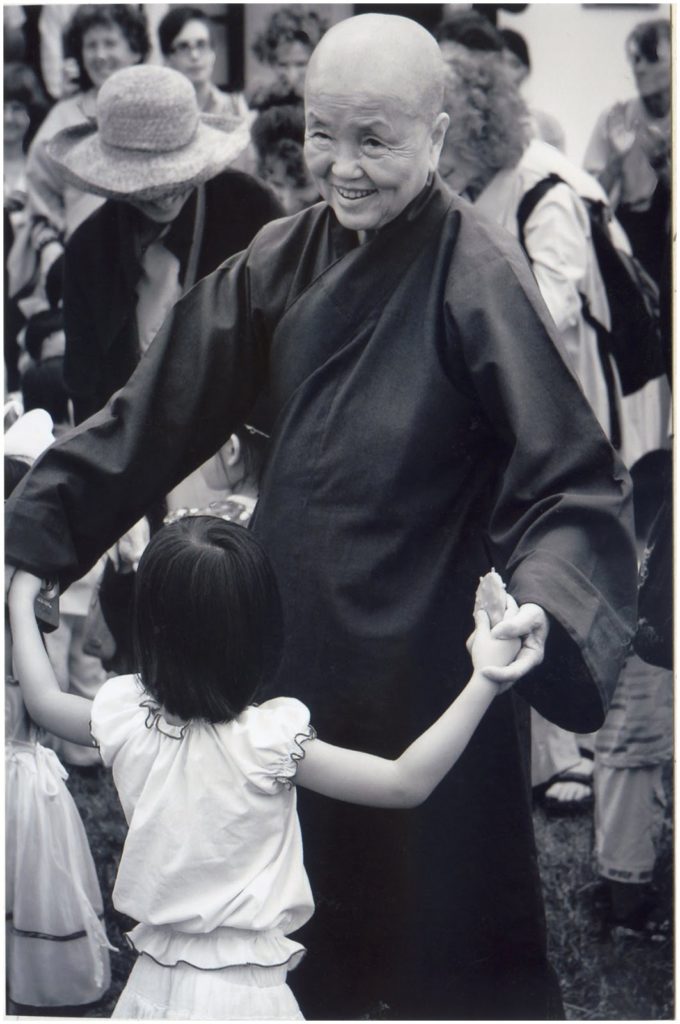

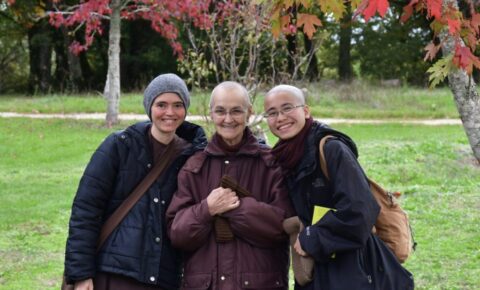

Nowadays, we would probably call Sister Chan Khong a social activist. An encounter, in the middle of the Covid-19 crisis, between Buddha News and a Vietnamese Zen Buddhist nun who for 60 years has been campaigning for social and spiritual change.

When you were very young, you worked to help the poorest in the shanty towns around Saigon. Where did this desire to be active in the social field at such a young age come from?

From very young, I always wanted to help others. Perhaps it was linked to the fact that I was brought up on the words of my paternal grandfather, who was very respected in his community, who constantly repeated to his grandchildren: “We have no money to leave to you, but we will bequeath you the merit we have accumulated by helping people in need.” My maternal grandfather also made a great impression on us by his actions. When it was cold, he would ask us to go and visit homeless people and to bring them straw mats and warm clothes. He also encouraged us, several times a year, to make meals to take to people in prison. In my family, I always saw my mother and father, like solid oak trees, looking after many of their nephews and nieces, as well as their nine children. My mother would also make small loans to poor people in our community so that they could start a micro-business and live from their earnings.

Was your first meeting with Thich Nhat Hanh, in 1959, a turning point?

I must have been a Buddhist nun in past lives. When I read my first book about the life of the Buddha, I immediately felt I had found my path.

