By: Ray Hemachandra

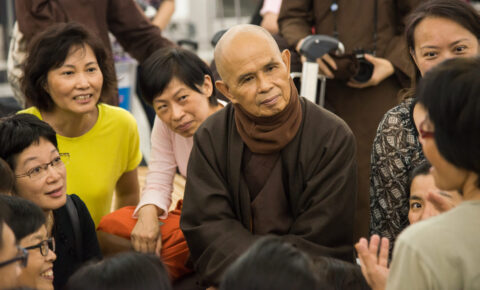

In September I drove to Magnolia Grove Monastery in Batesville, Mississippi, to spend a day at a retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh and Zen Buddhist monks and nuns both from this monastery and mindfulness meditation practice center and from Plum Village in France.

In many ways this felt long in coming. Years earlier — maybe ten or so years ago, when I still lived in Bellingham, Washington — I had been offered the chance to interview Thây (pronounced “tie,” translates as teacher, and the name by which Nhat Hanh is mostly called, respectfully and fondly). I was editor in chief of a trade magazine, New Age Retailer, and did many such interviews back then, in Seattle or Vancouver or at trade shows in Denver or Orlando. Or, not infrequently, over the phone, but this was one interview I felt compelled to do in person: Thây’s teaching had so impacted my life. The publication didn’t pay for travel for an interview, though — the cost of the travel alone far exceeded what we were able to pay for articles back then — and I wasn’t, well, mindful enough at the time just to pay for the trip myself. So I missed the chance.

In 2009, having moved a few years before to Asheville, North Carolina, from Bellingham, I learned Thây was doing another U.S. tour, with retreats at the several monasteries he established in the United States. During this time I was writing several freelance pieces a year for a consumer magazine sold primarily in what were the three major domestic bookselling chains. I reached out again and arranged an interview with Thây in Batesville. But Thây became ill during the trip, and much of the tour, including the Mississippi leg, was canceled while he recovered. It wasn’t until a conversation with a nun during this year’s trip that I learned just how ill he had been: she brought up the illness in a conversation in which I had asked about what the organization and the work will look like after Thây’s death. She spoke of the roles various nuns and monks took on in his absence.

Thây is 87 now. And when I sent an inquiry in late summer this year, having learned of another U.S. trip by the Zen Buddhist teacher, I received generous notes in reply that ultimately said, with regrets and a sincere lotus of peace, that because of his age Thây’s schedule is much more restricted now, and he could no longer be made available for an interview with me. But would I still like to visit Magnolia Grove Monastery and experience the Healing Yourself Is Healing the World Retreat?

I was invited to come and, specifically, to interview Sister Chan Khong, whose work has been so critical to the organization and who is a powerful dharma teacher in her own right.

I said yes, of course. So, one day in late September, I joined the retreatants in attendance on the beautiful Magnolia Grove grounds for Thây’s morning meditation, his dharma talk, and his walking meditation. I participated in a dharma discussion and sharing, attended a beautiful deep relaxation session in the meditation hall, and listened to a presentation about bringing mindfulness practices into schools. And I had a chance to speak one-on-one with several of the sisters, including Chan Khong.

Here, in what’s meant to be simply an interview excerpt as a blog post, I won’t attempt to offer a full biography of Chan Khong — better for you to read this 2012 article by Andrea Miller in Shambhala Sun or, better still, get hold of Chan Khong’s autobiography, Learning True Love: Practicing Buddhism in a Time of War. But, suffice it to say, her good works in helping the poor, the desperate, and the hungry, in times of war and in times of peace; her advocacy for social change and for peace itself; and her essential work in partnering with Nhat Hanh to promote mindfulness teachings all help to make her an especially impactful person of our time. She is 75 years old — she was born in Vietnam’s Mekong River Delta in 1938 — and she began working alongside Nhat Hanh fifty-four years ago, in 1959.

Chan Khong — her monastic name, which means “True Emptiness” — is described by Thây, in his foreword to her book, in this way: “True Emptiness is also true love. Her story is more than just the words. Her whole life is a dharma talk.”

This little excerpt elsewhere in my interview with Sister Chan Khong is referred to in the longer response I’m sharing:

When you look at me, you have a perception about me. But your perception is only partial. Yesterday in the sharing of touching earth, I also shared that a main point the Buddha says is that of wrong perception: Everyone has a perception, but most of the perceptions are wrong. Eighty percent, ninety percent are wrong.

You only perceive one part. Like a blind person trying to touch an elephant. You touch the leg of an elephant, you say that the elephant is like a pillar. Other people touch the ear of the elephant, and say that no, the elephant is flat. Pillar is correct, but only partially correct. Flat is correct, but only partially correct.

So when you are shocked by the behavior of somebody, it’s because you see only ten percent or twenty percent of his behavior or her behavior. You need to look deeper and inquire gently: Why? I thought that you must do something like that, but you did this instead, differently.

Why?

