Sister Tam Muoi (aka Sr. Samadhi) recounts her personal journey with the practice of White Awareness.

White people, do something. But what? Please allow me to share some of the journey I’ve been on for the past five years, initially with the aspiration to create more diversity in our Sangha, but soon realizing that there was a whole other journey to come first, the practice of White Awareness.“White” as a description for people, entered the European languages in the late 17th century, used in legal documents to differentiate slave owners from the enslaved https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_people#A_social_category_formed_by_colonialism

I Woke Up

At Deer Park in 2015, during the American teaching tour, I participated in a workshop entitled “Racial Equity.” The workshop was offered by a coalition of Black, Indigenous and People of Color and White monastics, lay Dharma teachers, and OI members. I was on board, and completely with the White practitioner who asked the panel, “What can we do?”

The answer has stayed with me, like a koan, “Don’t ask us, People of Color, to educate White people about racism and diversity, along with everything else we are doing. What you need to do is educate yourselves!” Thus I began my journey.

Are You Sure?

Before the workshop in 2014, I had the great fortune to be among the monastics whom Thay (Thich Nhat Hanh) sent to live at Blue Cliff Monastery, our center in upstate New York. I lived at Blue Cliff for three years and among many benefits, I had an entirely different experience of race than I was accustomed to in rural England, where I grew up, or in southwest France at Plum Village.

My first retreat at Blue Cliff was a weekend Lawyers’ Retreat. I was intrigued and expected the monastery to be full of White, wealthy men. But no! Our abbess, Sr. The Nghiem, dedicates her efforts to inclusion in all forms. As a result, Blue Cliff enjoys a continuing friendship with CUNY Law school, the top school for social justice in the US. Its stated mission is, “to transform the teaching, learning, and practice of law to include those it has excluded, marginalized and oppressed.”

On Friday afternoon at the start of the Lawyer’s Retreat, a bus turned up. It carried a multitude of engaged and inspiring young people, and their professors, representing the ethnic diversity of New York City and its boroughs. I noticed my preconceived notions about lawyers starting to shift.

That evening, to my great shame, I asked a mature African American woman sitting next to me in the dining room. Was she a student? No, she answered, with a natural smile, I am the Chief Family Court Judge for the five New York boroughs. Now that’s the kind of discomfort that this journey has brought me into time and again, but I am learning how to stay with it, to feel it in my body, and above all, to learn from it, and be humble.

Later, I had the chance to go to a “Zen and Race” training in New York City, given by the first African American Dharma teacher, Merle Kodo Boyd, from the Zen Peacemaker Circle. My most vivid memory of that ethnically diverse weekend was learning for the first time the phrase “micro-aggression” and what it means.Microaggression: brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative prejudicial slights and insults toward any group, particularly culturally marginalized groups. [source: Wikipedia]

Whilst sharing in a dyad my partner shared how, often at public events, his wife, Latina by origin, is frequently addressed as if she were one of the catering staff. The assumption about his wife’s occupation because of her skin color brought it up again, discomfort. What to do with that knot in the stomach, the dry mouth, the anger I felt, and the helplessness?

Getting Curious

By the time the annual People of Color (POC) retreat came around, I had learned enough to understand that POC retreatants need their own space for safety and confidentiality, free from the additional burden of worrying about White people’s feelings. Nevertheless, this was the first time I witnessed the harmful effects of “color blindness”Colorblind” is a common defense that White people use when faced with racial discomfort e.g., “I don’t see color. Aren’t we all the same? from those of us who were not yet aware of White privilege. I observed the expression of strong feelings, including annoyance, sadness, and anger at not being able to join the POC Dharma sharing groups. Many White participants expressed well-intentioned reasons for wanting to join in, such as, “We want to learn, we want to hear the POC experience first-hand, and we want to help.” Another was, “Blue Cliff monastery is our home, and I feel frustrated if I’m not allowed to join in the sessions.”

Breathing in, I say hello to my irritation, breathing out, I notice the discomfort in my body. What to do? Understandably, in our tradition, we know that compassion arises from listening to suffering and being aware of suffering; and many White members in our sangha wanted the opportunity to bear witness and listen to the suffering of our POC brothers and sisters, so they can better understand, in order to help. I heard the anguish of the White participants who felt excluded. But I also want to be aware of slipping into “entitled” mode, which goes hand in hand with White Privilege. However, I have learned from many POC activists that it is not enough to have good intentions for our actions, we must be aware of their effect.

For instance, by wanting to join the POC dharma sharing, the effect of my well-meaning is to disturb the safety of those in the group. One of my privileges as a White person is that I can meet my needs for safety without question. Still, I feel determined to use my privilege to help, which means knowing when to withdraw and respect others’ needs, which can be different from mine and may exclude me.

Deep Looking

In 2016, another experience raised my awareness of what it means to be White. I visited the newly-opened African American museum in Washington, DC. I will never be the same again. The visit starts in the basement, with the history of slavery. What did I find in those glass cases? I found my own country, England. I found the British Royal family, owners of the monopoly on transatlantic slave trading for a century, starting in 1660. Competing European nations continued to practice the lucrative trade for another century. I found the names of many familiar English towns and cities, enriched from this trade in stolen and brutalized lives. I read how profits from the slave trade financed the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century and provided the capital to launch the British Empire.

I felt sick to my stomach. I felt angry, and a deep sense of betrayal that I had not been taught this in school. I felt anger towards my parents, who have always held a high opinion of the British Empire. This wave of feelings went way beyond discomfort. I was stunned.

