Welcome to episode 77 of The Way Out Is In: The Zen Art of Living, a podcast series mirroring Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh’s deep teachings of Buddhist philosophy: a simple yet profound methodology for dealing with our suffering, and for creating more happiness and joy in our lives.

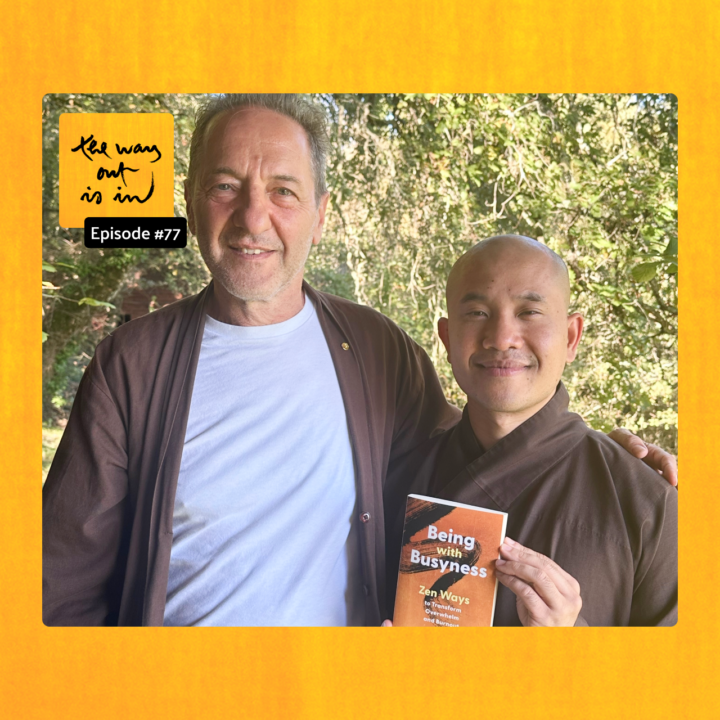

This special episode – part one of a two Q&A installments – marks the launch of the first book by Zen Buddhist monk Brother Phap Huu and leadership coach/journalist Jo Confino. Being with Busyness: Zen Ways to Transform Overwhelm and Burnout is intended to help readers navigate these experiences, relieve stress, and reconnect to their inner joy through mindfulness and compassion practices inspired by Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh.

Instead of discussing the book, the two presenters asked listeners to submit their questions on these timely topics. Listeners’ generous, vulnerable questions answered in this episode include: Can mindfulness help us observe busyness, set limits, and let us savor boredom and solitude? How do you handle the phone as monastics in Plum Village, and what do you do to not get pulled in? How can I make long-lasting change when our culture demands constant attention? How do I survive when I desperately want to leave my line of work but can’t for financial reasons?

Co-produced by the Plum Village App:

https://plumvillage.app/

And Global Optimism:

https://globaloptimism.com/

With support from the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation:

https://thichnhathanhfoundation.org/

List of resources

Interbeing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interbeing

Being with Busyness

https://www.parallax.org/product/being-with-busyness

‘Three Resources Explaining the Plum Village Tradition of Lazy Days’

https://plumvillage.app/three-resources-explaining-the-plum-village-tradition-of-lazy-days/

Dharma Talks: ‘The Noble Eightfold Path’

https://plumvillage.org/library/dharma-talks/the-noble-eightfold-path

Online course: Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

https://plumvillage.org/courses/zen-and-the-art-of-saving-the-planet

Bodhisattva

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bodhisattva

Christiana Figueres

https://www.globaloptimism.com/christiana-figueres

Quotes

“The title, Being with Busyness: it’s not getting rid of busyness, it’s not fixing busyness, but it is a way of being with busyness. But it’s not about fixing it, it’s about how to be in it and how to be with it; how to move through these particular strong energies of our society so that we don’t lose ourselves.”

“The first wing of meditation is the art of stopping and recognizing the present moment. But there is a fear of doing nothing, because we have been educated – dare I say, brainwashed – to think that we have to do something in every moment of life, because time is money. Time is projects; time is to succeed. And this has driven our society into a mindset of not knowing how to be in the now.”

“Thay always reminds us that the purpose of being alive, first and foremost, is to be here, to know what is happening in the very here and now.”

“Knowing that we have habits that are taking us away from the present moment is already mindfulness.”

“A mindful life, the art of mindfulness, is not about just cutting off bad habits; it’s also about developing enough good habits to replace the bad ones.”

“I really love this idea of reciprocity: the idea that if you’re given something valuable then the most natural thing is to want to give something valuable back.”

“It’s not about the laptop. It’s about how we use it; it’s about what kind of practice we build around it.”

“There is a system pushing us to be a certain way. There is a system making demands of us – but, actually, within that system we always have agency. There is always something we can do.”

“Dwelling happily in the present moment doesn’t mean that that moment needs to be happy for us to be happy – but it is about being happy no matter what.”

00:00:00

Dear friends, welcome back to this latest episode of the podcast series The Way Out Is In.

00:00:08

I am Jo Confino, working at the intersection of personal transformation and systems evolution.

00:00:28

And I’m Brother Phap Huu, a Zen Buddhist monk, student of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh in the Plum Village community.

00:00:34

And today, brother, we are recording a special episode and it’s to mark the launch this week of the first book we have co-written. And the book is called Being with Busyness – Zen Ways to Transform Overwhelm and Burnout. And the reason we decided to write that book is because so many people that we meet or work with both for you, Brother Phap Huu, in the monastery, and for me through my coaching practice, people are suffering from taking on too much and not being able to cope. And so we felt this is such a societal, it’s an individual and a collective issue and people are suffering from it so much that a book would be a wonderful gift to help people to alleviate their pain and suffering but also to find very practical tips on how to find ways through this difficulty.

00:01:34

The way out is in.

00:01:58

Hello, everyone. I am Jo Confino.

00:02:00

And I’m Brother Phap Huu.

