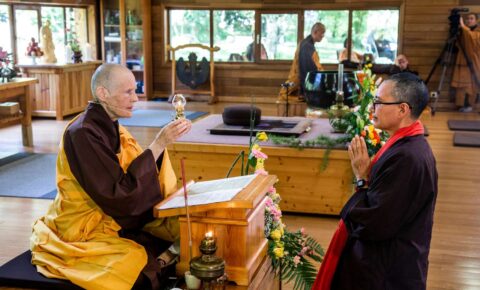

Sister Bội Nghiêm interviews US Dharma Teachers Valerie Brown and Juliet Hwang to share their experience-based insights on the necessity of BIPOC spaces and groups in cultivating a key sense of safety for practitioners of Color and in preparing the ground for individual and collective transformation and healing.

Sister Boi Nghiem: What were your early experiences as BIPOC participants in Plum Village retreats?

Valerie: My journey with Plum Village began in 1994 when I attended a public talk by Thich Nhat Hanh at the Riverside Church in Manhattan. I don’t remember much of what Thay said that day, but I vividly recall how I felt. At the time, I thought, “This isn’t for me.” The teachings – about cultivating peace and compassion within oneself and sharing that with others – felt far removed from my lived reality. My life was centered on survival. I was raised by my mother who was a single parent working two jobs and supporting four children. I grew up in New York City with poverty, violence, and childhood trauma.

When I arrived at the talk that day, I was navigating my career as a lawyer-lobbyist and was very much caught in fear, aggression, and confrontation, which was the legacy of my childhood. My focus was on making money and becoming “somebody.” Looking back, I am not proud of that. I was doing the best I could at the time. Though I walked out of the talk that day very skeptical, I knew deep inside that Thay’s words were true and revealed a path for me. Taking that path would mean change for me – lots of change – and I decided to begin, slowly.

In the early 2000s, I started attending Plum Village retreats. Gradually, and with the support of the sangha, I started to feel differently: less anger and hostility, less aggression. Yet, those early experiences were far from easy. I was unlearning so much, and I was learning to really stop and look deeply at my life. At the time, the retreats were almost entirely white. I was often one of the only BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) participants. I felt like an anomaly. People would ask me questions like, “What are you doing here?” or “Why do you stay?” Some of these questions were rooted in genuine curiosity, but they only amplified my sense of isolation as a Black woman in a predominantly white space. Many BIPOC participants who attended retreats shared similar experiences of feeling judged or unsafe. Many didn’t return.

Despite the challenges, I stayed. The practice benefited me profoundly. I had to unlearn harmful patterns and beliefs, and I am deeply grateful for the sangha and the community that supported my transformation. Early on, I found connection with others like Sister Jewel and lay Dharma teacher Larry Ward, but the experience was still isolating. Looking back, I see that the environment – while rooted in love, compassion, and service – wasn’t fully equipped to address the unique needs of BIPOC practitioners. We bring with us our inherited social conditioning and the habit energies of our experiences, as well as societal legacy burdens of prejudice, discrimination, and more. When these realities go unacknowledged, they can create barriers, even in a space as loving as a Plum Village retreat.

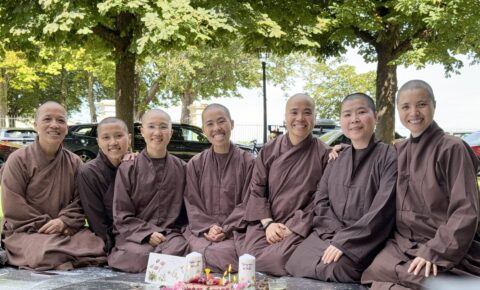

Today, the story is different. There has been a collective effort to increase diversity and create spaces where BIPOC practitioners feel welcomed and supported. Groups like the ARISE Sangha and initiatives for BIPOC Dharma Sharing have flourished. Non-BIPOC practitioners have also engaged in deeper self-reflection, especially after events like the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Yet, there’s still much work to do. Representation in teaching roles and among attendees remains unbalanced, both at Plum Village and in Buddhist centers across North America. Addressing these disparities is vital for the sangha’s growth and health.

