Brother Phap Dung outlines Thầy’s aspiration and vision for residential spiritual communities as a service and refuge for society.

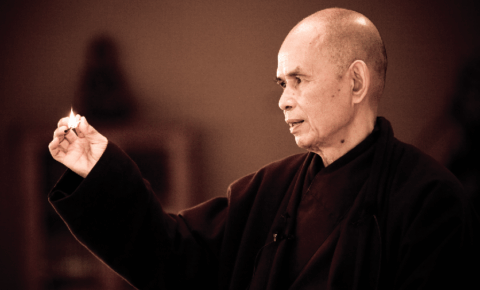

Sangha building is the most noble task.

— Thich Nhat Hanh

Dear Friends on the Path,

Lately, the word village has been occupying my thoughts, prompted by our dear teacher’s use of this word in the name Plum Village, our first practice center in the West that he established. He used village rather than opting for words like monastery, temple, or meditation center. Many well-known Vietnamese monasteries, such as Thiền Viện Trúc Lâm (Bamboo Forest Meditation Center) or Chùa Từ Hiếu (Compassionate Filial Piety Temple), carry these traditional terms in their names.

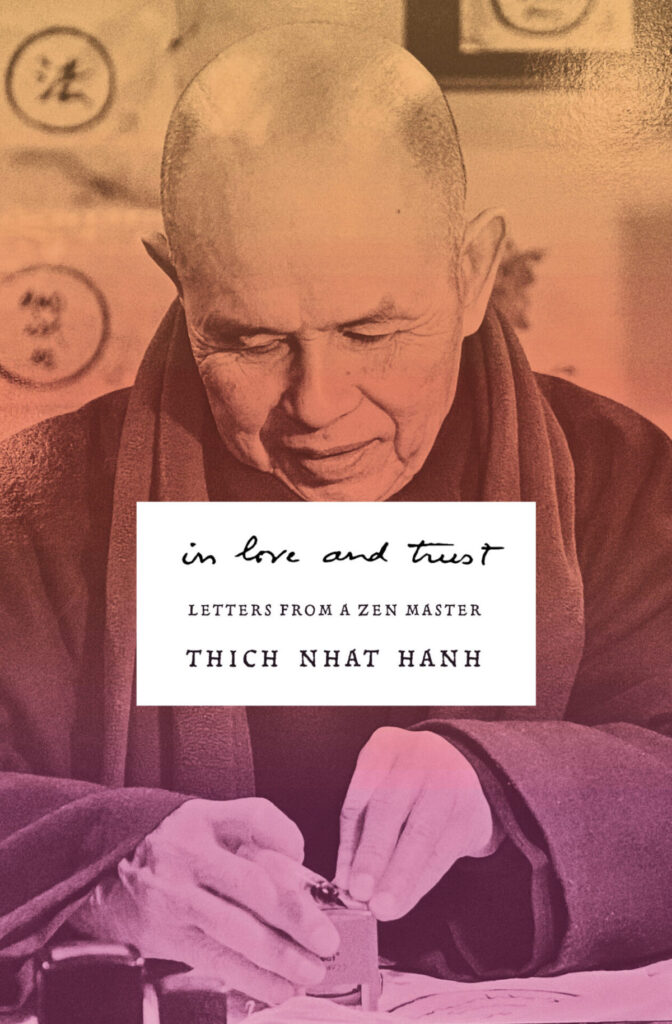

By the time I was ordained in Plum Village in 1998, Thầy was already well known in the West, and Plum Village had become a popular mindfulness practice center, no longer just a gathering place for Vietnamese refugees. Plum Village was all that I knew, and I took its name for granted, not giving it much thought. That was until recently, when I read a letter titled Non-Action, written by our teacher in 1973 to Brother Chau Toan, his younger monastic brother, in which Thầy reflected on the village cooperatives established by the Jewish people in Israel in the early twentieth century. This letter was part of a collection of letters recently compiled and published as In Love and Trust by Parallax Press.

In this letter, Thầy draws insights from Jewish cooperative communities (the moshav ovdim and kibbutz) he learned about in Israel, envisioning a village model rooted in mindful spiritual living, mutual support and kinship, and sustainable ethical livelihood. He also distinguishes his vision for these new communities from past socialist cooperatives by emphasizing that they will be formed through volunteerism and will include a spiritual component.