00:02:02

So Brother Phap Huu, the sun is shining. We have 10 days of good weather ahead of us which is… I feel very petted by the weather actually. It’s like I’m sitting outside and I think oh, thank you, nature. Thank you for looking after me. I feel like I’m being massaged by the warm weather. So how are you at the moment, brother?

00:02:25

It does feel that way. It feels so nice to have sun for the coming days because it has been a very wet year, it’s been raining so many months and this is very unusual for our climate that we’ve experienced throughout the years here, in southern France. And on a practical level, as a community in Plum Village, we do so many things outdoors so having sun is such a great support.

00:02:55

Yeah. And actually it allows us to be in nature which is of course one of the wonderful antidotes to busyness. But brother, back to the book. So how do you feel about having written your first book?

00:03:12

Well, first of all, I think I feel very grateful just to have the opportunity for something to manifest, like a book. And how wonderful it is to not be alone and it’s shared with you. And I really have been just paying homage to Thay, our teacher, and then to all of the spiritual ancestors that have been before us in the Zen tradition, in the Buddhist community, and in the spiritual world of teachers who have transmitted so much. And I really do feel like there’s a part that is us but there’s a part that is beyond us also in this book, so I feel grateful. I feel scared a little bit of people’s judgment, people’s reaction and I think that’s just a very natural human tendency to have these particular fears and it’s because I think it comes from a lot of care and hoping of the intention that people will receive it as a way of not fixing all the problems but also just seeing a different way of being. And the title itself is saying being with busyness, it’s not getting rid of busyness, it is not fixing busyness, but it is a way of being with busyness. But because in our way of thinking today, even when I was like contemplating like the perception of what people will be receiving this book maybe they’re looking for a way to fix this. But I have to remind myself that it’s not about fixing it but it’s about how to be in it and how to be with it, how to move through these particular strong energies of our society so that we don’t lose ourselves. So a lot of practice in this moment, Jo. And how about you?

00:05:11

Oh, well, you know, very similar to you, brother. There’s something, you know, I could not have written, help write this book without Thay. And Thay could not have created his teachings without all the generations and then back to the Buddha, 2600 years ago. And so it’s a sort of, it’s a really a sort of a homage and appreciation to everyone in my life who has given me, you talk about generosity, has given me generously their time and love and attention and wish to live a good life. And so this feels like, you know, I really love this idea of reciprocity. The idea that if you’re given something valuable then the most natural thing to want to do is to give something valuable back. So this feels like a very small gift in return to an enormous amount of kindness and love I’ve received actually all through my life. So brother, what we did we thought rather than us just say what we want to say, which is sometimes the case that we would we’ve done a few question and answer sessions and we thought this was very relevant actually so rather than just talk we would ask for listeners questions so we put out an Instagram story and ask for questions. And we’ve received a really beautiful selection of questions. And very generous, you know, there’s, as you mentioned a bit earlier, brother, there’s a real generosity and vulnerability in these questions. That you can tell that within the questions there’s a real heartfelt desire to find a way through the thicket and complexity of life and to come back to a place of balance and calmness amidst chaos. So what we’ve done is we’ve sort of, in a sense, ordered these questions and sort of brought them together in themes. So for those of you who may feel your specific question has been answered hopefully in the way we cover these themes and the way we talk about this that that your question will be within that and throughout this podcast and the podcast series we see interbeing at work, that actually in each individual question are all the questions. And all the questions is one question. So brother, I would thought, I’ve got them in front of me on my screen, so I thought maybe what we should do is I will just read out questions and then you can kick off and then I can sort of join in with any extra thoughts. So I love this question and it’s about allowing the opportunity and space to be bored, which I love. And so the question is this, I’d like you to talk about the fact that there is a certain dependence in our journey to always be busy. There is no day of the week where not only adults but also children constantly have activities of all kinds. Are we afraid of getting bored? Can mindfulness help us observe these mechanisms, set limits, and let us savour boredom and solitude? Such a great question. And before I pass it to you brother, I always remember my older son once, when he was about 13, coming to me and saying dad, I’m bored! What should I do? And I said, allow yourself to be bored. That actually in our boredom there actually what it’s showing us is space and if we actually go into our boredom and we can move beyond this thing of oh, no, what should we do, but actually how can I observe myself in this moment and what it can show me, what can it unveil for me. So brother, over to you.

