Sister Chân Trăng Tam Muội recounts the challenges, joys, and learnings from a year in lockdown with very elderly parents.

I stood in the hallway, one hand placed lightly on the banister, and breathed slowly.

Suddenly, I heard the thumping steps of two young girls galloping and laughing up and down the stairs. I saw Dad standing in the hall calling upstairs, and heard sounds of cooking from the kitchen, Mum preparing lunch. Standing in the heart of the now empty house, our family home for sixty years, I said goodbye and left the spirits of the place to play on.

It had been a long journey. Rewind 18 months to Spring 2019. I receive yet another urgent call to come home. My father, ninety-six, blind, with failing health may be dying. Over the years I had been preparing myself for their passing and I knew the importance of “Don’t wait.” With deep gratitude for the support of the Lower Hamlet sisters, I left for England. Thankfully Dad rallied once again, but it was not to last. With the UK and France going into full Covid lockdown, I stayed on and was thus able to enjoy two more months by his side. Dad died peacefully in his own bed on a beautiful May morning with the family all around him, Mum holding his hand. Minutes after my father’s last breath Mum said, with relief, “Well, if that’s what dying’s like, it’s not so bad.”

A carer had shared with me how the family can take care of the body in a respectful and nourishing way. First, my elder sister and I requested to help the nurse mindfully and lovingly wash his body and dress him in his best pyjamas. We asked to keep Dad’s body at home for another day. I surrounded his body with fresh May flowers from the garden that he and Mum had grown and tended for over 60 years: rose petals were strewn over the bed, lily of the valley placed at his head.

To sit with his body was a wonderful experience. In England the old traditions have been lost and most people want death to leave the house immediately. The close family visited and we were able to sit around Dad and recall our happy memories to honour his life. Mum also had quiet time to say her goodbyes, so essential because they had been married for almost seventy years. When she finally decided that she was definitely going to attend the funeral, on leaving the house in a wheelchair, she was moved to see the whole street gathered to greet and applaud her.

Later when the ceremonies were completed, I had to decide when to return to Plum Village. I felt deeply conflicted because on the one hand how could I leave my Mum to mourn alone, even if she had a wonderful live-in carer to take care of her personal needs? On the other hand, as any of her carers could tell you, Mum is not an easy woman and the idea of staying with her for an extended period was, frankly, scary.

Rewind many years! At sixteen I had gladly left home for “Swinging” London, first to attend ballet school, then art school. I was a rebellious teenager; it was 1972 and I needed SPACE! Later, after my studies in fashion design, I increased the distance, moving to Paris to work as a designer. But no geographical distance was ever enough to heal the unease. I could not bear to be in the same room as my mother. However, a wholesome inner voice advised me “this is not good.”

Ten years of Freudian analysis ensued, years rich with learning and insight; the veils of misperception began to fall. But it was when I engaged with Plum Village practice in 1998 that deeper healing began, first as a lay practitioner and then as a monastic.

Practice: Centring Mum and Dad, letting go of the child’s need for the parents’ attention and instead, developing curiosity about their lives, encouraging and listening to their stories and thus validating their lives especially as they grew older. This change of dynamic completely transformed our relationship. I learnt about what had conditioned them (education, family, economic situation, the collective consciousness of their epoch) and their often challenging life circumstances as well as their joys. I experienced what Thay has often taught us, that healing becomes possible through understanding, and then compassion and forgiveness emerge naturally without effort. I saw my parents and myself as vulnerable beings, all doing our best, and a strong connection of love grew in my heart.

However, the idea of being locked down with Mum indefinitely was way beyond my comfort zone! But in meditation I gave space to a small, quiet voice that wanted to offer love and support to the only mother I have, who had cared for me as a child and also to relieve my sister who had been caring for my parents for many years, albeit from a distance. On telling my sister these thoughts, she exclaimed, “What a sacrifice!” But the only sacrifice was the intention to make caring for Mum sacred, a part of my practice. Easy to say, difficult to do! The home I had run away from, fifty years before, now sent phantoms and ghosts to haunt me. My intention was to stay present and stay put. But how?

