from their temple. It was government officers who hired them and said they were Buddhists. This is an ugly stain on the history of Buddhism in Vietnam. It disgusts us and sickens us, yet why don’t we dare to speak out? Can the Buddhist Church of Vietnam, whose members were slandered, falsely accused and framed by the government, shake off this insult and prove the innocence of Vietnamese Buddhists?

I AM A HIGH RANKING MEMBER OF THE COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT OF VIETNAM. Bat Nha is an opportunity for me to look deeply at the truth and find peace in my own heart and mind. If I don’t have peace, how can I have happiness? But how can I have peace, when I don’t really believe in the path I walk on, and especially when I don’t have faith or trust in those I call my comrades? We may be bedfellows, but are we dreaming different dreams? Why can’t I share my real thoughts and feelings with those I call my comrades? Am I afraid of being denounced? Of losing my position? Why do we all have to say exactly the same things when none of us believe it? Isn’t this a case of The Emperor’s New Clothes, where all the members of the Emperor’s court swear the Emperor is wearing a beautiful robe, when in fact he is completely naked?

My greatest dream is for my own happiness to be in harmony with my country’s. Just as trees have their roots and water has its source, our homeland has its heritage of spiritual insight. The Ly dynasty was the most peaceful and compassionate dynasty in our country’s history. Under the Tran dynasty, the People’s unity was strong enough to enable them to push back the attacks from the North. This unity was possible thanks to Buddhism’s contribution as an inclusive and accepting spiritual path, that could co-exist with other spiritual and ethical traditions, such as Taoism and Confucianism, and so build a country that never needed to expel or eliminate anyone.

I’ve had the opportunity to study. I know Buddhism is not a theistic religion but is solidly humanist. Buddhism is open-minded and undogmatic; it has the spirit of rational enquiry. In the new century, Buddhism can go hand in hand with science. ‘Science’ here means the spirit of scientific inquiry, the willingness to let go of old views in order to embrace new ones that are closer to reality. Modern science has gone far beyond traditional science, especially in the area of quantum physics. Is what I took for science in the past still science today? Mind and matter are just two manifestations of one reality. They contain one another and depend on one another to manifest. Modern science is putting all its energy into overcoming dualistic ways of thinking – about mind and matter, inside and outside, subject and object, space and time, mass and speed, and so on. If I am still caught in my anger, anxiety, craving and discrimination, then my mind cannot be collected and concentrated enough to see the truth. No matter how sophisticated the instruments are that I use, behind all that technology there is still the mind that observes.

In my heart I know that the people supported the revolution so strongly because they loved their country, not an ideology. If the people’s support had been based only on an ideology, and not on their deep love for the country, then we would surely have failed. I know that in the 1940s some of us, out of zealous and fanatical devotion to an ideology, crushed and assassinated revolutionaries fighting alongside us against foreign aggressors. To this day, the wounds of that time have not been healed.

As for class struggle, I should ask myself: Which class is holding power now? The proletariat or the capitalists? Is there such a thing as ‘The People’s Capitalism’, or is that just a convenient fiction?

If we want to be successful, the Party’s policy must reflect the People’s deep wishes (Y Dang, Long Dan). The People’s deep wish is for monks and nuns to have the freedom to practice and help the world according to their ideal, in line with the laws of the land. The People’s deep wish is for every citizen to be able to speak his or her mind without fear of denunciation or arrest. The People’s deep wish is to separate religion from political affairs, and take the politics out of religion. If the deep wishes of the People are satisfied, then there will naturally be unity, and the Party will be supported. If the Party were in harmony with the hearts of the People, the Party would no longer need to appeal for unity or support. Such is the wish of the People. What is the policy of the party?

I know that during the Tran and Ly dynasties, Buddhism’s spirit of inclusiveness united the whole nation. Thanks to that spirit, everyone who loved their country had an opportunity to contribute to the work of building and protecting the nation, and no-one was excluded. This spirit of inclusiveness in Buddhism is called ‘equanimity’, and is one of the four Buddhist virtues, alongside loving kindness, compassion and joy. Inclusiveness is a precious spiritual heritage, a cultural treasure. I know that during the Ly and Tran dynasties, kings and politicians practiced Buddhism just as the people did. By keeping the Buddhist precepts, following a vegetarian diet and doing good works, they were able to earn their people’s trust and confidence.

How can we eradicate the hideous social evils of drug abuse, prostitution, gambling, violence, corruption and abuse of power, when the officials responsible for abolishing them are themselves caught up in those very evils? How can the government’s policy of ‘cultural districts’ and ‘cultural villages’ ever be successful if it is based merely on perfunctory inspections and punishment? Who is the one that needs to be inspected and who is the one that needs to be punished?