00:09:20

It is definitely a modern mentality that we don’t know how to do nothing and therefore, ironically, our teacher, the founder of our traditions, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh, he selected Monday in the community, which is the day where everybody gets back to work or gets back into a busy rhythm in society, he chooses Monday in the monastery to be a lazy day, a practice of doing nothing. And he has explained that our times and our way of thinking is to always to do because we see time as a foundation of doing. And therefore this particular mindset it always pushes us towards the future or it pushes us towards getting or consuming or running away from the present moment. So it’s funny because the first wing, as in like a wing of a bird in meditation is learning to stop, learning to be in the moment and knowing what moment it is and having the capacity to just identify what is my state of mind right now. Am I neutral? Am I excited? Am I happy? Or am I sad, am I lonely, am I anxious? So the first wing of meditation is literally the art of stopping and recognizing the present moment. And there is a fear of doing nothing because we have been educated, we have been, in a way, dare I say, brainwashed, that we have to do in every moment of life because time is money. Time is projects. Time is to succeed. And this particular way of thinking have driven our society into a mindset of not knowing how to be in the now. And our teacher, Thay, he says… Thay means teacher in Vietnamese, Thay always reminds us that what is the purpose of being alive? First and foremost it is to be here, to know what is happening in the very here and now. And that is scary because when we allow ourselves to really be in the here and now, our mind is not being stimulated, our senses are not being drawn away from the reality of the now and that boredom that we think is boredom, which is the space of nothingness or the space of silence or of allowing us to feel, suddenly we have to be in touch with, in the boredom, our suffering. I think this is what a lot of people are afraid of. And this is what I am afraid of that comes up in my day to day moments when I recognize I’m going to have 45 minutes or 30 minutes of free space. And how many of us like wish for those moments, we’re like, oh my gosh, I’m so busy. I just I’m craving just a little bit of me time. And then suddenly you have me time and we don’t know what to do with it. And because we don’t know what to do with it, our fear comes in, our ancestral habits of suffering also arises and then suddenly we want to distract ourself right away. Because we don’t have the capacity to hold, we don’t have the capacity to hold on to these particular present moment feeling. And so, the art of meditation and the art for us, meditation, right now, I speak of it as something to achieve but for us, as a practitioner, is literally a way of being. A meditator will know how to be in that moment and will know how to see the preciousness of doing nothing. And in the action of not doing, if we know how to not do in that moment, we can enhance our quality, let’s say, of breathing, our quality of resting, our quality of not doing anything, of allowing boredom to be the new hip, you know, the new fun, the new relaxation, the new joy. And so it’s really like changing our way of looking at boredom. And first and foremost what we will feel in boredom is this energy of uneasiness, it’s restlessness that arises because we haven’t had this art of doing nothing. And when we learn to do nothing, insights in the present moment will arise thanks to the moment of stopping that we can enter into it becomes a foundation for us to have clearer actions, more intentional action, action that is not being pushed by what people want from us, what we are striving for maybe because of our complexes, our own desire to run away from ourself. And so all of these external forces that are baiting us into doing, suddenly we have a common lake that reflects things that we can see more clearly in our life of what I need to do, what I don’t need to do, what I can allow myself to be. And suddenly then our non action becomes a foundation for our action. So with this insight, we can see boredom as a new foundation, as a way of resting, a way of seeing, a way of being. And suddenly you change the peg of labeling this moment of there’s nothing to do, How bored am I now? Instead of oh, there’s nothing to do, I can rest. And part of the art of looking deeply, which is the second wing of meditation, so we have stopping on one side, and then we have looking deeply on the other side, which is to allow us to have understanding and clarity and insights. And the insights maybe have always been there, but suddenly it becomes a life for us now. And there’s one example that Thay introduced to a lot of people in the cities because we all drive. And every time we see a red light we have to stop. And in that moment there’s nothing to do, you can’t move forward. If you do you break the law, you get a ticket. Right? But in that moment of sitting there in front of the stoplight you have an opportunity. What are you going to do? Are you going to enjoy breathing? Are you going to enjoy just looking at the surrounding? Are you going to see another car beside you and, I don’t know, offer a smile to that person? So there’s so many things that can happen in that moment. So this question really, you know, is really asking for a collective society like what is it that is pushing us away from being and doing nothing? And recently just before this podcast I shared with all of you what I just read as one of the technology developments is like they’re testing out 6G now. So, apparently, we have 5G now.

00:18:03

Haven’t seen it.

00:18:04

Haven’t seen it. I feel like the maximum we get is 4G here. Right?

00:18:08

On a good day.

00:18:09

Yeah, on a good day. And now it’s 6G. You can download under one second 938 gigabyte or something like that. And then the description of attaching us to it is it explains imagine you can download 50 gigabyte of a blue ray movie under one second. And you can see the advertisement or the bait that attracts us is like oh, with the speed, we can have more to consume. And then it was our friend asked isn’t it crazy how much we just want more and more and more? Even though 5G is I think incredibly fast, which we don’t…

00:18:59

We can only imagine.

00:19:00

We can only imagine. We’re still at like… we’re like two years behind in the Upper Hamlet here with this technology. But it’s incredible just to see the wording, the formulation of why we need this intense speed now. So that’s a representation of our humanity.

00:19:48

Brother, there’s so much in what you just said. And one thing I just want to reiterate in a sense, focus on, is that firstly the word boredom, we should find another word for it. Because it’s not actually boredom. Boredom is an excuse to act but actually it could be rest or renewal or sort of… or probing, or sort of waiting, or, you know, there’s so many ways. But for me it touches into our creativity and to channel sort of whether, you know, I sometimes use the word grace and I don’t know what that is, but there are forces outside of us that when we’re always busy, we’re just, in a sense, focused on ourselves. And when we open that space, we allow something to come into us. And whether that’s the voice of our ancestors, whether that’s a greater spiritual force beyond us. And it really allows us to see the world differently. And I’ll give you a couple of examples. So during the pandemic I was in lockdown in a very small town in Mexico. And you talked about stopping and deep looking, so in this town… it was shut down, so I could only go walking in this sort of desert-like scrub every day, and I went walking for four or five hours. And it was just slowing down. It was a long deep meditation and I took photographs of little insects or twigs but in a very creative way, and that was deep looking. And I learned so much about life from just watching nature, just being present to what you were saying, in the present moment I’m present to life. And then life can show itself to me and it feels like we go round in life with a veil and the veil is almost like a mirror. It’s like we look into the veil and we see a mirror image of ourselves. We’re constantly, in a sense, looking at ourselves but when we take the veil off we can actually see life. And one other example, when I was working at The Guardian, in London, I used to travel an hour and a half each way to work from Brighton, on the south coast. And I hated sitting on the train because I was bored. And I’d always, I had my phone, I had my iPod, which it was then, I had my computer, I’d have a book, and that one half hours would be filled up because I didn’t want to just sit there and be bored. And one afternoon I was interviewing someone and I was going to go back to the office but I couldn’t go back because it went, on so I went straight to the station. And I had nothing on me, no phone, no nothing. And I just sat on the train and I just looked out of the window. And in that hour and a half an idea came to me. It felt like it came out of nowhere. And that became a major project that I did at The Guardian for 12 years. And for me I know that if I’d been on my phone, if I’d been listening even to music which looks like it’s relaxing but it’s still filling your mind, if we actually clear our mind, then we have the opportunity to see things differently, and to see things that maybe would never notice before but maybe are waiting for us. And I feel so much in life that things sometimes are just waiting for us and when we open our eyes and see it we can connect to it, but when we’re looking the other way we will never see it. So some of these questions of course will feed into other questions but here’s one. And this is about how to transform habits of distracting ourselves in order to avoid our pain and you’ve already touched on this, brother, but let’s go a bit deeper. The question is… Actually there were a couple of questions. Something that I’m interested in hearing about pertains to the way that we develop deep deep habits of auto regulation or buffering as it is sometimes called. Ways that we continuously distract ourselves to escape or manage painful feelings. At its extreme, this manifests as addiction. How can we aid in retraining ourselves when some of these behaviors and habits have been with us for years or decades? And brother, you know, before I pass it to you, you know, this speaks of also the problem that that our habits have been ingrained over decades but then we want to solve them in minutes. And so how do we actually, when things are so deep ingrained that we don’t even know that necessarily that they’re running our life, that they’re sort of it’s like a software system that’s managing our life and we’re not even aware of it. How do we start to approach that? And start… because the secondary title of our book is Zen Ways to Transform Overwhelm and Burnout. How do we… What are the Zen ways that we can actually start to first of all recognize this and then begin the lifelong process of transforming?