Practice: A checklist: Am I taking care of my freshness, solidity, and joy? To my surprise I slipped into a regular daily schedule starting the day with meditation to digest and investigate the latest emotional storm which came from around and inside me. To cultivate joy, each day, rain or shine, I walked in the nearby forest where I had played as a child, taking refuge in the ancient oak trees–our ancestors–giving them a long hug. Every morning I worked in the garden, accompanied by the robins who had also accompanied Dad. Before dark, I cycled along the beautiful country lanes of Hampshire, empty now during lockdown. By Zoom, I facilitated Dharma sharing families for all of the Plum Village online retreats and supported the UK Sangha. With all this joy I had enough solidity to offer my presence to Mum.

I was also inspired by the Five Invitations of Frank Ostaseski, founder of the San Francisco Zen Hospice for the Dying, a practitioner who has spent his whole career accompanying the dying:

- Don’t wait (at ninety-eight, Mum won’t be here long, so it’s now or never)

- Welcome everything, push away nothing (this gave me courage)

- Bring your whole self to the experience (even my vulnerability, especially my vulnerability)

- Find a place of rest in the middle of things (sitting and breathing with Mum)

- Cultivate “don’t know mind” (it’s OK to not know how long I’ll be here.)

Even though Mum was frail, tired, bedridden, and very old, sometimes I felt like I was trapped with a dangerous, unpredictable wild animal. I felt like the artist Joseph Beuys who in 1974 as an art “happening” lived in his studio with a wild coyote. I allowed the old fears to gradually come up and saw that they originated from childhood, never knowing how Mum would react, or what mood she might be in when I came home from school. Later we found out that she had periodically suffered from bouts of depression. This, combined with her inability to either recognise or take care of her emotions made an unsafe and threatening emotional environment in which to grow up.

Now, towards the end of her life, Mum would often say things which were rough and hard to hear but my practice was to simply stay present, even if my heart was racing, my stomach churning, and I just wanted to run, like I had always done in the past.

Practice: After coming back to my breath and feeling the earth solid under my feet, I would imagine what she might be feeling and reply, “Are you angry? Or tired? Or frustrated?” and to my amazement she would pause and then agree, “Yes, I am angry …” and we would be able to slowly talk it through, carefully putting her strong emotions into words. In a short while, calm was restored, hands held, a hug. It was as if I were lending her my nervous system. I was stunned, we had traversed a difficulty that when I was a child, would have caused her to stop talking to the whole family for several days. For a child these were violent and frightening periods of silence. As a child, I would think “It must be my fault, I must be bad.”

Practicing self-compassion for having safely navigated the latest emotional challenge, I took care of my inner child, hers and mine, both of whom had certainly suffered from emotional neglect, though not with intention. I felt compassion for Mum’s frustration, how much she must have suffered through her incapacity to communicate. I felt deep gratitude for Thay, who has enabled me to become my own loving parent. Breathing in, “May I allow Mum to be exactly who she is,” breathing out, “may you, Mum, feel safe, may you live and die with ease.” And then I would remember to congratulate myself, tapping myself on the shoulder, saying “Well done, Tam Muoi, survived again!”

One of the highlights of my stay was finding an old box containing 200 letters that Dad had written to Mum when he had TB. He was diagnosed just five years after they married, and my mother found herself alone taking care of my three-year-old sister, far from any family members. He wrote to her every day even though Mum visited him twice a week! I offered to read the letters to her, although I felt nervous entering into their intimacy. But she replied, “Oh yes, then he will be here with us.” So after each meal, I would read a few letters. It was a real gift, to discover the sensitive, affectionate man who could write so tenderly. It was lovely to read his enthusiastic dreaming of “another infant” (me!) and of his love for my sister, for whom he made wooden and basketwork toys whilst in the sanatorium.

My “No Escape” retreat would not have been possible without the support of many carers and nurses who were coming in and out throughout the day. We had two principle live-in carers who alternated, three weeks on, three weeks off, Charity from Essex and Zimbabwe, and Marian from London and Uganda. It was a real privilege for me to share my life with these women, supporting each other, or dancing round the kitchen as we cooked together. Not only are they excellent professional carers but we became friends, supporting each other through Mum’s ups, but particularly her downs. Many times, I or they would come back to the kitchen having been roundly scolded by Mum, and we would be there for each other with a hug or a hilarious reflection to bring back a smile. As they shared more about their lives, I was humbled by their capacity for joy, sacrifice, and resilience, especially as they navigate the challenges of being Black in Britain.