Juliet: My first experience at a BIPOC retreat was in 2004 at Deer Park Monastery. It was the first BIPOC retreat led by Thay and the monastic community, and it remains one of the most profound experiences of my life. I was a pediatric resident, feeling burnt out by a harmful healthcare system. Thay laid out the groundwork for us to recognize, embrace, and transform suffering. He showed us how to heal. He also showed me how I can help others heal by offering my deep presence. The retreat was alive with energy – filled with laughter, joy, and love, alongside deep acknowledgment of suffering and pain. What made the retreat transformative was the sense of safety that permeated the space. For the first time, I felt safe enough to fully be myself and embrace the depth of my suffering.

Reflecting on it now, I see that this sense of safety came from the collective energy of the sangha. It allowed us to be vulnerable, to share openly, and to heal together. I didn’t have to explain myself or justify my experiences. I was seen, heard, and held in a way I had never experienced before. That safety gave me the courage to begin my journey of transformation. I’ve also witnessed the harm caused by the absence of such spaces in the past. Many BIPOC individuals who attended retreats before the creation of dedicated BIPOC spaces didn’t feel welcome or supported. They often left carrying feelings of hurt and exclusion. This painful reality continues to motivate me to create inclusive spaces where BIPOC practitioners can thrive. Over the years, I’ve seen tremendous growth in these efforts. Spaces like the Lotus in a Sea of Fire sangha for BIPOC OI aspirants now provide the support and nourishment needed for BIPOC practitioners to heal and grow. These spaces are essential for cultivating the collective transformation and liberation that Thay envisioned for our sangha.

Sister Boi Nghiem: Why is safety such a recurring theme in BIPOC retreats, and how does it contribute to transformation?

Valerie: From my perspective, as someone studying trauma and mental health, safety isn’t just a concept – it’s a biological imperative, fundamental to the human experience. Without it, our nervous systems stay in a state of hypervigilance, impacting our ability to experience joy, trust, and peace. For many BIPOC individuals, systemic oppression and intergenerational trauma have conditioned our bodies to be on high alert. (BIPOC too have inherited intergenerational strength, resilience, and joy.) Research shows that perceived discrimination and unsafe environments elevate stress hormone cortisol levels and contribute to allostatic load – that is, physiological dysregulation due to the cumulative burden of chronic stress – leading to long-term health challenges. Safety allows the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for fear responses, to reset. This resetting creates the conditions for deeper engagement with the practice and for true healing to occur.

BIPOC retreats prioritize creating environments where participants feel safe – physically, emotionally, and spiritually. When participants come to a BIPOC retreat and feel genuinely safe, their bodies begin to relax, their minds open, and their hearts can touch the teachings in a profound way.

Juliet: Safety isn’t just the absence of harm – it’s the presence of love, care, and understanding. It isn’t only about the physical space – it’s about the environment, the community, and the collective energy. It’s about being surrounded by people who look like you, who share similar experiences, and who extend a hand in friendship. BIPOC retreats provide a space where we can experience co-regulation of our nervous system by being in safe connection with other BIPOC individuals; they create environments where people feel held and supported. They allow people to embrace their full humanity, to connect with the teachings in a way that feels authentic and embodied, creating the foundation where the nervous system can relax and deep healing can occur. These moments of transformation are deeply connected to the unique conditions that BIPOC retreats create. This is why safety is a recurring theme – because without it, transformation cannot happen.

One story that stands out for me is of a woman who shared how she had always felt unsafe walking into predominantly white meditation spaces, which is a common sentiment among many BIPOC. At a BIPOC retreat, she said she finally felt a sense of belonging. That sense of safety allowed her to engage more deeply with the practice and experience a transformation that had eluded her in other settings. These stories are a testament to the power of a beloved community and the importance of creating spaces where BIPOC individuals can feel seen, heard, and held. Without these conditions, the true potential of the practice remains out of reach for many.

Read the article in full in the Plum Village Newsletter.

Resources

- ARISE Sangha

- Regulating the Nervous System – Juliet Hwang

Share Your Reflections