In Washington DC, I met head-on the shadow side of my land ancestors. I learned of their greed, which had driven them. Because of our practice, I know that I too have the same seeds of greed in me coming from the fear of not having enough. Nevertheless, that day in the museum I began the lifelong process of unpacking my heritage of suffering and exploitation and seeing with new eyes the history that gives me White privilege today

Later, with more reading and discussions with other friends on the path, I wondered to what extent had I already known these facts. Had I been in denial, keeping myself ignorant because I enjoyed my privilege? Why had I not been asking the right questions? So, I stopped blaming others and started to see my responsibility, which was the beginning of empowerment to change.

At first, privilege seems too strong a word. I am not rich, titled, or landowning. However, while reading Peggy McIntosh’s “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” I realized the extent of how I benefit from an “invisible system conferring dominance on my group.”

For instance, McIntosh offers 50 examples of daily privilege that most White people assume without question. These include:

- I can go shopping alone most of the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed.

- I do not have to educate my children to be aware of systemic racism for their own daily physical protection.

- I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.

- I can arrange my activities so that I will never have to experience feelings of rejection owing to my race.

With more unpacking, came the heartbreak, the shame and the guilt. But looking deeply I realized that to be an effective ally for POC friends, they do not need another white person overwhelmed and stuck in guilt. I remembered Thay’s teaching to a US veteran who had killed four Vietnamese children during the war. Rather than be overwhelmed and paralysed by his shame, he could now save thousands of children by becoming an activist for social justice. Knowing that silence is complicity, I feel determined to practice.

First by developing compassion for myself, and then for my parents who were conditioned by their education and society in the 1930’s. I take care of my strong feelings by recognising the seeds of violence, greed and fear in me, and embracing them tenderly as a mother would her crying child.

Transforming the Seeds

Now back in France, I continue this work of unpacking race with a group of Plum Village practitioners, lay and monastic. We took the initiative to start an online White Awareness study group. We come from France, Holland, Germany, Sweden, New Zealand, and England. We create a safe space in our monthly Zoom calls, for sharing, listening with compassion, holding our painful feelings. We practice with love and understanding to transform, using our determination and aspiration for change.

Some feel dismayed by a need to create a separate space for White people to do this work. Ruth King, an African American Dharma teacher and author of “Mindful of Race,” offers insight and guidance:

“In a racial affinity group, White people can…cultivate racial solidarity, compassion, and support each other in sitting with the discomfort, confusion, and numbness that often accompany White racial awakening. They can also discern White privilege and its impact without the aid of or dependence on POC.”

The Next Buddha May Be a Sangha

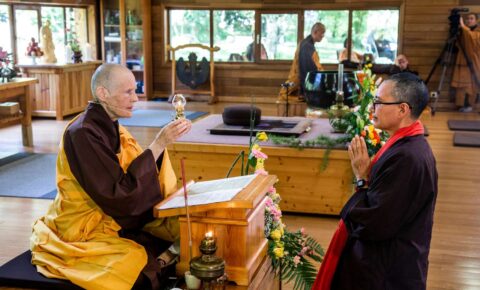

In February 2020, after nearly two years of study, we organized a pilot mini-retreat at the Healing Source Monastery. The facilitator was a professional anti-racism trainer, who also practices in the Plum Village tradition. During this powerful retreat, the facilitator guided us through exercises that brought to awareness how each of us has been conditioned from a very young age to discriminate against people of color. I remembered the cowboy films that my Dad loved to watch on TV, genocide of Native American people as entertainment? I recalled the “Black and White Minstrel Show,” a weekly TV musical production that the whole family watched. The show featured White men in blackface portraying African American men as childlike and simple. My childhood was full of nursery rhymes and children’s books containing offensive and demeaning words and images. And much, much more.

Gradually, I realized how slavery and colonialism were possible. By seeing POC as different, outside the historically White circle of morality, non-white bodies could be exploited and brutalized without remorse. Tragically, this pattern endured for centuries and continues today as seeds handed down from ancestors. As White people, we still have a strong habit of seeing ourselves and our culture as “the norm” whilst the global majority are “the other.”

With our practice of mindfulness, we can break this cycle of “othering” rooted in discrimination and wrong perceptions. Only if we can wake up to our deeply ingrained habits and conditioning, can we act with freedom from the best place in our hearts. To do this, we must first recognize the discomfort in our bodies, as it comes up. We embrace it tenderly, accept the feelings, and gradually develop resilience towards them, understanding that this discomfort is the mud in which the lotus will grow.

Now when discomfort comes up, I see it as an invitation for me to be courageous. I can ask the question, “Was that an unskilful thing I said?” I can respond thoughtfully by considering the other person’s need and then apologizing, listening, or giving space. I can serve as an ally to people of color and share with other people the practice of White awareness.

By the end of the retreat, we felt raw, vulnerable, deconstructed, but hopeful. Going as a Sangha, we support and encourage each other, continuing the work together.

This practice is also informing my monastic life helping me to build harmony across nationalities but also respecting my need for cultural sanctuary. Following in the footsteps of our teacher, Thay, we know that our path is one of contemplation and action. He teaches us to be courageous, creative, and to go as a river. Like a river, White awareness is not a state that can be achieved, but a path of practice.

Resources:

Resources for further reading, study, and discussion, ideally in a White Awareness group are here. Further, here is a list of 75 anti-racist actions and more suggestions for action as parents, educators, business people, administrators, sangha members, and as human beings. Although these ideas are U.S.-oriented, many can be applied to our situation in Europe and be used to open up conversations. If the resource lists feel overwhelming, take the White identity stage quiz and receive an individualized list of recommendations appropriate for different levels of awareness.

Share Your Reflections