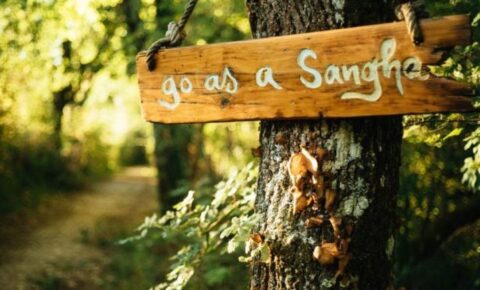

I am convinced that when our beloved teacher Thầy established our community, he intentionally chose the name Plum Village to reflect his deep aspiration—carried since the war in Vietnam—to create a refuge center far more expansive than a temple or monastery, a progressive model for social development. After the war and his exile from Vietnam, Thầy established Plum Village in the West to embody his vision of a living, dynamic community, where the monastery is just one essential but integrated element of a larger societal vision. This vision, which I call the village way, or làng quêin Vietnamese, aims to build a community that goes beyond traditional religious structures, offering a holistic model for living mindfully and spiritually, close to nature, with mutual support and collective responsibility. I believe his vision was to model the traditional village life in Vietnam, which is evident in his use of the word hamlet, or xóm in Vietnamese, to describe the different communities within Plum Village, such as Xóm Mới (New Hamlet) and Xóm Thượng (Upper Hamlet). These terms, xóm and làng, are rooted in Vietnamese village culture, where they describe the various neighborhoods that make up an interconnected community. Làng means village, or thôn in Sino-Vietnamese, as in Mai Thôn (Plum Village’s formal name), where mai means plum. Quê means countryside and connotes a simple rural lifestyle that is deeply connected to the land, community, and nature. Làng quê is an endearing term that evokes a life of simplicity, interconnection, care, and mutual accountability.

This article seeks to extend Thầy’s message, reflecting on and exploring this notion of the village way, làng quê, and offering, in the end, an invitation to all our sanghas to consider the possibility of forming residential communities as the next level in realizing our teacher’s vision.

Brief background and inspiration

I have always felt empowered and inspired when hearing Thầy, in many of his talks, describe our sanghas as communities of resistance. He saw the sangha as a collective force that resists not only external negativity and the gloomy narratives of modern society but also the internal obstacles that cloud our perception of life’s wonders. Thầy recognized that the world often promotes fear, anger, separation, and consumerism, which blind us to the interconnectedness and beauty of existence and our human species. By cultivating mindfulness, compassion, and collective care, the sangha resists these forces, creating an environment where the wonders of life—love, joy, peace—can be recognized, nurtured, and shared. This resistance is not against people, but against the harmful mental patterns and societal structures that perpetuate suffering, disconnection, hate, and division. He encouraged us to form sanghas and establish practice centers that embody the very spirit of the village way, which he called Communities of Mindful Living.

I feel Thầy’s earliest vision for social change remains as deeply relevant today as it was during the war. As technology and urbanization accelerate, many of us experience growing loneliness, isolation, and despair. Modern society often separates us from ourselves, each other, and Mother Earth, leaving behind a spiritual vacuum, especially in this digital age of gadgets, smartphones, and social media. The mental health of our families and society is inextricably linked to how we have organized our cities, neighborhoods, and communities, as well as to the individualist mindset our culture has long promoted. Neighbors not knowing each other has become the norm; “your side of the lawn is your business, not mine” is a widespread attitude. Meanwhile, the popular media’s agenda continues to fuel division, suspicion, and hatred. It will truly take a village to resist this culture of hopelessness and despair.

Thầy foresaw these challenges and offered a practical, compassionate response rooted in communal living and spiritual practice. As meditation and mindfulness grew in popularity, Thầy emphasized the essential role of the Sangha, which he regarded as equally important as the other two jewels—the Buddha and the Dharma. He continued to lead large retreats, to offer people a direct experience of this village sense of togetherness, despite facing disapproval for such large gatherings. Thầy understood the power of the collective energy for healing and transformation, recognizing the interbeing nature of the individual and the collective. He consistently invited us to embrace the noble task of building the beloved community, a vision shared by Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Thầy proclaimed that the twentieth century’s emphasis on consumerist individualism must now give way to the twenty-first century’s call for communities of interbeing—or communities of mindful resistance—if we are to survive as a species. “Sangha building is the most noble task,” he often encouraged us.1

Thầy’s dedication to building community and reviving the Vietnamese village way is not an abstract ideal or romantic nostalgia—it is a practical, embodied model for our times, one that was urgently needed for a country [Vietnam] suffering from the destruction of war. We can only imagine that in times of war, there was no room for ideological dreams—only applicable, real-world solutions that could bring real hope and purpose to the Vietnamese people being tormented. The term làng quê suggests a deep love for the simple countryside values, the tender togetherness spirit of the village collective. This revival does not signal a sentimental return to a pre-modern agricultural past, but rather offers a clear and relevant response to today’s most pressing crises: loneliness, despair, separation, fear, hatred, and climate anxiety.

The village way blends spiritual practices of liberation and collective responsibility with active social engagement and exemplary ethical living. It is the hidden mycelia network that holds the spirit of the village community together. This spirit invites us not only to dream of a better society but also to build it with our hands and hearts, becoming the change we wish to see in the world—a healthy, sane, and compassionate society. In this way, the village or sangha becomes a living Dharma body—a tangible expression of the path of awakening, embodying our Buddha nature—guiding us toward a more mindful, resilient, and inclusive way of life. As Thầy proposed, the next Buddha will not be an individual but will be a community living and practicing together in harmony and awareness.

photo courtesy of the Deer Park monastic sangha

1 Thích Nhất Hạnh, “True Transmission,” The Mindfulness Bell 81 (2019): 6-15.

Read Brother Phap Dung’s full article here: Thích Nhất Hạnh’s Vision: The Village Way as the Beloved Community of Engaged Buddhism.

In Love and Trust: Letters from a Zen Master — out now from Parallax Press or wherever books are sold.

Share Your Reflections