00:24:56

I love that you said it’s a lifetime process.

00:24:59

Or maybe lifetimes.

00:25:01

Lifetimes. Life after life. And in a way we are transforming lifetime after lifetime because we’re a continuation of our parents, of our ancestors, of our society, which we have also receive these habitual actions or these ways of taking over our daily routines. So I think the first thing that I want to share is first of all knowing that we have habits that are taking us away from the present moment is already mindfulness. So we are already seeing that there is a route to particular actions that doesn’t bring us balance and well-being. And very interestingly as human beings even though we know suffering, we like suffering too. And this is where the courage and part of the path of a noble life in the eight noble path is understanding our right diligence, which is understanding that we have all of these qualities in us, or these seeds, mental formations. A formation of being able to be aware that is we have a seed of mindfulness. We have the seed of being in peace. We also have the seed of anxiety, the seed of fear, the seed of jealousy, of overworrying, of laziness. We also have extreme seeds also to go beyond our limits. Right? So a meditator would take time to sit and do nothing, back to the first question of boredom, but using boredom to sit there and actually start to feel what is the most alive energy in us right now. And it’s like having a pulse, or having a feeling of our pulse like how fast is our pulse beating in this moment? Like an Eastern doctor they would put like two or three fingers on our wrist to feel the pulse of our body. And a meditator, in a way, we want to hear and to feel. Feeling to heal. We cannot fix and we cannot unlearn if we don’t feel. And a lot of our way of stimulation is to numb ourselves. And here we want to intentionally give ourselves space and time to reflect the second wing of meditation. We have done homework as a practitioner, as a monk, as a nun. We would write down habitual energies that we see, that are so strong in us. And then we can go deeper into the habits of not just naming it and then seeing its roots. One of this roots, on a daily basis, where is it watered? When I have a particular conversation I know exactly what seed it waters. So I think this one is very universal. It’s a really sad one and it’s a little bit mean. It’s we love talking bad about other people because it makes us feel better. And like being very real, in the community, we do this too. You know, like we can say, oh, my God, did you see what that brother did that day? And then you can name all of the negative qualities that that person have. And you just feel so much better. So that is not in accordance to our right speech. Right? We even have a training that if we are to speak of someone’s fault we learn to speak to them not behind them. But for example, this is a habitual energy. And on days when you feel less than, you feel inferior, there’s a habit to then start a conversation and to talk bad about someone, a community, about the governments, about the world, etc. And it’s just a pathway of us in order to cope with the fear and the loneliness of this moment. So writing down particular habits and seeing its roots and just to understand that just to go aha, wow. These are the patterns that I have accumulated and I have cultivated also. And then when you start to see it, that is already healing in one sense because you’re acknowledging it. And then the second act of a practitioner is intentionally saying ah, when I see this energy arising in me, I will not continue to water it. I will intentionally not enter into that conversation or initiate that conversation. And that is a training. So in our language, monastics, we have precepts. They are our guards that help. If we continue to do these actions, they would lead to suffering. But our teacher uses the word of training, mindfulness trainings. So here is an example of seeing habit, recognizing habit, seeing its roots, and then intentionally making a vow in a way, making a commitment to not be controlled by our habits. But then, the other side, is then we have to find a replacement. This is the key. So we have negative habits and we have wonderful habits that we can cultivate in our daily life. So a part of a mindful life, the art of mindfulness, it is not about cutting off just the bad habits, but if you develop enough good habits they will replace your bad habits. So that’s another way of looking at this. So there’s some deep work that we can do for ancestral and also continuation. And then there is something that not maybe like we don’t have that strength yet to recognize these strong habits and transform them right away because they have been transmitted maybe for generations. But what we may, can do is creating new habits that are wholesome, that are enlightening and inspiring and adding another layer to our present moment. So like our teacher once said, and this was like, you know, for the younger generation, like when we had CDs, now it’s all streaming sites. Right?

00:32:28

I remember a lot of technologies before CDs, brother.

