By Cameron Conaway

The pain started just a few minutes into what I thought would be a calming five-day retreat.

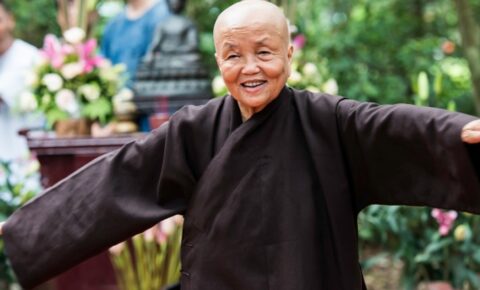

I’d been living in Bangkok for two years, and shortly after I arrived I began to hear of a man named Thích Nhất Hạnh. He was a Zen Master from Vietnam and, in many circles, Thây, as he’s often called, was seen as the world’s truest master of peace — like the Dalai Lama but with more focus on practice and less on celebrity.

Lessons generally come to me the hard way, something like Wolff’s Law of Bone Adaptation — how a bone put under stress can eventually lead to a stronger bone. As a poet, I’ve had my work and sometimes the ideas behind it questioned, dissected and at times torn apart by poets like Lee Peterson, Richard Siken and Alison Hawthorne Deming. But this was always only the first part of the process. The next, the crucial part, was how they always created the supportive structure to heal and rebuild until the poem found its legs.

Perhaps nowhere in my life was this “hard” learning more evident than in my career as a mixed martial artist. I’ve been choked, slammed, punched and kicked by fighters like Renzo Gracie, Mac Danzig and Eddie Bravo all for the sake of learning how to choke, slam, punch and kick and to learn how not to get choked, slammed, punched and kicked.

So when I got word that Thây would be leading a retreat in Ayutthaya, a short train ride from Bangkok, I knew I had to be there. I mean, back in 1967 Martin Luther King Jr. nominated Thây for the Nobel Peace Prize for goodness sakes, and his practical lessons on mindfulness now put his followers in the tens of millions. Surely he has plenty of lessons to teach.

And the first one crept deep into the muscles of my back during the opening 20 minutes of sitting meditation. I hung with him during Round One as he guided us through and asked us to envision our father as a curious, young boy playing in an open field. Man that was powerful, especially considering my personal issues. But Round Two I can barely remember because of the discomfort. Pain now worked into my hip flexors and my neck. To say nothing of the other kinds of struggle, of not having immediate distractions for example — no smartphone or television, no books or work to do but for the hard labor of being absolutely present to the cadence of my breath, to the way thoughts rolled into me like a gentle fog, to the wisdom of Thây’s style of working out by working in.

Before we stood up he told us how to walk. How to walk? I think I’ve got that down, Thây…

Every step should be a kiss to Mother Earth. Think of what a miracle these legs are. They allow us to travel freely and in collaboration with our eyes we’re able to see a paradise of forms and colors that make this beautiful world. Some do not have legs. Some do not have eyes. Some do not have freedom. Walk mindfully. Peace is every step.

I felt my toes sink into the carpet, the miniscule muscles in my feet and ankles root me to the floor. Through breaking down our functional fixedness, our distractions and even some of our bodies, Thây built us back up. We were in awe of our bodies, observant of the wonder that is walking.

4:30 a.m. Waking meditation. Walking meditation. Sitting meditation. My mind drifts: Is it almost time to eat? BOOM. He begins to tell us how to eat. Oh c’mon, dude…

Every sliver of carrot needed the sun, the water, the air, the care of another human being. Imagine the effort to grow that carrot, take it from the earth, pack it, cut it and get it here for you. Pay tribute to that. Chew mindfully. At times, close your eyes and pay homage to the carrot. Think of the nourishment it needed to be and the nourishment it’s providing as a gift for your body.

During breakfast I looked around to see many people chewing with their eyes closed, sensing the food and the story that brought it here. Athletics are so often about choosing healthy foods, pounding them quickly and moving on. Bringing mindfulness to each bite beat me down just as much as when that roundhouse kick landed flush against my nose, just as much as when the essay I was so proud of came back covered in red ink.

Days passed. The stabilizer muscles in my back strengthened. The ole’ hip flexors adapted.

On the final day of meditation, for the first time since I entered the cage and touched gloves with my opponent, I felt enraptured by nothingness. And when I stood up I felt the beauty of moving, of the gentle buzz of our collective moving, of my body, of our collective bodies.

And when I ate I…

And when I rode the train home I…

Thank you, Thây, for giving me a swift kick into mindfulness.

Share Your Reflections