I know that any family that practices and keeps the mindfulness trainings enjoys peace, joy and happiness. For the last two thousand years, Buddhism has been teaching people how to live ethical lives, be vegetarian and keep the trainings. Following a vegetarian diet is a sign of mastery over the craving mind, of not giving in to desires. When Buddhists observe a vegetarian diet, keep the trainings and do good deeds, they do so voluntarily and not by force or fear of punishment. At this very time, the young monks and nuns of Bat Nha are going in this direction, reinvigorating this ethical way of living. They have the potential to succeed. So why do we want to repress them and wipe them out? Are we afraid that if they have mass support, it will be at our expense? Why can’t I open my heart to practice like them, to be one with them and benefit from their support? Why can’t we do as the kings of the Tran and Ly dynasties did? Just because we are Marxists, does that mean we don’t have the right to take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, to be vegetarian and practice the mindfulness trainings?

I know that in the party and in the government, many people now claim to be open-minded towards religion and spirituality. In fact, all the top officials believe in things like feng shui, destiny, psychic powers and even the idea of extending one person’s lifespan by transferring life-years from someone else. They have gone from one extreme to another. And yet they outwardly claim not to be superstitious.

The Ly and Tran kings truly believed in a path of virtue and spirituality. Many of them lived exemplary ethical lives, and the people had confidence in them and were inspired to do the same. One king knew how to practice the mindfulness trainings, followed a vegetarian diet, sent blankets to prisons, and went out into towns and villages to meet the people and see the truth of how they lived and what they suffered. A king who knows how to do sitting meditation, look deeply into koans, practice beginning anew six times daily, write commentaries on sutras, take refuge in the wise counsel of a Zen master whom he respects as the national teacher, and yield the throne to his son in order to become a simple monk on Yen Tu mountain – such a king can be a great example of morality for the whole nation.

Nowadays we’re always urging government officials and one another to “study and follow the virtuous example of Ho Chi Minh”. But who is the one that is living a good example for their comrades? Mahayana Buddhism teaches that “You have to be that person. You have to be the role model. You have to live that way yourself. Only then will you give others the inspiration to do the same.” I have to be that person. I know that corruption and abuse of power have become a national catastrophe. We have been lamenting it for so many years already, and yet the situation just gets worse with every passing day. Why? Is it because I’m only able to proudly boast of my ancestors’ glorious past, and am not in fact able to do as they did? And today, when there are young people actually doing it, why do we block and suppress them?

The Bat Nha situation may have started with a travel agency owned by a high police officer. Soon it involved hotels, then visas, and eventually the abuse of power and the exercise of revenge. Now it has become a policy the whole country has to follow. Maybe I have not taken the time to examine this. I just go along with the false reports and casually allow the people I am supervising to use lies, deception and oppression against these gentle people who never have caused any disturbance to society. In the end I am put in a position where I become the enemy of the very things I once cherished. Are my true enemies really outside of me? My enemies are within. Do I have enough courage and intelligence to face my own weaknesses? That is the fundamental question.

The Plum Village practices offer a rare opportunity to modernize Buddhism in Vietnam; the last four years have proved their effectiveness. Why are we allowing ourselves to be pressured by our powerful neighbor into persecuting and destroying such a precious living treasure? What will we get that is so precious, in return for destroying this treasure we already have?

The best way to celebrate the thousand-year anniversary of Hanoi is to strive to practice, to live like our great ancestors Ly Cong Uan, Tran Thai Tong, Tran Thanh Tong, Truc Lam Dai Si, and Master Tue Trung. They were politicians, but at the same time lived a true spiritual life that they believed in. What have I to be proud of, other than the legends of my ancestors? I have lost my revolutionary ideal. I have snuffed out the sacred flame of my aspiration. My comrades are no longer truly my comrades because their own sacred flame of revolutionary idealism has gone out. They are only in the Party for self-interest, fame and status. The Plum Village tradition is part of my country’s cultural heritage and is contributing to a global cultural ethic – not just in theory but, most importantly, in practice. So many people all around the world have heard about this tradition and are benefiting from these teachings. I should be proud of this, so why did I allow the tradition to be attacked and wiped out in the very land where it was born? These are the questions that, if allowed to penetrate and act upon the depths of my consciousness, can awaken the wisdom within. This will give me the insight I need to see the path and way out I have been longing for.

I AM A HEAD OF STATE OR FOREIGN MINISTER. My country is or is not a member of the Security Council or the UN Commission on Human Rights. I know that events like Bat Nha, Tam Toa, Tiananmen Square and the annexation of Tibet are serious violations of Human Rights. But because of national interest, because our country wants to continue to do business with them, because we want to sell arms, airplanes, fast trains, nuclear power plants and other technologies, because we want a market for our products, I cannot express myself frankly and make real decisions that can create pressure on that country so they stop violating human rights.

I feel ashamed. My conscience is not at peace but because I want my party and my government to succeed, I tell myself that these violations are not serious enough for my country to take a stance. It seems that I too am caught in a system, a kind of machinery, and I cannot really be myself. I’m not able to give voice to my real feelings or to speak out about the situation. What do I have to do to get the peace that I so badly need? Bat Nha is of course a situation in Vietnam, but it has also become a koan for a high-ranking political leader like me. What path can I take in order to really be myself?