00:32:31

Right, right. Cassettes, and then even like a mini disk and a floppy disk. But our teacher used to say like if there’s a song, an album that you keep playing and you know it’s not wholesome, what is it stopping you from changing that CD? So here he’s introducing also like you have the ability to change and to select something else to do in that moment. And it can be so simple, Jo. A meditator, a practitioner, we have a choice in every every moment that we meet whether it is a habit energy that is suffocating, whether it is a moment of feeling overwhelmed, in that moment we can totally be caught up in that storm and we can drown in it. But what we can do is we can pour us out literally by stepping outside of our door, seeing the blue sky, seeing the tree in front of us. So very interestingly in Zen, a lot of our culture in the monastic world, in the Zen tradition, physical labor is very much part of our training. Because overwhelm and this habit, they all carry a fuel and energy. Instead of letting that energy become our main source of energy in that moment, we now direct this energy to a new receiver. And this can be our physical action. That’s why we have Zen gardens that are cultivated in the Zen monasteries. And that’s why a lot of monastics are gardeners. They learn to take care of a plant. They learn to take care of something beyond them. So it’s not about running away but it’s about focusing our sources of energy into new locations that can give us back also energy. So overwhelm, anxiety, fear, even burnout, even tiredness, our teacher actually would teach us when you’re so tired and you feel like you don’t want to do anything that’s actually when you need to get up and go sitting with the community because you can also tap into the collective energy. So yesterday I had a very packed day and my day didn’t end until nine thirty p.m. because at seven thirty p.m. even though I had to give the Dharma talk in the morning, and then all of the following activities with the community and then a board meeting at three to four forty five. Then journeying back to our hamlet and at seven thirty being ready to be on Zoom for our live opening of one of our new cohort of Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet course. And we had eight hundred seventy five people online and I was really tired. But I showed up and I allowed myself to be reminded that I can tap into the collective energy in this moment even though through the Zoom. And when we finished the session, at the end, we had our little debrief just before we all said goodbye to the monastic team and the admin team. And I literally said I feel so energized right now, I feel that I can give another Dharma talk for two hours. So it’s really interesting that sometimes we may feel that we need to rest, in a way, but maybe our skillfulness in resting is not, it doesn’t add to more energy, it can drain us, it can even pull us into a deeper slump of laziness. And this laziness is not the equivalent to a lazy day of the art of being, but it is one of the hindrance that we learn in Zen, it’s that we have to recognize our energy of not doing also and being powerless to the moment. So here, we can also see how can we change our habits with new activities. And one time a parent asked our teacher Thay, how can I encourage my children to not be so attached to their video game. And Thay said, be there for them. Simple as that. Make an activity that is fun for all of you. Have a conversation with him or her or they. And don’t keep ignoring them. Because you keep ignoring them then they need a source to take over their boredom. And that is video games. And that is different ways of consuming. So it’s literally redefining what is action for us.

00:38:37

Beautiful, thank you, brother. I just want to go back to, in a sense, what you said right at the beginning of what you said because I think it’s so important. You said people are attracted to suffering. And I remember when I was a young man, I, and someone said something similar, I couldn’t get my head around that. You know, it’s like, why are people attracted to suffering? And of course, as I’ve matured and seen the world, people actually… if people have suffered, there’s something about that’s what they feel they deserve or that’s how they feel their life is. And then they, they don’t do it consciously, but they pull that energy to them. And so when people sort of complain about being busy or being overwhelmed or, you know, any other suffering, it’s a really good question to say, what is this secretly giving me? So underneath my complaint, am I actually bringing that to me? Am I choosing to work for a boss who actually never supports me because actually as a child I was never supported? So I think there’s something also within business and burnout which is to look for the root by also taking responsibility by saying actually how is this secretly… What is the secret gift that I think it’s giving me? And gifts are normally we think about positive things, but sometimes the gift is to keep repeating the same pattern of behavior. And also, brother, I just I think one of the things we, you know, you talked about generations, and one of the things that I think really motivates people in changing their habits is to recognize that, and you sort of, you said this in essence, but just to give it a bit more texture, is that often when we change something in ourselves, we are also healing that for past generations so other people in our past, our ancestors, past generations who have not been able to deal with certain issues, that if we deal with it in our life, in the present moment, we are in some energetic way, which I can’t explain, but I feel we are easing the lives of people from the past. And more importantly, we are easing it for those in our life now and for future generations. And I find the greatest motivation for parents is when they start to see their habit, noticing their habit in their children, and realizing that if they were to change their habit or to start changing the habit or to be, as you say, to at least recognize the habit and then start to work on it, that they actually have the ability to stop it. And one of the four noble truths, you know, the fourth one is the cessation of suffering. And there’s a route to do that. And I really feel that if we act in this lifetime, we are changing the lives of people in future generations. And I find that a huge motivating force for people saying, you know, you’re not just doing it for yourself alone, you’re doing it for actually so many people around you. So, next question. Oh, this is a very practical one and I, you know, it’s like, I love it sometimes you get questions oh god, I don’t have to answer that one. So this is one of those for me. So, I feel the overuse of the phone in particular has amplified the problem of burnout and stress. How do you handle the phone as monastics in Plum Village? What do you do to not get pulled in? And this is the bit I wanted to not say, and what do you do, Jo? No, no, don’t do that to me.

00:42:40

A direct question to Jo.

00:42:41

Yeah. So I’ll answer that bit first which is badly. How do I handle it? Badly. You know, it’s the phone, it’s very pernicious for me. You know, it’s like I know that, you know, I normally charge it overnight in the kitchen. When I come down first thing in the morning, you know, to make a cup of tea, I see the phone and I feel there’s a part of me being pulled literally, almost like an energy, of being pulled to the phone. And that to not switch the phone on takes what feels like, in that moment, an enormous amount of willpower. To say, actually, no I’m not going to look at the phone, I’m going to have my cup of tea and I’m going to go and look at the… listen to the birds song in the morning, and look at the tree, the leaves of the trees rustling, etc. etc. And quite often I fail. And part of that has been, you know, that the more negative the news has been in the world, particularly for me, personally, what’s going on in the Middle East and the pain that’s causing me, is like I wake up and I feel I have to look at what’s happened. And that if I don’t look, somehow I’m absconding on my responsibility. So sometimes I feel like to look at it and feel the pain of it actually is sharing it, is sharing that with other people. And another part of me feels no, no, no, Jo, you’re indulging in pain. And actually is much better that you go and be present to life and enjoy this moment and that is a contribution. So that’s a lot, very long way of saying actually I’m not very good at it. And there are very simple methods that I’m not doing that as I speak I think I should do. So one is move the phone. So I know a friend of mine who puts the phone in a box at night and has a commitment and I do try and do this not to look after 10 p.m. and not to look before 8 a.m. in the morning. So to at least have that gap. But if I were to move the phone to another room that’s more difficult to get to, lock the door and barricade it.

00:45:00

And give the key to Paz, your wife.

00:45:04

And also having a friend, having my wife, Paz, does help me, does point things out. And it’s very important to have someone who’s there to be able to share and to say actually, Jo, maybe you could be doing this, maybe you could be doing that. Okay, that’s my… I feel like I’ve just been in a confession actually. How about you, brother? What about Plum Village?