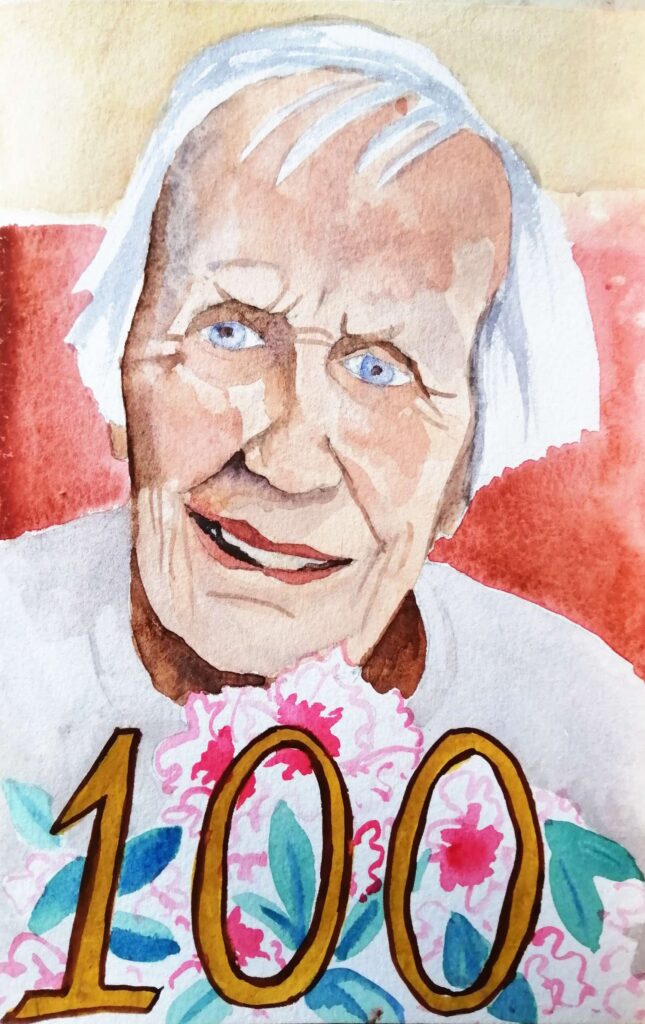

Seven months on, it seemed that Mum was not going to die a few months after Dad (as everyone had thought), and that she really had her eye on getting to a hundred (like her cousin Edith), which was still ten months away. I started to think about returning to Plum Village. I had a dream where I was making a delicious meal. I opened the lid of the saucepan to check on the dish and happily exclaimed “It’s cooked!” Waking up, I felt a deep sense of fulfilment that lasted for several days. I felt I was cooked, it was time to go home.

Fast forward to two weeks after Mum’s very happy hundredth birthday party. My sister urged me to phone Mum. On WhatsApp I saw Mum’s beautiful face, tired now, eyes half closed, no longer needing to speak, but smiling as I expressed my love and encouraged her to let go and take a deep, long, much deserved rest. She never woke up, she died in her sleep that night.

The day before her funeral, I was able to sit a long while with her body and place a bouquet of flowers in her hands. This is the poem that came to me, which I read out during her service.

Contemplation on Mum’s body Your two hands Now folded in peace upon your chest Were once working tirelessly. Caring for family, caressing a child’s feverish brow, Laundering, chopping the veg, Making the tea. Or typing furiously, Or with hands plunged in warm earth Tending your beloved garden. Now, fingers and joints are gnarled like the ancient oaks of Sheet. Crooked feet, once strode boldly across fields And lightly skimmed the dancefloor in the arms of Dad, quickstepping. Barefoot, we wandered together through Indian temples And hand in hand, paddled along the English shore. Breasts, become flat and empty, Once plumply suckled two tiny infants Whilst you sang to them sweet lullabies of love. Your eyes, clear and twinkling of Wedgewood blue, laughing. Gazing on the Queen’s card received for your one hundred years lived fully, You said “I am so lucky!” Now, your body like old leaves of tea, Used up and discarded. But we, amongst many, Have drunk your tea, your essence. You are in each one of us. We are your continuation.

Epilogue

As we emptied the house, my whole life was unravelling before me, held in old photos and worn objects, loved and well used. Each cupboard, box or tin opened, more treasures were revealed, and then in their turn, let go of.

Waking on the morning of leaving for Plum Village, I felt a deep sense of closure. My parents once more together, their ashes buried in Sheet village churchyard. All is well.

Share Your Reflections