So, with that shared, here’s a little Q-and-A excerpt in which Sister Chan Khong touches upon Western suffering, where war begins, what interbeing is, and (in a section excerpted previously on this blog, as well, but helping to bring this post to a coherent, well-rounded conclusion) why we try to be beautiful:

Ray Hemachandra: Your good works have included serving the most desperate during the worst times — in war, with refugees, during religious oppression, in many circumstances when people lacked even the most basic necessities of life — and sometimes at enormous risk to yourself. Many of us, particularly in the West and myself included, live in conditions of relative plenty, yet coming from much more difficult conditions, you have dedicated yourself — your life — to serving others. It gives me pause. What are so many of us missing, do you think? And how can we do better: what are the starting points for our developing greater compassion and then taking action?

Chan Khong: In the West you don’t have very much of the kind of suffering like the bleeding of a person hit by a bomb. But in fact, if you look deeper, there is a lot of suffering, too.

There are many broken families. We see them. They come to Plum Village — fancy, nicely dressed people. But when we allow the child to come and ask a question to Thây, she sobs. She says, “I don’t know what love means. My parents say that they love each other, but then they shout at each other and they make each other suffer. And then they divorce. And they insult each other in front of their children. And I suffer so much.” These are 8-, 9-, or 10-year-old children.

That kind of suffering is in many families in the West. But you try to hide it. We know it just because your child comes and asks questions in front of people. But usually there are tragedies hidden in that corner or the other corner and everywhere.

Many little wars like that are everywhere.

So when war breaks out in Iraq, or in Iran or anywhere, that is the last drop in a number of broken relationships among Americans and among Iraqis. When conditions are mature in that direction, war starts.

Even at that moment after 9/11, Thây tried to come and explain everything [Read an excerpt from Calming the Fearful Mind: A Zen Response to Terrorism]. The New York Times, at that moment, sent this man who loved Thây a lot — every time Thây was interviewed by him, always he would write a good article — but at that moment Thây talked about compassion, about calming, about looking deeply, about listening deeply, including about why they behave in such a way that they would risk their lives. The man listened. But he said maybe it was too soon, that his editor would not allow him to publish such an article.

And so you see: Everywhere they have wrong perceptions. For the American people at 9/11: Terrorists are evil. They are demons directly from hell.

But, you know, I had a chance to speak to Palestinians who came to our retreat. They were not terrorists, but they had a brother who was a terrorist and who exploded a bomb. And the brother had written to them: “I go directly to see Allah when I explode the bomb.”

Because, for him, that was a good cause. He had a wrong perception about Americans. For him, Americans are demons who spend their money to sabotage other people’s culture — in Iraq and for all Muslims. So they have a very wrong perception about the United States. And so they are ready to kill themselves and to kill thousands of people, if they can, in order to go directly to Allah. For them, they have wrong perception about Allah, too. Because they have heard that Allah is somebody who wants them to retaliate against bad people.

But Allah is holding both sides, in his left hand, in his right hand. We have to understand the difficulty of the left hand in order for the right hand to comfort it, and the difficulty of the right hand for the left hand, for them both to complete each other. So, Allah, or God, or Buddha is embracing everyone.

Because of their wrong perception, they even told themselves they were killing for a good cause. They were ready to die because they thought that they’d go to Allah. But maybe at that moment Allah said, “No! I didn’t tell you that!”

They killed thousands of people. Why did they die?

So you see the wars are not only in the East and the West, but here we have the privilege that the big war has not exploded yet. So we have to look deep. We have to be mindful of what happens in us and the people around us to see that the war will not happen in your family, the war will not happen in your office, the war will not happen everywhere around you in order to stop the war — the big war — in the world.

Ray: Why are we here? And why serve?

Chan Khong: Why are we here in this world?

Ray: Yes.

Chan Khong: I think that it is the nature of everyone to want to be beautiful.

Everyone tries to be beautiful, even the tree, even the flower, even the leaf. We all try to be beautiful.

Unfortunately, sometimes we try to be beautiful in our ugly way, and we make people suffer.

We make people suffer — the people around us — and then you can see what the criterion for beauty is: that you have to be so other people can be together there with you — in harmony, in peace, in joy.

If you try to be by yourself, or to inter-be with many ugly conditions around you, and you make the world a mess — killing each other, insulting each other, behaving in terrible ways to each other — that also is interbeing, but in a very wrong way.

Ray: Thây spoke about interbeing in his dharma talk this morning. What does interbeing feel like to you? How would you describe it to someone unfamiliar with the concept?

Chan Khong: Interbeing is like the flower that cannot be by herself without the sunshine, without the rain, without the caring of the gardener, and without so many conditions.

So, normally we must set up interbeing — or co-being. We co-exist. We cannot exist by ourselves.

There is nothing in this world that or who exists by itself alone.

So, there’s no separate self. And that is a very critical point the Buddha tried to make for you to see. Don’t be caught by your separate self and your ego, narcissism, and greed, because you think that you are so important.

In fact, without the smartness of your father, the skillfulness of your mom, without many good conditions, you are nothing. But thanks to all these favorable conditions, you become something.

And that something is the coming of interbeing: many conditions coming together for you to be.

Source: Ray Hemachandra and Golden Moon Publishing at

http://rayhemachandra.com/

Share Your Reflections