00:45:30

Well, first of all, having a schedule is very supportive. And a lot of our schedule, it would be almost like rude to have your phone out. Like, for example, sitting meditation which is 30 minute to 45 minute to an hour, like from… that whole package of getting to the hall, sitting and leaving. And then classes that we have or Dharma talks and then walking meditation, etc. So like, in a way, what has been supportive that we’re able to keep in our tradition is like the practice schedule and the good thing is none of these practice schedule we need a phone for it. And like I said it is an invitation to go inwards and to be present with our mindfulness energy. So it is like ethically it just feels you can’t have your phone there.

00:46:33

It makes no sense.

00:46:34

It makes no sense. But ironically also that my work in the community now is as the abbot I need to have communication and so the phone is always on with me, like I always have it in my pocket. Almost. And I’m really like re-listening to Thay’s like Dharma talk about technology is like, and he said, technology is like a horse, it’s how you ride it. It is not about demonizing it and then feeling like sinful if you’re using it because now it’s a part of life and we have to accept that in a way. And for me it’s all about how do I balance the time that I’m not with my phone. So to be very aggressive with ourself about this doesn’t help because I have been very mean to myself about this, you know, like trying to have better habitual energy around it. But then the mindset of it like I am losing myself and it always comes back to like reminiscing like what I have done in the day. But now I have a different way of looking at it, it’s like, when I’m not with my phone, like how am I living very deeply? And it changes my relationship to the phone. So for example, not just in meditation, like when I am with you in a conversation and we’re sitting to have tea. And if you were to pull out your phone… like if I am to pull out my phone, like how rude is that? So I think we need to shift collectively about our attitude that we learn to respect one another’s presence and to see that the phone doesn’t have a place during those moments. So it’s like intentionally, collectively, as a society knowing when and where the phone can be and when and where it should not be. And in a way, dare I say, it’s almost like it’s not accepted because morally in you you just feel then you’re not connecting to the human beings that are in front of you. So I think like this has been really a reflection altogether as a community. And it’s a topic that one of our brothers really want the monks to talk about because it really is whatever is happening in the world enters into the monastery. Right? And we cannot also cut it off because that is too idealistic, but it’s not reality. And for us, as the path of engagement, like we have to be with a part of the ever changing world in technology. Right? Like I remember back in like my parents day like coming to retreat you had to make a phone call, you had to send in your registration via mail, like literally you printed… I don’t know where you get it, from a newspaper or something like, the registration? And now everything is online. And now you can even pay through QR codes and I mean like we have just we’ve made some very advanced step that I think that we didn’t even have time to catch up to. And it’s been a very a live topic in the community also because some like really see it as like look at it as the enemy. But then it contradicts our life, because like, yes, and how are we communicating to all the other centers is through technology. Right? So it’s a very contradicting phenomena that we have especially when you have such a strong ideal of like a well-being lifestyle. So that’s why I love like, what is our right view to it? And not to be caught in a dualistic view in it too. Right and wrong.

00:51:04

Yeah. And Thay, you know, would go out to meet all the CEOs in Silicon Valley. And his view was very much, you know, technology is a bit like money. It’s neutral on one level and what we infuse it with is what we create. And that technology… he went to Google to try and impress on them, and so this is actually technology can be for good. So actually it’s the way we use it not it’s intrinsic nature. And also, brother, you know, the reason I used the word pernicious thinking back I wasn’t, you know, that word came up is because it also can lead to mission creep. And I’ve noticed in Plum Village over the years how the phone is, in a sense, slow, it’s bit like an invasive species. It sort of slowly takes over. So the other day I saw someone speaking on the phone in the tea house in Upper Hamlet, and I’ve never seen that before. And so it’s like our mind sort of can sometimes take an action and then that becomes normalized and then it takes another action. And one of the things I really like in Plum Village, during the summer retreat, is that with the teenagers, you actually take their phones away.

00:52:20

Yeah, that’s very intentional. You can’t join the program if you don’t give up your phone.

00:52:24

Because that you know that if they have their phones then they will not be present in Plum Village and you also know that when you take their phones away that they engage in a completely different way with each other, with their surroundings. And they can have their own transformation. And with the phone they wouldn’t experience that because the pull of it is so strong.

00:52:47

Yeah, and I really remember this moment in the summer retreat. We do these picnics with like everybody in the retreat so it’s like 800 people eating all together. And we’re in Son Ha residence, at the garden. And after walking meditation we enter into this garden and then the monastics surprise everyone with the musician Brother Spirit, Sister Trai Nghiem, and other musicians that are present in the retreat. They would play amazing music and then everybody’s like entering literally into like it seems like the Pure Land of the Buddha or like the Kingdom of Heaven. And I was sitting with this family next to me, for the picnic, and the mother, a young mother, turned to me. She said, Brother Phap Huu, it is incredible. Nobody is on their phone in this moment. And so what we can see there was this collective consciousness because everybody has the art of being. Everyone is enjoying togetherness, enjoying their children, enjoying the company of friends that they have just made in this retreat. So collective consciousness plays a very big part in this. And that’s why in these retreats, especially when we have business people or we have leaders in different sectors where they’re always engaged in action, whether it’s their laptop, their phone, we always encourage is an invitation to not use your phone in public spaces because that is a collective energy that we set right. But we say let us use our phones maybe a little bit more discreetly in our rooms that we’re sharing or even in the forest, so it doesn’t have a domino effect. Because suddenly you say if Jo is using it then I can use it. Right? So that’s why I was sharing, like if we can build a culture… And I feel it’s already gently happening here, but if we can collectively inform each other that we want to have a culture around the phone, I think that can play a big part in it. It’s almost like when the car was introduced, people didn’t fasten their seatbelt. And then slowly rules were implemented. And I feel like with the speed of the internet and the speed of social media and technology like almost like our ethical principles around them can’t catch up. And there’s not enough time for it. So I feel this, as a humanity, like this is also our responsibility. I feel that pointing the fingers doesn’t help. And I pointed the finger to myself, to my community. But it’s like how do we then shift culture around it? That is where I feel is important. And I just want to bring back to like the wisdom of Thay, like I remember in 2007, we had a day of mindfulness just for monastics. And laptops were like the new thing that it was becoming faster in the development of laptops, they were becoming thinner, they were becoming more accessible. So suddenly more monastics were having laptops and that’s not a part of our precepts. Right? That’s not a part of our mindful manners. That’s not a part of our policy. And we all come from different backgrounds, so monastics who come from a richer family or a family that was more well off, like their parents were donating them laptops. So, you know, it brought in like jealousy and all this. So like there is this whole thing about how to be with this new technology in the community. And then one monastic asked Thay in a Q &A in that day of mindfulness and the way of asking it was literally like it was shaming all of us, young ones. It was like Thay, like I’m not even like faking it. It had this tone. It was like Thay, these young monastics, they’re all, you know, being, they’re all falling into debate of consuming. So everyone’s having laptops. Thay, what is our policy around it? And hoping like, you know, Thay would, yes, you young monks and nuns, you’re all walking down the wrong path and like scolding us. Like, I know, right speech and right action and right mind, but I really feel like my sibling that was asking this question…