The koan “Bat Nha” is everyone’s koan; it is the koan of every individual and every community. The koan can be practiced by a Bat Nha monastic, by a monk or nun studying at a Buddhist Institute in Vietnam, a Venerable in the Buddhist Church of Vietnam, a police officer, a Head of Department, a Catholic priest, a Protestant minister, a Politburo member, a Chairman of a city’s People’s Committee, a Provincial Party Secretary, a member of the Central Committee, a newspaper or magazine editor, an intellectual, an artist, a businessman, a teacher, a journalist, an abbot or abbess, an international political leader or ambassador. Bat Nha is an opportunity, because Bat Nha can help you see clearly what you couldn’t – or didn’t want – to see before.

In the Zen tradition, there are retreats of seven, twenty-one and forty-nine days. During these retreats, the practitioner invests their whole heart and mind into the koan. Every moment of their daily life is also a moment of looking deeply: when sitting, walking, breathing, eating, brushing their teeth or washing their clothes. At every moment the mind is concentrated on the koan. The most popular retreat is the seven-day retreat. Every day the practitioner gets the chance to interact with the Zen master in the direct guidance session. The Zen master offers guidance to help the practitioner direct their concentration in the correct way, opening up their mind and helping them to see, showing them the situation so the truth can reveal itself clearly.

In the direct guidance sessions the truth is not transmitted from master to practitioner. Practitioners must realize the truth for themselves. The Zen master may give about ten minutes of guidance, to open your mind and point things out, and then everyone returns to their own sitting place to continue to look deeply. Sometimes there are hundreds of practitioners, all sitting together in the meditation hall, facing the wall. After a period of sitting meditation, there is a period of walking meditation. Practitioners walk slowly, each and every step bringing them back to the koan. At meal times, practitioners may eat at their meditation cushion. While eating they contemplate the koan. Urinating and defecating are also opportunities to look deeply. Noble silence is essential for meditative enquiry, and that is why outside the meditation hall there is always a sign that reads ‘Noble Silence.’

In the past, King Tran Thai Tong became enlightened by investigating the two koans ‘Four mountains’ and ‘A true person has no position’. Zen master Lieu Quan became enlightened thanks to his practice of the koan ‘The all proceeds to the one; where does the one go?’. He presented his insight at Tu Dam Temple in the city of Hue.

If you want to be successful in your practice of koans, you must be able to let go of all intellectual knowledge, all notions and all points of view you currently hold. If you are caught in a personal opinion, standpoint, or ideology, you do not have enough freedom to allow the koan’s insight to break forth into your consciousness. You have to release everything you have encountered before, everything you have previously taken to be the truth. As long as you believe you already hold the truth in your hand, the door to your mind is closed. Even if the truth comes knocking, you will not be able to receive it. Present knowledge is an obstacle. Buddhism demands freedom. Freedom of thought is the basic condition for progress. It is the true spirit of science. It is precisely in that space of freedom that the flower of wisdom can bloom.

In the Zen tradition, community is a very positive element. When hundreds of practitioners silently look deeply together, the collective energy of mindfulness and concentration is very powerful. This collective energy nourishes your concentration in every minute and every second, giving you the opportunity to have a breakthrough in your practice of the koan. This kind of environment is very different from that of a conference, discussion or meeting. The firm discipline of your meditation practice, the favorable environment for concentration, as well as the guidance of the Zen master and silent support of fellow practitioners, all provide you with many opportunities to succeed.

The suggestions given above can be seen as direct guidance to help you in your practice of looking deeply. You have to see these words as an instrument, not as the truth. They are the raft that can bring you to the other shore; they are not the shore itself. Once you reach the other shore, you have to abandon the raft. If you are successful in looking deeply, you will have freedom, you will be able to see your path. Then you can just burn these words, or throw them away.

I wish you all success in the work of looking deeply into the Bat Nha koan,

Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh

Sitting Still Hut, Upper Hamlet

Plum Village, France

19 January 2010

1. Long ago, Vietnam’s King Tran Thai Tong practiced Zen. He meditated on koans and contributed forty new koans, as well as various invocations, recitations and short verses, for friends to practice with him at the palace’s True Teachings Temple. These koans have been recorded in his book, Instructions on Emptiness. Master Tue Trung, a lay man, composed thirteen of his own koans, which are recorded in the Record of Zen Master Tue Trung. The Blue Cliff Record, edited by Zen master Yuan Wu in the twelfth century, has over 100 koans complete with teachings, commentaries and guidelines. This classic has been used by Zen practitioners for centuries.↩

2. Thich Nhat Hanh’s first monastery, Fragrant Palm Leaves, founded in the 1960’s near where Bat Nha was later built.↩

Share Your Reflections