When I had the opportunity to hear Thich Nhat Hanh speak for the first time, I was very impressed. What he said moved me in the deepest part of myself. He was the master I had been waiting for for a long time. His teaching was so profound. He has devoted his whole life to awakening us – he has constantly urged us not to live like automatons.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s ideas went far beyond traditional notions of charity consisting in providing food, medicine and money to the poor. They aimed to help the poor country people improve their living conditions themselves without having to ask for outside help.

When I met him, I was dividing my time between university, where I was studying biology, and social work in the shanty towns. I coordinated around 60 young university staff and students who were working as volunteers to help to improve the lives of homeless people around Saigon. Thich Nhat Hanh shared the same social ideals, but he also wanted to work for peace. When he learned that I had set up a team of some 70 people to do social work in shanty towns around Saigon, he thought straightaway that I could help him in his social mission to promote a form of engaged Buddhism.

Thich Nhat Hanh insisted that the social action that you carried out together during the Vietnam War should have a spiritual dimension. What does social engagement underpinned by a spiritual dimension look like?

At the School for Youth for Social Service that we set up in 1965 in Vietnam, there were initially 300 young people who volunteered to help the poorest in society. Thich Nhat Hanh’s ideas went far beyond traditional notions of charity consisting in providing food, medicine and money to the poor. They aimed to help the poor country people improve their living conditions themselves without having to ask for outside help. He wanted to promote the idea that social work and rural development were means for personal and social transformation. By the end of the war, 10,000 volunteer social workers were working alongside us. Without a spiritual dimension, actions carried out at first with compassion and deep insight end up resembling projects of a commercial enterprise. If our work is devoid of any spiritual dimension, we risk gradually losing sight of the purpose of our actions to help others.

In your book “Learning True Love”, you describe a humanitarian expedition during the Vietnam War, in the middle of fighting and gunfire, and “a kind of magnetism, the energy of goodness” that protected you from the bullets. Could you describe this in more detail?

If you are a Christian, you call on God when you are in distress. Buddhists call on the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. In 1964, we organised an expedition to take provisions, clothes and medical supplies to poor people in a region at war that had been ravaged by floods.

We had to cross combat zones caught between fighters from the two sides – the communists and anti-communists. I said to the friends I was with that we needed to call on Avalokiteshvara:

Avalokiteshvara, I allow you to borrow my body, my arms and my hands to carry out this mission.

When you let go and allow him to act in your place, your fear dissolves. And danger moves away from you. Sitting in one of our five little boats, I started to recite the Heart Sutra, while the bullets whistled around us. I was sure that the bombs, grenades and bullets wouldn’t touch us – warriors of love that we were – as we would be protected by Avalokiteshvara.

All of a sudden, we couldn’t hear any more gunfire. Compassion had prevailed.

We continued with our mission, in religious silence, coming to the help of the wounded on both sides.

Different times, different crises. What initial lessons might you draw from the Covid-19 pandemic, which seems closely linked to the environmental crisis?

This pandemic is the result of a spiritual crisis. I’ve heard Thich Nhat Hanh say of the earthquakes and other tsunamis in recent decades, like the one that happened in 2004 in the Indian Ocean, that it is a reaction of self-defence by Mother Earth, furious about the squandering of resources, pollution and destruction inflicted on her. We only have one planet. We shouldn’t forget that, over the course of history, great and advanced civilisations have died out suddenly. The coronavirus crisis is an extremely important signal that has been sent to us: the signal that we must stop destroying the Earth. At the same time, as this health crisis has unfolded, forms of discrimination have multiplied. We need to learn how to love as the Buddha taught us in the four elements of true love: we should bring happiness and kindness to others (“maitri”), relieve suffering (“karuna”), cultivate joy and benevolent and altruistic love (“mudita”), and also the steadiness of mind that is known as equanimity or inclusiveness. This period of lockdown has been a chance for women and men who in normal times are too taken up by their work to come back to themselves and reconcile themselves with their bodies and minds. It is giving us an opportunity to put a stop to the flow of thoughts which too often carry us away, and to devote ourselves to spiritual and physical exercises, in peace, with a smile on our lips. Freed from these invasive thoughts, our thinking will be deeper and clearer. This is what we call deep looking in Zen Buddhism. As we calm ourselves, clarity of mind appears.

This is a moment to devote more time to your loved ones, to your family. A time to pick up the phone to tell those who are far away that you love them and care about them.

Interview by bouddhanews.fr, translated from French by S.STRACHAN

Share Your Reflections