00:57:30

It had a barb in it.

00:57:32

It had definitely, it had two sides of the… It was sharp.

00:57:38

Yeah.

00:57:38

Right. And Thay, he said, Thay expects in 10 years we’re all going to have laptops. It’s going to be just like a notebook that we’re all going to have. So it’s not about the laptop. It is about how we use it. It is about what kind of practice do we build around it.

00:58:29

So brother, you talked about collective consciousness. And so some of the questions which were so pertinent is how can one be an individual in a toxic system? So I just want to read out there are just a couple of questions, short questions I’ll read out which give a sense of that. So the first is burnout and hustle culture is glorified in many companies and industries. How do you prioritize mindful living while not seeming lazy or unmotivated? And the second one, I feel I climb in and out of a state of burnout. How can I make long lasting change when in many ways our culture demands our constant attention? It feels like going against a strong current. And that’s such a… I mean both of those but that second one feels like going against a strong current. You know, it’s that sense of if you’re trying to swim in a river and the current is just dragging you away, you know, the power of that is so strong and the more sometimes you try and resist it the more tired you get from it. So it’s a difficult one and just before you come in, brother, it reminds me of, in my first sort of senior job, I was I think 26 years old and I was working at a newspaper in England called, the UK, called the Daily Telegraph. And I was the news editor of the business and finance section and I had no understanding of business and finance. I had got this job almost by mistake and I was really struggling with it because, you know, a newspaper, daily deadlines, all this news coming, it was very overwhelming. I was young and inexperienced. I was having to really work long hours just to keep my head above water. And there was one evening and it was about 8 p.m. and I was one of the last people in the office trying to sort out stuff for the second edition. And one of the sort of more sort of mature journalist came up to me and he said, Jo, you’re looking exhausted, your eyes are red. He said, I’m going to give you one piece of advice. He said, the cemeteries of England are full of people who thought they were indispensable. Now I suggest you go home. And that was such a powerful, I mean it resonates still so strongly because it was like, I was, I felt I was expected that I had no choice but to work those hours and that if I didn’t it would be the end of me and that everything relied on me. If I didn’t do it, who would do it? And just that sense of all the people who have lived this life who have passed away, who at the time thought they were indispensable, led a life that was often in sacrifice. But of course, if I had been left that job or been sacked from that job, someone else would have come and done that. You know, I’m not indispensable. And that was such a relief to me because we take so much on for ourselves that we think yes, there is a system that is pushing us to be a certain way. There is a system that makes demands of us, but actually within that system we always have agency. There is always something we can do. So brother, what was, how do you see it that when the system is so strong, how do we, in a sense, find our own path of happiness within that?

01:02:25

So there’s going to be layers to this answer. I want to start off with we used to have a much more simpler life. Even in my short span of living, only 36 years, I have seen the drastic shift in our ideal of success and enough, so we do more, we sacrifice more in order to have more, because that’s what we have been told, and that’s what we have seen maybe on movies, television shows, stories that have been handed down…

01:03:11

Advertisements.

01:03:12

Advertisements and so on. Right? And the first layer to my answer is our lives are short. What we can do in our lifetime can be an imprint for generations to see and learn. So how we choose to live our life fundamentally it still comes back to our own agency if we have that awareness that I see suffering, I see that this is toxic, this is making me a toxic person. This is destroying all my relationships. So in the eight noble path, then we can say that this is not a livelihood that is supporting our well-being and our deepest aspiration. And so, if we have that mindfulness, and if we recognize that this livelihood even though it is paying me very well, but it is destroying my heart, then what is… Is it worth it? I really want to ask this question and I’ve asked this question even in my monastic life. Right? And so the encouragement of mindfulness is I cannot tell you, but it is for you to use your own awareness to see do you have the ability to continue to be a happier person and have freedom in this career. And I know that that question also can be a luxury for many people, so I’m sharing this with this layer of understanding some of us we don’t have that option. Right? So that’s what my answers can be very layered. So for the first layer is like if we see that this is too toxic and I’m willing to have another job, another livelihood, another career that doesn’t pay me as much, and I can change my way of being. I may have less, but I have more of love in my heart, I have more of time to connect and becoming a more compassionate person. I regain my freedom. Then that is a worthy choice. So this is one layer. There is another layer of those that may be the ones that are creating the culture around the workforce. And if we see that this is a source of suffering that we are experiencing and we are may be a part of the system too, can we have the heart of a bodhisattva of being in the system and help changing from the inside. And I have this friend, she’s a long time practitioner and she is like, she’s like, Brother Phap Huu, I bleed Plum Village, but I got to be in the beast. She’s like, I got to meet capitalism at its front door every day, because if we want change, we can’t run away from it, we got to be in it. And I love that quote because she has freedom when she says that, she doesn’t say it from a space of anger or hatred. She’s a minority, as a race, in America, but she’s like, she understands that complaining about it is not enough. I need to be in it and I want to shift the culture in my little teams that I can work with. So there is also a bodhisattva vow that for those of us who can be in it and help and listen to the suffering and make that step to change the community. And I’ve seen that there are those who like you, Jo, Christiana Figueres, those who work in organizations who really want to shift that culture, that way of being, and they see that they have to change first. You have to change first. And then when you recognize that it can work like we can bring elements of this way of being into our workspace, it will shift. And then the third layer is those who of us who sometimes we know we can’t change the job that we’re doing. And it is about how can we find the non-toxic moment in these spaces. And how can we balance our other way of being, maybe not during the work time, to have enough stability, joy, and life. And then from that don’t stop there, and then from that, how do we carry that into the things that we are doing that we may not love? And this is where like you said, Jo, like sometimes the gift is not only in the pleasant but it’s in the unpleasant moments of the work that we do. And I practice this a lot. There’s a lot of moments I’m just like what the heck am I doing? Why do I have to do this? Why do I have to be here? And internally like I can listen to my mind, I can listen to my way of projecting. And I ask myself, can I change my way of being in this particular moment that’s so uncomfortable right now? And then you start to build up another muscle inside of you, your spiritual muscle of still dwelling happily in the present moment. And this is a quote that our ancestral teacher, the Buddha, has given us. And when it is said dwelling happily in the present moment it doesn’t mean that that moment needs to be happy for us to be happy. But it is about being happy no matter what. Even I miss the most unpleasant moment that that is really deep practice and that is a deep insight that we need to keep cultivating on a daily basis to arrive there. And it is possible, that I can share.

01:10:24

So brother, you bring up a lot about the second half of our book which is about healthy boundaries because this is a tender space, because Thay said, you know, if you’re in a toxic environment for too long, that is very hard for that not to turn you into a toxic person because you’re so immersed in that culture that it starts to be like technology, starts to seep into the system. And at the same time, just because we’re unhappy somewhere doesn’t mean that by moving we’re suddenly going to be happy. And I always remember in one of the questions on sessions actually in the main meditation hall someone said, you know, I’m really not enjoying my job, I don’t feel like it’s purposeful. I want to sort of leave my job and find something more purposeful. How do I do that? And the response I thought it really struck me that I was, yes, of course, you can find another job. But actually that job will probably… all the same issues in a different form. And there’s something about how do you work with what you’ve already got and what are the, what is the one or two things you could do that while you’re in that job you start to take back some agency and start to say actually who can I align with, who is an ally here, what is the one thing I can do that could potentially make a difference? And I also like that feeling I know a lot of people who work in systems changing, how do you change these complex systems? And it looks like you’re trying to move a mountain or headbutting and trying to knock down an immense wall. And what I like is the people who talk about finding the acupuncture points of change. That, you know, I occasionally go to acupuncture and sometimes one needle is all that’s needed to open up an entire system. And so there’s something about the mindfulness of being able to look at the system, any system you’re in, and saying actually I can’t change that system head on, but what is the one thing I could experiment with or do that would have a chance of leading to another action which then might lead to another action which may lead to another action that eventually may have the chance of changing that system? So sometimes a system can change from one small change that can build over time and can become the big change. And it speaks also to that idea which I love in Thay’s teachings and in Buddhism about ripening that actually if we take an action, if we have the agency and the support to take an action that we may, a year later move that job, move to another job, but actually that action may have started something rolling that even years later may start to really shift that culture. So it’s a very tender place to not get trapped in some way if you have a choice. And also, brother, I just want to come back just very briefly, and you’ve already spoken about it but I think maybe just to give it a little bit more space. So people who feel stuck, so there’s a question here. I wish I could come up with a good question but I am exhausted. And I think that, you know, just really feel for that person. I’m so burnt out at work and have compassion fatigue or vicarious trauma from my job. How do I survive when I desperately want to leave my line of work but cannot for financial reasons? And I know you’ve spoken about this, brother, with sensitivity and it’s just to sometimes with questions it’s just to deeply hear the question and know that that sort of cry has been deeply heard. You know, that it’s, that there are many people in the world who feel very trapped and don’t feel that they can create the change in their life that they want to. And I feel that the Plum Village practice is not always having to take an action for someone else but just to hear that. And just to say that in that question if we really spend time listening to that question and listening to the depths of that question just by holding that person in our thoughts, it’s not enough, but hopefully if we do that for each other when we’re in pain that we can really just be there for each other and listen to each other and not necessarily feel we can do something about it, but just sometimes to be heard is balm to the wounds of life. Brother, thank you so much. This has been a rich and deep conversation. And I love these recordings because I learn and I’m able to reflect, it’s like such a joy to be sitting with you and to have this space and time to explore life. And, dear listeners, we hope also that we’ve answered your questions in a way that supports you. And for those who didn’t ask a question that we’ve covered some of this. There’s so much to talk about that I think, brother, we’re going to have a second episode around this so that we can give the space and time to answer some more questions. And also, dear listeners, this is a celebratory moment because our first book has been published. It’s there, you can order it online or from your local bookseller, if you have one. And we really hope that it’s a companion. I think a lot of people speak about this podcast as being a companion, that wherever you are in the world, I had this week people from Ecuador, Argentina, other parts of the world come up and say, you know, there’s no local sangha, this podcast is a companion and a friend. And there’s also something lovely also about having a book and something physical. It’s a pocket book, you can slip it into your pocket and carry it around and that it supports you personally in your practice and your way of being in the world. If you buy it and enjoy it it would be wonderful if you could leave a review on one of the platforms whether it be Amazon or anyone else just so that other people can also find it and maybe also benefit from it. So Brother Phap Huu, thank you so much for your wonderful gift of the way you’re able to just, you know, I’m able to sit here and just… It’s like the sun actually. I started off talking about the sun. And the sun is like sometimes you sit outside in the sun and you just feel warmed by it and you just feel nurtured and loved by the warmth of the sun and I felt that very much today sitting with you and feeling warmed and supported and loved by you. So thank you.

01:17:58

Thank you, Jo. And thank you everyone for your questions. This is just part one. We’ll have another episode to answer more of the questions. And this is a topic that, as you can hear, is very alive for both Jo and I also.

01:18:12

All the best and see you soon.